Circulating the STS Hub 2023

STEFAN JOHN

How is STS, as a scholarly discipline, practised in Germany? Which are the approaches to STS here? How do these relate to each other and which topics stimulate joint interdisciplinary and integrated STS research? Which institutions and actors participate in German STS research communities? The new STS-Hub conference series, hosted for the first time by RWTH Aachen University on March 15th-17th 2023 tackled these questions. This event is the result of several years of talks, organization and planning led by, amon others, c:o/re director Stefan Böschen and Ingmar Lippert, whom we cordially welcomed as a short-term c:o/re fellow. The STS Hub is envisioned to move between established and emerging places for STS in Germany and to have a bi-yearly rhythm in-between the EASST Conferences. Financially, the event was institutionally assisted and sponsored by the BMBF, HumTec, c:o/re and several STS networks and clubs such as stsing, INSIST, the science and technology research section at the DGS and the politics, science and technology working group at DVPW.

Stefan John

Stefan John is a PhD researcher with the Living Labs Incubator (LLI) located at the Human Technology Center within RWTH Aachen University. His academic work focuses on (power) structures in Living Labs and the modes and understanding of experimentation of (knowledge) infrastructures in contemporary knowledge societies. He is also responsible with supporting the networking and research of LLI. Also, he is currently supporting the c:o/re events team.

Taking all possible roles as part of the local organizing team, panel organizer and panelist, I take the pleasure to briefly convey my experience of the conference and its theme, with a focus on the very insightful keynotes by Ulrike Felt and Susann Wagenknecht.

RWTH Aachen offered the Central Auditorium for Research and Learning (C.A.R.L.) as the main venue for the STS Hub.

Before starting the conference and welcoming all guests, INSIST took the chance to make an early career researcher barcamp, discussing the specific needs and problems of this status group and bringing them together. The barcamp format enabled the organisers to allow topics to emerge from direct inputs. To set off, Stefan Böschen and Torsten Voigt, the Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, took the stage and warmly welcomed the over-300 participants. Following Ingmar Lippert’s short overview of the idea of the STS Hub and its history, STS activities being undertaken at RWTH Aachen were presented in all their varied nuances. Different institutes, chairs and projects, such as the chair of Sociology of Technology and Organization (STO), the chair for Personnel and Organizational Psychology, the Computational Science Studies Lab (CSS), led by Gabriele Gramelsberger, the Human Technology Center, the embedded STS work at the WIRKsam project led by Andrea Altepost and, last but not least, the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, as a whole.

After a short break the first of six session blocks started, each lasting for two hours. A broad variety of topics were discussed in over 65 panels. These stretched from experimental democracy and political views to science and technology, to topic driven panels, e.g. on waste and software studies. The event also comprised experimental formats, such as fishbowl discussions and walkshops, and interdisciplinary topics to foster the circulation of STS ideas with other fields like art and educational studies. Discussions tended to relate, to various degrees, to an interest on the circulation of either knowledge, methods or topics. The theme of circulation is at the very heart of STS research, as particularly evidenced by topics such as the production and utilization of knowledge and expertise, import and dissemination of new technologies and innovation models, e.g. the Zimbabwe Bush Pump or the MIT model of innovation. Circulation stands in proximity to other familiar STS concepts such as infrastructure, translation and power. The Covid-19 pandemic gave prime examples of the circulation of a virus, (un)scientific knowledge, policies and infrastructures in all their contingencies. This virality is entangled with a set of political and normative groundworks, conference program explains that “circulations are never innocent – they can come at high costs for some while benefitting others. Costs and profits often emerge from the intertwinement of different systems of circulation. The circulation of socioeconomic value is contingent on the material circulation of waste in oceans as well as knowledge about their contamination. To circulate or not to circulate evokes questions of solidarity and of violence. Is there a responsibility of STS to resist, disrupt, or prevent some forms of circulation? Which circulations do we care for maintaining?” Another salient theme that emerged from the several panels is that of testing, which involves considerations on experimenting and infrastructures. The keynotes also pondered on this matter.

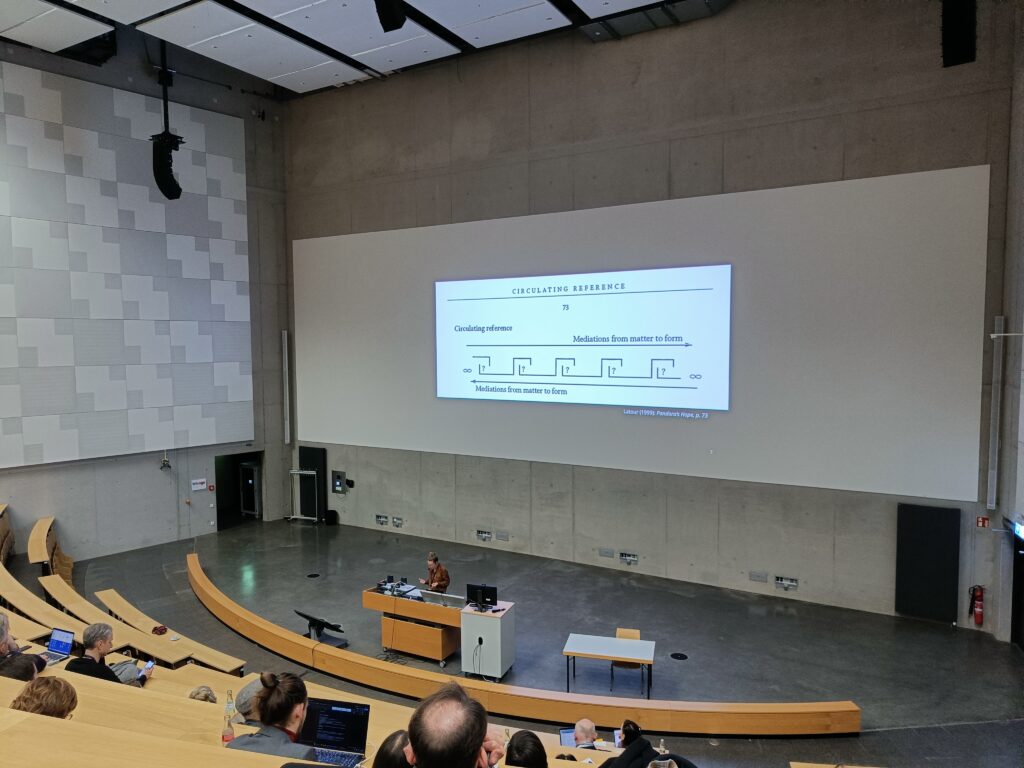

The first keynote, by Ulrike Felt, took a reflexive stance towards the tacit governance of contemporary academic knowing spaces. In her talk, “Infrastructuring Circulations”, she noted two coexisting logics at work in academic environments, namely “a deeply rooted logic of circulation” that encounters an increasing presence of a “logic of infrastructuring”. Reinforcing each other and creating friction (Tsing 2005), they create unique and specific arrangements of research cultures and power. The first conference day ended with a reception for more informal circulations.

