For over a year now the war is raging in Ukraine. Anna Laktionova and Svitlana Shcherbak, two philosophers from Kiev, left after the invasion. They are fellows at c:o/re, an advanced studies center at RWTH Aachen University that focuses on different research cultures and how they change in times of global challenges and transformations. War can have an impact on research, too. It first of all threatens and takes lives and destroys homes – but it can also radically change the scholarly landscape. Concidering the terror against civilians, I was hesitating for a long time to ask Anna and Svitlana about research in times of war, but I finally approached them and asked if they would be open to talk about their experiences during the past year. They agreed, although they both told me how tough and challenging it was to speak about this. I am very greatful that they shared their personal stories and professional perspectives.

Svitlana Shcherbak

Svitlana Shcherback is a researcher with a professional focus on political philosophy, discourse analysis and the political development of Post-Soviet states. She has years of experience in various (international) research projects, for example with the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine or with the Catholic University of America, Washington, DC. In her current studies as a c:o/re fellow, Svitlana works on the aspect of “modernization” in ideological discourses of Post-Soviet states namely in Russia and Ukraine

Stefanie Haupt: When did you become certain that the Russian government was serious about attacking Ukraine? May I ask how you experienced the weeks before, the day of the invasion and the weeks following it? What were your thoughts and when did you decide to leave?

Svitlana Shcherback: It is still not easy to remember the first days of the war. When the embassies of the USA and European countries announced the evacuation of their staff, it became clear that the threat of a Russian attack was quite real. I understood that it was a realistic scenario, but I did not want to believe it until the very end. The slightest hope remained that it was just a bad joke. It seemed to be unbelievable that Putin could make such a decision, which turned out to be a disaster not only for Ukraine, but also for Russia. It was such a terrible and stupid decision that I hoped until the very last minute that it would never happen.

However, a premonition of war was in the air, and in my daily life I acted as if the war was inevitable. I was getting ready for it, buying some important things like medicines and putting my current affairs in order. I used to shop abroad via the Internet; the Ukrainian postal services were quite reliable and fast. However, just before the war, I resisted the temptation to shop abroad, assuming that I would not get it because of the war.

On February 19th, I was together with my children at a concert in the Kiev Philharmonic Hall, we listened to Mozart’s Requiem. Later we often remembered that concert; it was so symbolic… On the 24th of February, we were woken up at about 5 a.m. by the sound of a rocket flying over our house. I remember the feeling – it has happened; there is no more hope, it is war! My kids were frightened, but I felt neither fear, nor despair – the waiting was difficult, but all that was needed now was action. Nobody knew what was going to happen. We lived in the outskirts of Kiev, not far from Gostomel and Bucha, and I never knew that waking up at dawn to the sounds of fighting was going to be our daily routine, that we would learn to identify the sounds of rockets and to determine the direction of fire. In short, that we would acquire the skills that my relatives in Donetsk had acquired long ago, and far better than us.

I had stayed in Kiev for two weeks with my son, while my husband evacuated our daughter and his parents to the countryside near Cherkassy. My mother’s house is in Gostomel, near to the airfield where the Russian airborne troops landed. I was so happy that she was in Germany at the time, because the fighting was right next to her house. It miraculously survived, although it was left without windows and partly without a roof.

From the first day of the war, all shops except the large supermarkets were closed, public transport was at a standstill, and getting to other parts of the city, especially across the Dnipro River, became a challenge. Kiev was being attacked by the Russians from different sides, and the city streets were partially blocked by anti-tank hedgehogs and cement blocks. Our daily routine had been reduced to the task of survival.

It was clear that the Russians overestimated their military forces and misjudged the situation in Ukraine. They expected an easy and quick victory, obviously believing their own propaganda cliché about the ‘Nazi government’ and ‘pro-Russian people’ in Ukraine. But it soon became obvious that the war would be long and bloody. I did not want to put the children in danger, especially my daughter – she has diabetes, and I realized that because of the war it would be difficult to provide her with all the medicines and equipment she needs to live.

In the early days of the war, it was extremely difficult to leave Kiev. We could only get out of the city by car or on so-called evacuation trains, overrun by crowds of frightened people. The roads were also jammed, there were roadblocks and traffic jam for miles, and it was very hard to get petrol. It took me a while to decide what to do and where to go, and to get ready for the long journey with two kids. It was scary to go almost nowhere with children. I also waited for the flow of refugees to subside. In the end, we had to take an evacuation train from Cherkassy to Lviv, and, you know, after that trip, other troubles seemed less troublesome than before. I decided to go to Germany, because my mother lived in Ober-Olm, near Mainz.