Another, this time Latourian, take on circulation was presented by Susann Wagenknecht. Closely dissecting leakages in circulation allows for analysis of the transformation, materiality and morality of circulation. Wagenknecht illustrated this through examples of circular economies and handling of leaks.

Additionally to discussions on content, the STS Hub also served as a platform to talk about the current state of academia. In the Open Forum #WeDoSTS, Fanny Oehme as Ombudsman, Dr. Claudia Gertraud Schwarz-Plaschg and Dr. Daniel Müller were invited to give accounts on power within STS and the academic system as a whole. As activists against discrimination in general and, more specifically, sexism and abuse of power, they presented the prevalent problems, ways to address them and networks to aid in these situations. After this panel, to open up the debate and offer specific insights, small group discussions were offered by the experts.

The first STS Hub offered an excellent platform for discussion and exchange across hierarchies, new ways of portraying topics in STS through experimental panel formats and an overall welcoming atmosphere for academic collaboration. I would like to wholeheartedly thank Stefan Böschen, Ingmar Lippert and Mareike Smolka for making this Hub possible. We are looking forward to the next one!

For more information and detailed insights on the STS Hub, kindly see the review by Smolka et. al (2023).

Acknowledgements

STS-hub.de 2023 was made possible with the institutional and financial support of Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, stsing – Doing STS in and through Germany, GWTF – Gesellschaft für Wissenschafts- und Technikforschung e.V., INSIST – Interdisciplinary Network for Studies Investigating Science and Technology, Sektion Wissenschafts- und Technikforschung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie, Arbeitskreis Politik, Wissenschaft und Technik der Deutschen Vereinigung für Politikwissenschaft, Human Technology Center at RWTH Aachen University, Käte Hamburger Kolleg Aachen Cultures of Research, and RWTH Aachen University. Further support was provided by Kommission Wissenschaftsforschung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaften, the professorship for Wissenschafts- und Techniksoziologie at TU Dortmund, and the Team Innovativ Beratung UG.

References

Smolka, M., Braun, M., Gruebel, C., Neudert P., Rentrop, C., Wiedemann, L. Being, doing, and using STS in Germany? Reflections on identity questions, normative commitments, and conceptual work after STS-hub.de 2023. EASST Review 42(1).

Tsing, A. L. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

SFU Workshop on Transdisciplinary Pathways in Educational Research: Learning, ecology, media and beyond

On April 25th c:ore team member Alin Olteanu will be joining Natasa Lackovic (Lancaster University) and Cary Campbell (Simon Fraser University) for an online workshop, organized by the Research Hub @ Faculty of Education of Simon Fraser University, on Transdisciplinary Pathways in Educational Research: Learning, ecology, media and beyond. To attend, please register through the Simon Fraser University website, where you can also find more information. The description of the workshop is also below.

Transdisciplinary Pathways in Educational Research: Learning, ecology, media and beyond

The potential of transdisciplinary research and education has been lauded and discussed for decades. Despite often lofty promises, many have remarked on the lack of meaningful transdisciplinary research and teaching—ironically in universities, where it is most expected. Very little research presents or explores conceptual-philosophical frameworks (or pathways) for how to study and engage in transdisciplinary inquiry and questioning. Our workshop aims to address this theory gap, building from our team’s research expertise in educational semiotics and uniting theoretical perspectives from bio-semiotics, multimodality, and new socio-materiality studies.

Participants and presenters will collaboratively articulate transdisciplinary problems by distinguishing transdisciplinary methodologies and theoretical frameworks from related inter- and cross-disciplinary approaches. We specifically address transdisciplinary challenges associated with climate crisis (the Anthropocene) and the rapid proliferation of digital-media technologies, focusing on the continuity of environmental and embodied learning and digital media-learning.

“The simple is complex”: Professor Giora Hon starts the c:o/re 2023 lecture series on Complexity

On April 12, 2023, the 5th c:o/re lecture series started off. After c:o/re director Gabriele Gramelsberger welcomed attendees and introduced the speaker, Professor Giora Hon delivered his talk, From Reciprocity of Formulation to Symbolic Language: A Source of Complexity in Scientific Knowledge

Professor Hon introduced his notion of epistemic complexity, which refers to what may be considered simple, rather than complex. The talk was directed at clarifying the oxymoron “the simple is complex”. Professor Hon does so in light of three developments in the history of physics:

- the analogy between heat and electricity, following William Thomson

- the reciprocity of text and symbolic formulation, following James C. Maxwell

- liberating symbolic formulation from theory, following Heinrich Hertz

Professor Hon argued that, following this trajectory of ideas in history of physics, in Hertz the complete separation of formal theory and equations can be observed.

Entanglements of the concrete and the abstract @c:or/e: International Conference “Wissenschaften des Konkreten”

How does the relationship between concretion and abstraction manifests? How does focusing on the relationship between abstraction and concretion open up new perspectives on the history of natural sciences and empiricization? What methods are employed in collecting and presenting concrete objects from nature and science, and how are they reflected? What are the opportunities and limits of transferring the concept of ‘epistemic objects’ from the history of knowledge to literary and art studies? Can we identify coevolving styles of writing about the concrete in the sciences and in the arts?