Two weeks of our stay in Kiev had not passed without a trace. When we arrived in Germany, for the first time we tried to identify the type and direction of a flying rocket, when we heard the sound of an airplane. We forgot that airplanes could be peaceful. And we had only been in Kiev for two weeks. I can only imagine what people in Mariupol or Kharkiv must have gone through.

When the war started, I was in pieces for several reasons. First and foremost, war means death. So many people have already died, and I do not know how many more deaths the war will bring. I was born in the East of Ukraine, in Donetsk. I spent part of my childhood in the countryside, near Zaporizhia. Hot summer days, endless meadows and fields of wheat and sunflowers, cut through with woodland belts, and the high blue sky above are still before my eyes. It is an arid steppe zone; there is no lush greenery, no big forests, no large rivers, just endless steppe and sunshine. Small villages scattered along the road. It pains me deeply to think that this land, my home country, is now being torn apart by the war.

I am a Russian-speaking half-Russian and half-Ukrainian, and although I have never identified with Russia, Russian culture is a part of my background. I know that Russia is very heterogeneous, as Ukraine is and even more so. I took the Russian invasion as a shot in the temple to all Russian-speaking people all over the world, not just in Ukraine. Attacking Ukraine was the worst thing the Russian authorities could have ever done for Russians.

This war is a real tragedy for both Ukrainian and Russian people, and we will have to deal with dire consequences of the war for many years… So many deaths, so much blood and destruction. As a child I often watched films and read books about war, mostly the Soviet ones, but not only. These books and films were different; most of them were rather propagandistic, showing the war just in black and white. But there were also films and books that reflected on the experience of war. For example, Ivan’s Childhood by Andrei Tarkovsky, Trial on the Road by Alexei German, Go and See by Elem Klimov, The White Guard by Mikhail Bulgakov, All is Quite on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque. Even as a child, I understood how terrible the wars must have been. War cripples the human soul. As my son said after coming to Germany and returning to a normal life: war should not exist. I believed that it would never happen again, and in my nightmares, I could not have dreamed that it would affect us directly… It seems incredible that this war was initiated by the country that suffered so much during WWII and that used this traumatic experience and the memory of the war as a basis for consolidating society. It seems that most Russians have not yet understood that from now on the responsibility for starting the war lies with Russia and that their children will have to deal with it.

However, I do not support the idea of cancelling everything that has to do with Russia. On the contrary, I think that this tendency makes Russians feel an existential threat and support Putin in his justification of the war as a forced necessity, mobilises them.

Stefanie: It is now one year since the war in Ukraine began. How did you manage to settle in and find routines at RWTH and in the city of Aachen? How did your professional life as a philosopher change? Does the war impact your research agenda? And if so, how?

Svitlana: Of course, the evacuation was not easy. I remember the evacuation train to Lviv, a city in the West of Ukraine. It was packed with people like sardines, and the journey took 16 hours. Let me not remember that time any more. War is always hard; it is a situation of the ultimate existential challenge, the encounter with death, and the ruin of infrastructure and institutions that form the basis of everyday routine.

We stayed at my mother’s for a short time. I soon found the opportunity to apply for a fellowship at the RWTH, and a week later we arrived in Aachen. In Germany, we were greeted with sympathy and compassion from the very beginning. I am so grateful to the people who met us and helped us, in particular to Rosemarie and Engelbert Gabel from Ober-Olm. In Aachen we stayed with Christina Veenhues, who also supported us, helped us get settled in and became a good friend of mine. It is not easy to name all the people who helped us, but I would like to express my gratitude to Ana de la Varga, Gabriele Gramelsberger, Julia Arndt and Mathias Sannemann, my children’s class teacher at the Anne-Frank-Gymnasium.

I am convinced that any research agenda you are deeply involved in has to be relevant to something really important in your life. Of course, the war has affected my research agenda.

In recent years, I have focused on the political and economic processes in Ukraine and how they are intertwined and influence each other. I was rather critical of the policies of the Ukrainian authorities during Petro Poroshenko’s presidency. In my opinion, the government focused too much on identity politics and neglected economic and social reforms. I was also concerned about the fate of southern and eastern regions of Ukraine. The problem was that the Ukrainian national project postulated a strong link between the preferred language of everyday communication and ethno-political identity (pro-Russian/pro-Ukrainian). These regions were largely Russian-speaking and a mixture of both Ukrainian and Russian cultures, and did not fit into this concept of Ukrainian identity. They were a kind of bridge between Ukraine and Russia; not surprisingly, they ended up becoming a ‘conflict zone’ (I owe this bridge metaphor to my colleague Roland Wittje).

Being a partisan of civic nationhood as a political identity built around shared citizenship within the state, I wanted Ukraine to be more democratic and liberal than it was and was going to be. That is why I was interested not only in applied research on political processes in Russia and Ukraine, but also in common issues of political philosophy. I strongly believe that understanding the post-communist space requires attention to the normative aspects of the ‘political’ and the analysis of developed countries, which turned out to be a kind of supplier and pattern of normativity for post-communist countries. Moreover, I believe that studying only endogenous factors is not sufficient for understanding the problems and challenges faced by post-communist countries, because their institutional configurations were largely formed in response to external influences, even if indirect.

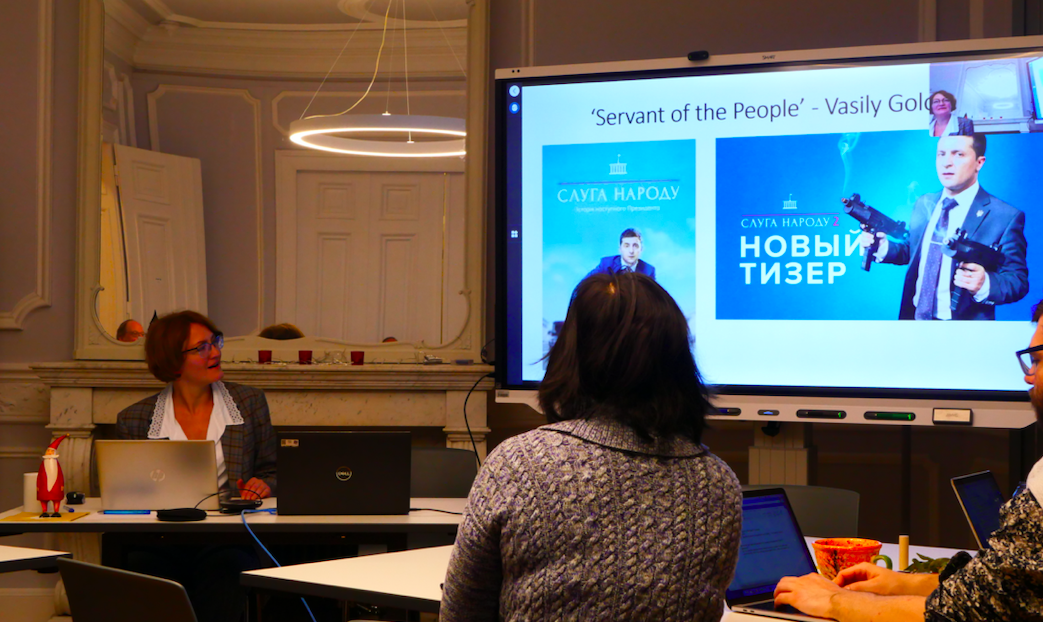

The war added one more factor – the war itself. It heated up my interest in questions of ideology, propaganda, information warfare, post-truth and other issues related to political epistemology. I was interested in them before, but after the outbreak of the war, my interest to them increased enormously. The war in Ukraine, despite localised, has critically changed the world, and it will never be the same again. I mean not only in terms of geopolitical configuration, but also economic and institutional change. The conflict is far from over, and the question of what the world will look like after it is still open.

Stefanie: What are the circumstances under which researchers in Ukraine work? What would you say how the war is impacting academia there and in the post-Soviet states general?

Svitlana: Working conditions for Ukrainian scientists are not the best at the moment. The damage to Ukraine’s energy infrastructure has had the most negative impact because people’s lives are closely linked to the times when electricity is on. They often have to work at night.

The electricity situation is better now, but questions of how to survive on a daily basis are acute. Few of our colleagues have gone to the front, except on their own initiative, because there is a reservation for the conscription of scientists into the army.

Of course, any war is an existential challenge; it requires a special kind of reflection. On the one hand, we need to take a critical look at the processes in the post-Soviet space that made the war possible and, at some point, even inevitable. This reflection may turn out to be difficult, because the processes in Ukraine itself have been and continue to be very complex and controversial. On the other hand, the moral dimension of the war needs to be considered.