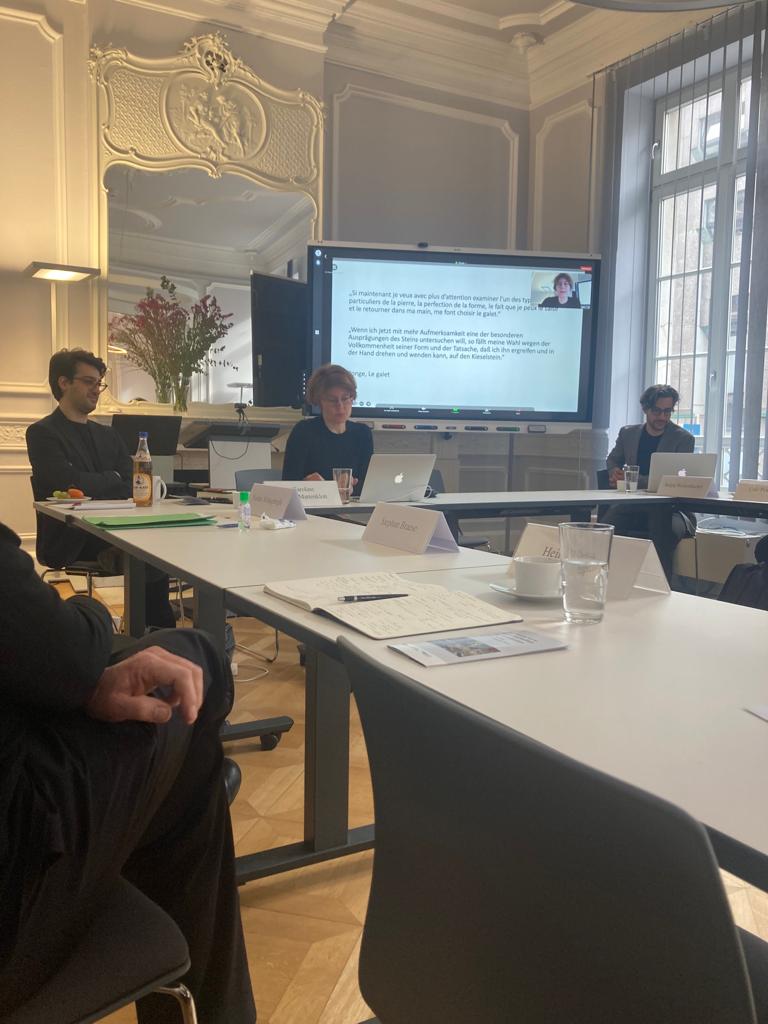

From February 15th to 17th, 2023, the Käte Hamburger Kolleg at RWTH Aachen University hosted the international conference “Wissenschaften des Konkreten”, conceived and organized by Caroline Torra-Mattenklott, Christiane Frey, Yashar Mohagheghi, and Sergej Rickenbacher of the Institut für Germanistische und Allgemeine Literaturwissenschaft at RWTH Aachen University. The concept of the conference is inspired, as its title shows, by Claude Lévi-Strauss’ “sciences of the concrete” (Lévi-Strauss 1997). Lévi-Strauss argues that both the ‘savage mind’ of the nature-based cultures* as well as modern science in industrialized societies emerge from sensual and experimental interaction with surrounding things. Over the three days of the conference, the participants explored the above questions and others from three different perspectives:

The first day of the conference opened with the perspective of “Abstraction and Concretion in the Arts and Sciences”. The speakers from the history of science, archaeology, and literary studies shed light on the interplay between abstraction and concretion in their respective presentations not only from the point of view of different disciplines, but also with a focus on different epochs (Lectures: Staffan Müller-Wille, Dietrich Boschung, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Udo Friedrich). On the second day, under the heading “Epistemic Practices between Sciences and Arts”, the emphasis was initially on a sensory perspective, with lectures on “Augenmaß” (sense of proportion), visual acuity and tact (Lectures: Christian Metz, Katja Haustein, Jonas Cantarella, Regine Strätling, Svetlana Chernyshova). Finally, the third day was devoted to “Concrete Details: Objects and Cases between Art and Science”. The presentations addressed rhetorical techniques of concretization as well as the relationship between people and their objects in literature (Lectures: Dirk Werle, Alexander Kling, Dorothee Kimmich).

Over the course of the three days, the conference took place in the charming premises of the Käte Hamburger Kolleg. However, the hybrid format also allowed international speakers and attendees to contribute via Zoom and participate in the inspiring discussions. A stimulating atmosphere of discussion developed allowing a common denominator to emerge despite the different emphases. It was repeatedly shown that the operations of concretion and abstraction seem to be inextricably intertwined. This relationship can be observed equally, for example, in Linné’s taxonomies, biogenetic research, and early modern rhetoric. Various techniques were discussed on the occasion of the lectures that mediate between the concrete and the abstract, including graphic schemata, the sensual-habitual “Augenmaß” and rhetorical procedures. The concrete has proven itself to be multifaceted. Sometimes it manifested itself as the concreteness of scientific working methods or as rhetorical-linguistic detailing or through its reference to objects.

In the lively concluding discussion, it became clear that there were significant similarities in concretization techniques across disciplines and epochs. Abstraction and concretion were understood not only as linear procedures building on each other, but as dialectical processes in which objects, research subjects, and artworks can shift from one state to another. For this reason, a temporality is always inherent in the concrete. Furthermore, the basic sensual-intellectual action with the concrete, which precedes every abstraction, was emphasized once again, which starts in the gesture of lifting and turning the thing and finds its provisional conclusion in the gene sequentialization.

Reference

Lévi-Strauss, Claude: La pensée sauvage. Paris 1962. Dt. Übers: Das wilde Denken. Aus dem Frz. von Hans Naumann. Frankfurt/M. 1997.

*We would like to emphazise that this is Lévi-Strauss’ terminology.