The war occupies the prominent place in the reflections of Ukrainian philosophers and social scientists – round tables, articles, journal issues and monographs are devoted to it. At the same time, even before the war, the agenda of Ukrainian public intellectuals tended to be rather right-wing than left-wing focusing mainly on identity politics. Now, for obvious reasons, it has become more radical. Beyond identity politics, Ukrainian researchers focus on moral issues, trying not only to conceptualise the existential and moral meaning of war, but also to describe current social processes and conflicts in terms of good and evil. I would even say that the front is now not only on the battlefields, but also on the pages of academic journals. Many of our colleagues define their task in terms of the war – to strengthen the consolidation of both Ukrainian and Western societies in their opposition to Russia.

I remember a conversation with a colleague who told me of his idea to write a book about Russia as a “Nazi” state. I argued that one could talk about fascist tendencies in Russia, but not about Nazism. He agreed after a short discussion, but said that for him the writing of such a book was a kind of fight against Russia. Never mind that it would mean deliberately deluding the public (against one’s own better knowledge).

I am aware that involvement is inevitable; as a good song about the Second World War says, ‘I am not involved in the war; the war is involved in me’ (thanks to Ilya Vorobyev for the idea). However, I consider critical reflection to be an essential part of our professional task and our professional ethics, and I personally cannot refuse it.

The focus of most Ukrainian intellectuals on identity politics leads to a neglect of the problems with various reforms, especially the labour law reform that is currently being implemented in Ukraine under the guise of a ban on criticism of the government’s actions during the war. I would recommend reading a recent article by Volodymyr Ishchenko in the New Left Review on this issue.

Stefanie: Do you observe differences and/or similarities between research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen? And in what direction does your own research develop now?

Svitlana: The question of the research cultures is rather complicated to answer in a nutshell. I see both differences and similarities between the research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen, resulting on the one hand from the Soviet past of Ukrainian philosophy, and on the other hand from its kind of postcolonial status today. One of the most striking differences between the research cultures in Kiev and in Aachen is the lack of theoretical discussions among Ukrainian philosophers. The question of the peculiarities of Soviet philosophy and its institutional functions has been discussed many times, mainly by Russian philosophers. Despite the fact that philosophy in the Soviet Union was saturated with ideology, there was some free space for thought. Of course, the works of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin created a corpus of ‘sacred texts’ that described reality in the only possible and truthful way, but they were not comprehensive. In particular, the development of science and the emergence of new disciplines had raised many questions. Philosophy existed in this gap between the prescribed ideological ‘credo’ and the living reality. Discussions sometimes did not follow the logic of their own discursive field, but the logic of the apparatus struggle. However, the common language and methodological framework enabled discussions between philosophers and scientists in the Soviet Union.

After the collapse of the USSR, the philosophical space became fragmented. First, national languages of philosophizing began to develop. Russian lost its function as the main language of communication, and Moscow ceased to be the centre of attraction for intellectuals from the post-Soviet space. Second, Ukrainian researchers were mostly re-oriented towards different philosophical schools and centres in Europe and the USA. They began to play the role of representatives of various Western philosophical schools in Ukraine. Some Ukrainian philosophers see their main task as representing the current trends and disciplines of Western philosophy at the university and in translating of relevant texts. Some do hermeneutics or phenomenology, others communicative or analytical philosophy, and so on. This means that philosophy in Ukraine is more receptive than productive.

Of course, Ukrainian philosophers’ work is not just a historical and philosophical representation of the Western philosophy. There is a number of original and interesting works in Ukrainian philosophy. But they are thematically and methodologically linked to and included in Western philosophical discourses. These books and articles are often published in other languages and become part of the work of researchers from Ukraine, but not of Ukrainian philosophy.

My sketch is rather superficial, I must admit. There are some books devoted to philosophy in the post-Soviet countries, particularly in Ukraine. I would recommend, for example, Mykhailo Minakov (ed.), Philosophy Unchained: Developments in Post-Soviet Philosophical Thought (2023).

Stefanie: I think, your analysis is far from superficial. Thank you Svitlana, for sharing not only your professional perspectives on the academic developments in Ukraine but also on your very personal experiences in the past year.

Svitlana: Thanks, Stefanie, for your in-depth questions. I very much appreciate the opportunity to speak out as one of Ukrainian voices.

One Comment on “Research in Times of War – “The War Added One More Factor – the War Itself””

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback: c:o/re Highlights of 2023: A look back