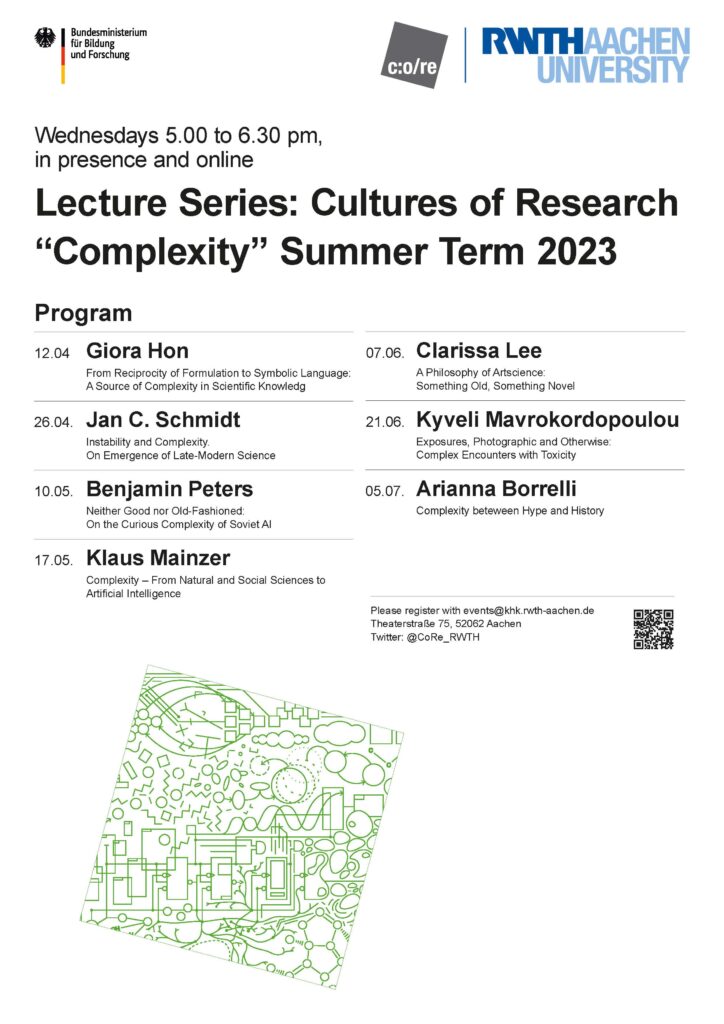

Lecture Series Summer 2023: Complexity

We are very pleased to announce the program for our lecture series during the summer 2023. The topic of this semester’s series of lectures is “Complexity”. The program gives and overview of the work of some of our fellows but also includes renomated researches from philosophy and theory of sicence such as Prof. Klaus Mainzer with his lecture on “Complexity – From Natural and Social Sciences to Artificial Intelligence”.

To take part either online or in presence, please register with events@khk.rwth-aachen.de

Research in Times of War – “The War Added One More Factor – the War Itself”

For over a year now the war is raging in Ukraine. Anna Laktionova and Svitlana Shcherbak, two philosophers from Kiev, left after the invasion. They are fellows at c:o/re, an advanced studies center at RWTH Aachen University that focuses on different research cultures and how they change in times of global challenges and transformations. War can have an impact on research, too. It first of all threatens and takes lives and destroys homes – but it can also radically change the scholarly landscape. Concidering the terror against civilians, I was hesitating for a long time to ask Anna and Svitlana about research in times of war, but I finally approached them and asked if they would be open to talk about their experiences during the past year. They agreed, although they both told me how tough and challenging it was to speak about this. I am very greatful that they shared their personal stories and professional perspectives.

Svitlana Shcherbak

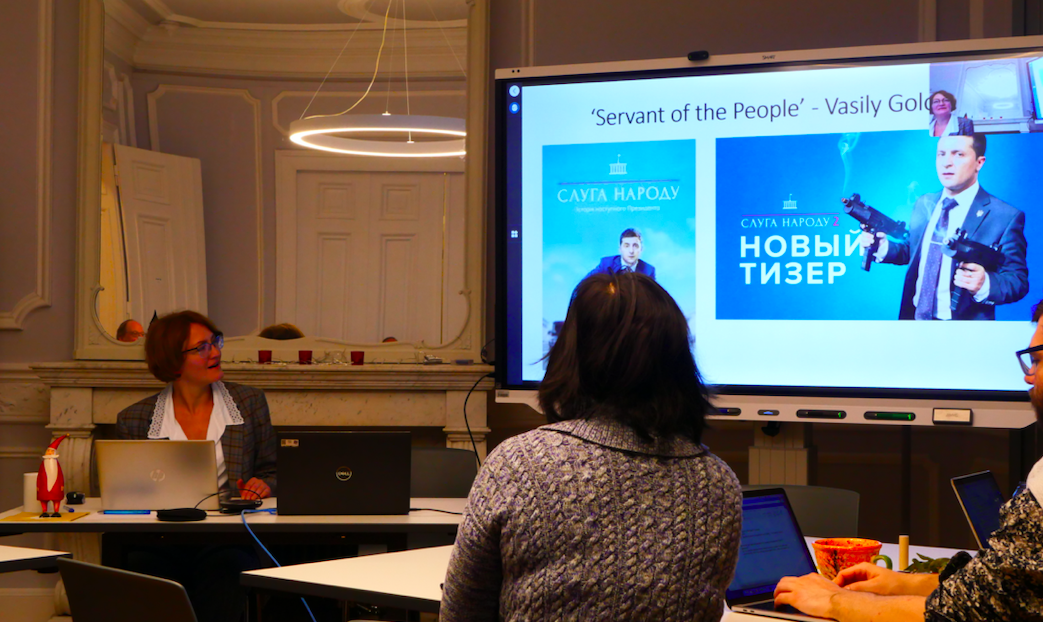

Svitlana Shcherback is a researcher with a professional focus on political philosophy, discourse analysis and the political development of Post-Soviet states. She has years of experience in various (international) research projects, for example with the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine or with the Catholic University of America, Washington, DC. In her current studies as a c:o/re fellow, Svitlana works on the aspect of “modernization” in ideological discourses of Post-Soviet states namely in Russia and Ukraine

Stefanie Haupt: When did you become certain that the Russian government was serious about attacking Ukraine? May I ask how you experienced the weeks before, the day of the invasion and the weeks following it? What were your thoughts and when did you decide to leave?

Svitlana Shcherback: It is still not easy to remember the first days of the war. When the embassies of the USA and European countries announced the evacuation of their staff, it became clear that the threat of a Russian attack was quite real. I understood that it was a realistic scenario, but I did not want to believe it until the very end. The slightest hope remained that it was just a bad joke. It seemed to be unbelievable that Putin could make such a decision, which turned out to be a disaster not only for Ukraine, but also for Russia. It was such a terrible and stupid decision that I hoped until the very last minute that it would never happen.

However, a premonition of war was in the air, and in my daily life I acted as if the war was inevitable. I was getting ready for it, buying some important things like medicines and putting my current affairs in order. I used to shop abroad via the Internet; the Ukrainian postal services were quite reliable and fast. However, just before the war, I resisted the temptation to shop abroad, assuming that I would not get it because of the war.

On February 19th, I was together with my children at a concert in the Kiev Philharmonic Hall, we listened to Mozart’s Requiem. Later we often remembered that concert; it was so symbolic… On the 24th of February, we were woken up at about 5 a.m. by the sound of a rocket flying over our house. I remember the feeling – it has happened; there is no more hope, it is war! My kids were frightened, but I felt neither fear, nor despair – the waiting was difficult, but all that was needed now was action. Nobody knew what was going to happen. We lived in the outskirts of Kiev, not far from Gostomel and Bucha, and I never knew that waking up at dawn to the sounds of fighting was going to be our daily routine, that we would learn to identify the sounds of rockets and to determine the direction of fire. In short, that we would acquire the skills that my relatives in Donetsk had acquired long ago, and far better than us.

I had stayed in Kiev for two weeks with my son, while my husband evacuated our daughter and his parents to the countryside near Cherkassy. My mother’s house is in Gostomel, near to the airfield where the Russian airborne troops landed. I was so happy that she was in Germany at the time, because the fighting was right next to her house. It miraculously survived, although it was left without windows and partly without a roof.

From the first day of the war, all shops except the large supermarkets were closed, public transport was at a standstill, and getting to other parts of the city, especially across the Dnipro River, became a challenge. Kiev was being attacked by the Russians from different sides, and the city streets were partially blocked by anti-tank hedgehogs and cement blocks. Our daily routine had been reduced to the task of survival.

It was clear that the Russians overestimated their military forces and misjudged the situation in Ukraine. They expected an easy and quick victory, obviously believing their own propaganda cliché about the ‘Nazi government’ and ‘pro-Russian people’ in Ukraine. But it soon became obvious that the war would be long and bloody. I did not want to put the children in danger, especially my daughter – she has diabetes, and I realized that because of the war it would be difficult to provide her with all the medicines and equipment she needs to live.

In the early days of the war, it was extremely difficult to leave Kiev. We could only get out of the city by car or on so-called evacuation trains, overrun by crowds of frightened people. The roads were also jammed, there were roadblocks and traffic jam for miles, and it was very hard to get petrol. It took me a while to decide what to do and where to go, and to get ready for the long journey with two kids. It was scary to go almost nowhere with children. I also waited for the flow of refugees to subside. In the end, we had to take an evacuation train from Cherkassy to Lviv, and, you know, after that trip, other troubles seemed less troublesome than before. I decided to go to Germany, because my mother lived in Ober-Olm, near Mainz.

Two weeks of our stay in Kiev had not passed without a trace. When we arrived in Germany, for the first time we tried to identify the type and direction of a flying rocket, when we heard the sound of an airplane. We forgot that airplanes could be peaceful. And we had only been in Kiev for two weeks. I can only imagine what people in Mariupol or Kharkiv must have gone through.

When the war started, I was in pieces for several reasons. First and foremost, war means death. So many people have already died, and I do not know how many more deaths the war will bring. I was born in the East of Ukraine, in Donetsk. I spent part of my childhood in the countryside, near Zaporizhia. Hot summer days, endless meadows and fields of wheat and sunflowers, cut through with woodland belts, and the high blue sky above are still before my eyes. It is an arid steppe zone; there is no lush greenery, no big forests, no large rivers, just endless steppe and sunshine. Small villages scattered along the road. It pains me deeply to think that this land, my home country, is now being torn apart by the war.

I am a Russian-speaking half-Russian and half-Ukrainian, and although I have never identified with Russia, Russian culture is a part of my background. I know that Russia is very heterogeneous, as Ukraine is and even more so. I took the Russian invasion as a shot in the temple to all Russian-speaking people all over the world, not just in Ukraine. Attacking Ukraine was the worst thing the Russian authorities could have ever done for Russians.

This war is a real tragedy for both Ukrainian and Russian people, and we will have to deal with dire consequences of the war for many years… So many deaths, so much blood and destruction. As a child I often watched films and read books about war, mostly the Soviet ones, but not only. These books and films were different; most of them were rather propagandistic, showing the war just in black and white. But there were also films and books that reflected on the experience of war. For example, Ivan’s Childhood by Andrei Tarkovsky, Trial on the Road by Alexei German, Go and See by Elem Klimov, The White Guard by Mikhail Bulgakov, All is Quite on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque. Even as a child, I understood how terrible the wars must have been. War cripples the human soul. As my son said after coming to Germany and returning to a normal life: war should not exist. I believed that it would never happen again, and in my nightmares, I could not have dreamed that it would affect us directly… It seems incredible that this war was initiated by the country that suffered so much during WWII and that used this traumatic experience and the memory of the war as a basis for consolidating society. It seems that most Russians have not yet understood that from now on the responsibility for starting the war lies with Russia and that their children will have to deal with it.

However, I do not support the idea of cancelling everything that has to do with Russia. On the contrary, I think that this tendency makes Russians feel an existential threat and support Putin in his justification of the war as a forced necessity, mobilises them.

Stefanie: It is now one year since the war in Ukraine began. How did you manage to settle in and find routines at RWTH and in the city of Aachen? How did your professional life as a philosopher change? Does the war impact your research agenda? And if so, how?

Svitlana: Of course, the evacuation was not easy. I remember the evacuation train to Lviv, a city in the West of Ukraine. It was packed with people like sardines, and the journey took 16 hours. Let me not remember that time any more. War is always hard; it is a situation of the ultimate existential challenge, the encounter with death, and the ruin of infrastructure and institutions that form the basis of everyday routine.

We stayed at my mother’s for a short time. I soon found the opportunity to apply for a fellowship at the RWTH, and a week later we arrived in Aachen. In Germany, we were greeted with sympathy and compassion from the very beginning. I am so grateful to the people who met us and helped us, in particular to Rosemarie and Engelbert Gabel from Ober-Olm. In Aachen we stayed with Christina Veenhues, who also supported us, helped us get settled in and became a good friend of mine. It is not easy to name all the people who helped us, but I would like to express my gratitude to Ana de la Varga, Gabriele Gramelsberger, Julia Arndt and Mathias Sannemann, my children’s class teacher at the Anne-Frank-Gymnasium.

I am convinced that any research agenda you are deeply involved in has to be relevant to something really important in your life. Of course, the war has affected my research agenda.

In recent years, I have focused on the political and economic processes in Ukraine and how they are intertwined and influence each other. I was rather critical of the policies of the Ukrainian authorities during Petro Poroshenko’s presidency. In my opinion, the government focused too much on identity politics and neglected economic and social reforms. I was also concerned about the fate of southern and eastern regions of Ukraine. The problem was that the Ukrainian national project postulated a strong link between the preferred language of everyday communication and ethno-political identity (pro-Russian/pro-Ukrainian). These regions were largely Russian-speaking and a mixture of both Ukrainian and Russian cultures, and did not fit into this concept of Ukrainian identity. They were a kind of bridge between Ukraine and Russia; not surprisingly, they ended up becoming a ‘conflict zone’ (I owe this bridge metaphor to my colleague Roland Wittje).

Being a partisan of civic nationhood as a political identity built around shared citizenship within the state, I wanted Ukraine to be more democratic and liberal than it was and was going to be. That is why I was interested not only in applied research on political processes in Russia and Ukraine, but also in common issues of political philosophy. I strongly believe that understanding the post-communist space requires attention to the normative aspects of the ‘political’ and the analysis of developed countries, which turned out to be a kind of supplier and pattern of normativity for post-communist countries. Moreover, I believe that studying only endogenous factors is not sufficient for understanding the problems and challenges faced by post-communist countries, because their institutional configurations were largely formed in response to external influences, even if indirect.

The war added one more factor – the war itself. It heated up my interest in questions of ideology, propaganda, information warfare, post-truth and other issues related to political epistemology. I was interested in them before, but after the outbreak of the war, my interest to them increased enormously. The war in Ukraine, despite localised, has critically changed the world, and it will never be the same again. I mean not only in terms of geopolitical configuration, but also economic and institutional change. The conflict is far from over, and the question of what the world will look like after it is still open.

Stefanie: What are the circumstances under which researchers in Ukraine work? What would you say how the war is impacting academia there and in the post-Soviet states general?

Svitlana: Working conditions for Ukrainian scientists are not the best at the moment. The damage to Ukraine’s energy infrastructure has had the most negative impact because people’s lives are closely linked to the times when electricity is on. They often have to work at night.

The electricity situation is better now, but questions of how to survive on a daily basis are acute. Few of our colleagues have gone to the front, except on their own initiative, because there is a reservation for the conscription of scientists into the army.

Of course, any war is an existential challenge; it requires a special kind of reflection. On the one hand, we need to take a critical look at the processes in the post-Soviet space that made the war possible and, at some point, even inevitable. This reflection may turn out to be difficult, because the processes in Ukraine itself have been and continue to be very complex and controversial. On the other hand, the moral dimension of the war needs to be considered.

The war occupies the prominent place in the reflections of Ukrainian philosophers and social scientists – round tables, articles, journal issues and monographs are devoted to it. At the same time, even before the war, the agenda of Ukrainian public intellectuals tended to be rather right-wing than left-wing focusing mainly on identity politics. Now, for obvious reasons, it has become more radical. Beyond identity politics, Ukrainian researchers focus on moral issues, trying not only to conceptualise the existential and moral meaning of war, but also to describe current social processes and conflicts in terms of good and evil. I would even say that the front is now not only on the battlefields, but also on the pages of academic journals. Many of our colleagues define their task in terms of the war – to strengthen the consolidation of both Ukrainian and Western societies in their opposition to Russia.

I remember a conversation with a colleague who told me of his idea to write a book about Russia as a “Nazi” state. I argued that one could talk about fascist tendencies in Russia, but not about Nazism. He agreed after a short discussion, but said that for him the writing of such a book was a kind of fight against Russia. Never mind that it would mean deliberately deluding the public (against one’s own better knowledge).

I am aware that involvement is inevitable; as a good song about the Second World War says, ‘I am not involved in the war; the war is involved in me’ (thanks to Ilya Vorobyev for the idea). However, I consider critical reflection to be an essential part of our professional task and our professional ethics, and I personally cannot refuse it.

The focus of most Ukrainian intellectuals on identity politics leads to a neglect of the problems with various reforms, especially the labour law reform that is currently being implemented in Ukraine under the guise of a ban on criticism of the government’s actions during the war. I would recommend reading a recent article by Volodymyr Ishchenko in the New Left Review on this issue.

Stefanie: Do you observe differences and/or similarities between research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen? And in what direction does your own research develop now?

Svitlana: The question of the research cultures is rather complicated to answer in a nutshell. I see both differences and similarities between the research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen, resulting on the one hand from the Soviet past of Ukrainian philosophy, and on the other hand from its kind of postcolonial status today. One of the most striking differences between the research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen is the lack of theoretical discussions among Ukrainian philosophers. The question of the peculiarities of Soviet philosophy and its institutional functions has been discussed many times, mainly by Russian philosophers. Despite the fact that philosophy in the Soviet Union was saturated with ideology, there was some free space for thought. Of course, the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin created a corpus of ‘sacred texts’ that described reality in the only possible and truthful way, but they were not comprehensive. In particular, the development of science and the emergence of new disciplines had raised many questions. Philosophy existed in this gap between the prescribed ideological ‘credo’ and the living reality. Discussions sometimes did not follow the logic of their own discursive field, but the logic of the apparatus struggle. However, the common language and methodological framework enabled discussions between philosophers and scientists in the Soviet Union.

After the collapse of the USSR, the philosophical space became fragmented. First, national languages of philosophizing began to develop. Russian lost its function as the main language of communication, and Moscow ceased to be the centre of attraction for intellectuals from the post-Soviet space. Second, Ukrainian researchers were mostly re-oriented towards different philosophical schools and centres in Europe and the USA. They began to play the role of representatives of various Western philosophical schools in Ukraine. Some Ukrainian philosophers see their main task as representing the current trends and disciplines of Western philosophy at the university and in translating of relevant texts. Some do hermeneutics or phenomenology, others communicative or analytical philosophy, and so on. This means that philosophy in Ukraine is more receptive than productive.

Of course, Ukrainian philosophers’ work is not just a historical and philosophical representation of the Western philosophy. There is a number of original and interesting works in Ukrainian philosophy. But they are thematically and methodologically linked to and included in Western philosophical discourses. These books and articles are often published in other languages and become part of the work of researchers from Ukraine, but not of Ukrainian philosophy.

My sketch is rather superficial, I must admit. There are some books devoted to philosophy in the post-Soviet countries, particularly in Ukraine. I would recommend, for example, Mykhailo Minakov (ed.), Philosophy Unchained: Developments in Post-Soviet Philosophical Thought (2023).

Stefanie: I think, your analysis is far from superficial. Thank you Svitlana, for sharing not only your professional perspectives on the academic developments in Ukraine but also on your very personal experiences in the past year.

Svitlana: Thanks, Stefanie, for your in-depth questions. I very much appreciate the opportunity to speak out as one of Ukrainian voices.

Research in Times of War – “Scientific Life Somehow Goes on…”

For over a year now the war is raging in Ukraine. Anna Laktionova and Svitlana Shcherbak, two philosophers from Kiev, left after the invasion. They are fellows at c:o/re, an advanced studies center at RWTH Aachen University that focuses on different research cultures and how they change in times of global challenges and transformations. War can have an impact on research, too. It first of all threatens and takes lives and destroys homes – but it can also radically change the scholarly landscape. Concidering the terror against civilians, I was hesitating for a long time to ask Anna and Svitlana about research in times of war, but I finally approached them and asked if they would be open to talk about their experiences during the past year. They agreed, although they both told me how tough and challenging it was to speak about this. I am very greatful that they shared their personal stories and professional perspectives.

Anna Laktionova

Anna Laktionova is Professor of the Department of Theoretical and Practical Philosophy at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine. Among other topics, such as theory of knowledge, and the legacy of Ludwig Wittgenstein, she explores the reciprocally additive character of the relation between “is” and “ought”. In her research project as a c:o/re fellow, Anna explores the possibilities of engaging Philosophy of Technology and Philosophy of Science with Philosophy of Action and Agency.

Stefanie Haupt: I remember waking up in the morning of the 24th of February 2022 to the news of Russia invading Ukraine. Although in retrospect everything pointed towards it – the occupation of Crimea in 2014, the weeks and days leading up to the war, the escalating rhetoric and actions – I was still shocked and could not believe it was actually happening. Looking back, I think that was naïve maybe. When did you become certain that the Russian government was serious about attacking Ukraine? How did you experience the weeks before, the day of the invasion and the weeks following it? What were your thoughts and when did you decide to leave?

Anna Laktionova: Even at 4.00 a.m. on the 24th of February 2022, early morning, when I was not able to fall asleep and I had been watching different news and information on the internet, I could not believe it to be possible. But then after two hours I woke up by the call from my brother telling me that there was already bombing of the North of Kyiv.

Since February, 7th, 2022, Vera, my 1-year-old daughter, my husband, and his mother (my mother-in-law, 82 years old) had already been in a rented flat in Uzhgorod (a nice town in the Western part of Ukraine, about 900 km from Kyiv). We had planned to spend half of the year there (the nature, climate etc. is very nice). But we also had a weird intuition about the Russian attack. We thought it would be much easier if I joined my family later than running away from Kyiv all together. As Covid was still spreading at that time, my teaching in the University was online, so I intended to join the family as soon as I felt ok – I did not feel well after I stopped breastfeeding Vera. So, no one in my family believed in a real possibility of war; but we had some intuitions, discussed them and decided not to risk our only child’s safety.

On the 24th of February 2022 at 8.00 a.m., I was already driving a car to Western Ukraine. I don’t have a car; from 6.00 till 7.45 I had been calling everyone of my close and not-so-close friends asking about the possibility to join someone who was heading West, explaining that I was alone, no luggage, just a knapsack (I took just documents, available money; not thinking about anything – even forgot my glasses as I was wearing contact lenses); and that I can drive (I have a driver’s license but no experience in driving as I don’t own a car anymore). Some friends of friends of friends had a car and old parents whom they wanted to send to the West, so I drove them to the small town Stryi close to the Carpathians. The road was extremely busy, the speed was mostly about 20 to 50 km per hour; it took us a bit more than 24 hours to get there. From there I got to Uzhgorod by local trains… On the way from Kyiv to the West, I saw Russian helicopters, aircrafts…

After a few days the possibility of a fellowship in KHK c:o/re Aachen opened up and I accepted it. I am very thankful to many foreign colleagues for trying to find ways of helping me! Me, my daughter, my mother-in-law, we crossed the border between Ukraine and Slovakia by foot on the 4th of March (no cars were allowed to pass through). My former classmates (who emigrated to Germany about 10 years ago) picked us up on the Slovakian side and we drove to Germany. On the border the situation was ‘very touching’: many men were accompanying women with children, helping with the luggage to the point of crossing the border, kissing, crying, and remaining on the Ukrainian side…

Stefanie: I can hardly imagine how much stress and uncertainty you must have experienced during this time. Did you manage to settle in and find routines at RWTH and in the city of Aachen? How did your professional life as a philosopher change? How does the war impact your research?

Anna: In Aachen, colleagues and staff from KHK c:o/re and RWTH were very kind and supportive (to name just a few: Gabriele Gramelsberger, Ana de la Varga, Julia Arndt). They and their friends helped us with everything: documents, finding a place to stay and live (the family of the owners of a flat where we live, the neighbours are also incredibly kind and caring), explaining about peculiarities of German institutions (the situation has also been challenging for them) and habits, also with finding a kindergarden for Vera (but she still doesn’t stay for more than one hour there without me) etc. etc. etc. I remember that in March and April on the streets I was meeting more and more Ukrainian women and children every day… Our situation in Aachen has been lucky enough. We are very thankful to many German people for the help, support, care!

My personal life has been and still is very much engaged with my daughter. It influences my professional life, my daughter is the first priority to me. Everything has been and still is not easy. I cannot participate in the professional life as much as I would like to and as I used to. The fellowship opened up new interesting very promising paths for my investigations, but I cannot accomplish them as largely as I want due to my personal situation.

Stefanie: Do you have colleagues in your private and professional network that work at research institutions and universities in Ukraine? Do you know how the situation is for them? I know that you are also still teaching online. How is the situation for your students?

Anna: Colleagues in Ukraine are holding on. Everything is online, sometimes not online but by email correspondence because of problems with electricity, internet, unsafety, air raid alerts… Many of them are helping to support the Ukrainian Army…

Officially, being a fellow, I don’t have to teach, but I am continuing to supervise some post-graduate students and future magisters. I was also asked by the administration of the faculty from Kyiv to continue teaching some of my courses online, which I do. Some students are outside Ukraine, some stay at home, often not in Kyiv. Meeting online is not always successful: air alarms happen at different times and in different districts of Kyiv and parts of Ukraine. Often the communication is by e-mail correspondence and individual zoom-meetings. Some students are at war, some volunteer in the helping infrastructure. Last year, I was member in several PhD and Doctor of Science committees. Scientific life somehow goes on…

Stefanie: Thank you so much, Anna, for sharing very difficult and personal experiences!

Navigating Interdisciplinarity

If you would like to know more about the Navigating Interdiscplinarity workshop, which was organized by c:o/re, together with CAPAS and the Marsilius Kolleg Heidelberg, which hosted it, the CAPAS newsletter features an insightful article, here. You can also see our previous reflexion on the workshop, on the c:o/re website, here.

Historicizing STS @ c:o/re: Turning points in reflections on science and technology

GABRIELE GRAMELSBERGER, ARIANNA BORRELLI, CLARISA AI LING LEE, KYVELI MAVROKORDOPOULOU, BENJAMIN PETERS, JAN C. SCHMIDT, ROLAND WITTJE

Photographer: Jule Janßen

On March 14th and 15th the workshop Turning points in reflections on science and technology: Toward historicizing STS took place at c:o/re. The aim of this event was to investigate the turning points in the intellectual history of Science and Technology Studies (STS) over the course of the 20th and 21st Centuries. Discussions converged to open up STS by historicizing this area of inquiry through explorations of the various turns in its development. As such, the meeting generated debates on the broad spectrum of notions of historicizing STS, as well of STS per se. It illustrated the interdisciplinary and multi-perspective study of STS that is being undertaken at c:o/re.

The event was organized in a carefully coordinated collaboration between c:o/re director Gabriele Gramelsberger and c:o/re research fellows. It served as a focused, c:o/re warm-up for the well-known STS Hub, which followed it, also hosted at RWTH Aachen University and organized by c:o/re director Stefan Böschen and other colleagues. The discussions benefitted from the attendance of Professor Ulrike Felt, who also delivered a keynote talk at the STS hub and is short term senior fellow at c:o/re during March 2023.

After Gabriele Gramelsberger, the main organizer of the Historicizing STS workshop, welcomed the participants to our Research Centre and explained the rationale of this meeting, c:o/re fellows Arianna Borrelli and Roland Wittje started off the academic debate. They chaired the panel Turning from History of Ideas and Artifacts to Practices and Society, with a focus on the increasingly close interplay between history of Science and Technology and STS, on the one hand and STS on the other, of which Lisa Onaga (Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin) and Carsten Reinhardt (Bielefeld University) provided impressive examples.

Photographer: Jule Janßen.

Lisa Onaga explored the practical turn in STS by focusing on silk craft. To recontextualize 20th Century Japanese modernisation and offer an example of how a community may reclaim its heritage, Onaga observed what she terms archipelagic thinking, that is, “seeing like an island”. Through this epistemic prism she explained how a remote community is aware of its being perceived peripheral while acknowledging itself as central to itself.

In his presentation, Residual Uncertainty in the Long Twentieth Century, Carsten Reinhardt addressed the Anthropocene through residue, as an analytical notion. This inquiry leads Reinhardt to a consideration of un/certainty, as a tension between striving for certainty and maintaining uncertainty. The debate pointed to the importance of reflecting on modernity through non-modern means.

As the second panel, c:ore fellows Benjamin Peters and Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou chaired Turning from Humans to Non-Humans, in a critical examination on anthropocentrism and its limits in the study of science and technology. Their invited speakers featured rising young scholars Salome Rodeck (Max Planck Institute for History of Science, Berlin) and Vanessa Bateman (Maastricht University).

Photographer: Jule Janßen.

Salome Rodeck presented on Hawaiian experiments, new imperatives, referring to Donna Haraway and reflecting on symbiosis science. Drawing also on the pioneering work of Lynn Margulis and the political turbulence of the 1960s and 1970s, Rodeck advanced a historically informed argument that dislocates anthropocentrism in Haraway’s work, particularly around microbial organism cooperation.

Vanessa Bateman’s talk was titled Animal Histories: Moving Between/Across STS, Environmental History, and Visual Culture. She addressed the project Moving animals on the globalization of non-human animals. Particularly, Bateman reflected on how long-distance movements of non-domesticated animals were studied, represented, and managed in US national parks. Close consideration of how elk populations adapt to human infrastructures and semiotic-material objects, such as a human-made fence that is an obstruction in a species’ environment, suggests new territories for nonhuman STS.

Photographer: Jule Janßen.

The third panel, “Turning points as epistemic shifts/epochal breaks”, was chaired by the c:o/re fellows Clarissa Ai Ling Lee and Jan C. Schmidt. In this panel, Andreas Kaminski (Darmstadt Technical University) asked whether ‘Hinge propositions’ are a way to identify epochal breaks? Following major epistemology scholars, from Thomas Kuhn to Friedemann Mattern, Kaminski pondered on how the world of observers changes once with the emergence of new ideas (or paradigms), through the deployment of Wittgenstein’s hinge propositions. Hinge propositions allow one to draw on the emergence of new expected, imagined and actual worlds. Hinge propositions could be used in the world-building of any world (including fictional worlds) so that the reader/audience/user/inhabitants of such world could take for granted that the rules governing such worlds are a priori determined and ‘historical,’ so that they could be ready to be deployed to emergent/new worlds. Therefore, hinge proposition is a fruitful instrument for conceptualizing turning points, shifts and epochal breaks.

Clarissa Lee and Jan C. Schmidt wrapped up the discussions through a focused reflection on this third panel as well as on the workshop generally. In the closing, they call on the participants to reflect on what STS means by reminding them of the ‘messy’ genealogy that had made up the history of STS as a field and domain. Clarissa asked everyone to reflect on how topics, concepts and methods are co-opted into STS knowledge practices, and to consider the deliberations that had allowed new fields to be co-opted into a ballooning STS.

The c:o/re team is grateful to the participants and, of course, to the c:o/re fellows who made possible this interesting and insightful event.

Photographer: Jule Janßen