A Field Trip to the Wandering Mines: Strange Ecologies and the Green Work of Environmental Mitigation

MATTHEW N. EISLER

In the Rhenish mining-industrial complex, the past, present, and future of geological and human time intersect. Over 30 million years, intertwined processes of evolutionary biology and geo-biochemistry produced thick seams of brown coal in the region now known as the Cologne Bay (Kölner Bucht) that began to be intensively mined from open pits from the late eighteenth century. As elsewhere, coal-based industrial enterprises enabled asymmetrical social development and came with environmental costs that human beings sought to mitigate with increasingly elaborate infrastructures of waste management. The resulting hybrid ecosystems exist in a state of fragile balance that requires constant effort to maintain, as a mid-May field trip to the Garzweiler and Hambach mines illustrated.

Matthew N. Eisler

c:o/re Fellow 01/25 – 12/25

Matthew N. Eisler is a lecturer in the Department of Humanities at the University of Strathclyde. He researches how ideology and policy inform practices of energy and materials conversion and shape social relations and environments.

I am a historian of clean and green technology and have become interested in the historical sociology of the “green work” of environmental mitigation, a project I am developing as a KHK fellow. I was curious to hear the perspectives of my companions on this question. The field trip was led by the retired hydrogeologist H. Georg Meiners, joined by Lars M. Blank, head of RWTH Aachen University’s Institute of Applied Microbiology, and Victor de Lorenzo, RWTH Kármán-Fellow and professor of research in the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), where he heads the Laboratory of Environmental Synthetic Biology at the National Center for Biotechnology. Georg spent much of his career investigating how the lignite mines affect local water quantity and quality while Lars and Victor research microorganisms capable of metabolizing industrial waste. They were eager to get out of the laboratory and lecture hall and into the field to see just what the microbial world is up against.

What we found was a vast “organic machine,” a term coined by the historian Richard White to connote large-scale industrial infrastructure in its ecological context. If the history of environmental mitigation can be characterized by a single phenomenon, it is ‘displacement:’ solve one problem and another pops up elsewhere unexpectedly. In the Rhenish mining complex (Reinisches Braunkohlerevier), we witness a cascading series of displacements. A key set of problems issue from the high sulphur content of lignite. In the 1970s and 1980s, lignite-burning German industry emitting sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides caused acid rain in faraway Sweden. Fitting power plants with scrubber technology fixed that problem but did nothing to mitigate emissions of climate-changing carbon dioxide. Moreover, sulphuric mine tailings can acidify soil and ground water. To neutralize this form of pollution, miners mix lime into the spoil.

Managing such problems is complicated by the vast scale of open cast mining. Garzweiler is an artificial canyon, and canyons can shape airflow and create their own weather systems. Georg had warned us to bundle up because it would be windy, and at Garzweiler, that wind is harvested as a resource. Energy planners have ringed the mine-canyon with dozens of giant wind turbines, exploiting an unintended ecological consequence of this industrial enterprise.

These winds cause numerous accidents on nearby motorways and also stir up particulates, a less-discussed problem of open cast mining, observes Lars. At Garzweiler’s eastern rim, where overburden is slowly processed into massive lime-laced mesas by giant earthmovers, a bouquet of hoses spray thousands of liters of water a minute in an effort to tamp down dust. But it is impossible to water all of the 40 square kilometers of the mine’s operating area. Scrubby vegetation growing atop the reclamation mesas fixes some of the particulate matter into place and I wonder aloud if this brush belt will grow into a green lung. Georg responds that this proto-forest is only an interim measure that will disappear according to the master mitigation plan of the terraformers of the Cologne Bay. From the 2030s on, the mine-canyons will be decommissioned and filled with water diverted from the Rhine, creating deep lakes in a project that could take until the end of the century and has many unknowns.

A less visible but equally problematic effect of the mine is on the realm of subterranean water. Garzweiler is surrounded by a vast network of wells, pipes, and pumps working constantly to lower the water table to enable coal excavation. This is a delicate operation. If the pumped water is not properly reinfiltrated back into the ground, says Georg, local forests, streams, lakes, and the underground springs for which the Aachen area is famous could be damaged or even destroyed.

The Cologne Bay is also a rich and important agricultural region that has become contested terrain in an unequal clash between industrialism and eco-activism. For a century, the mining enterprises followed the coal seams, and their historical progress, as depicted on topographic maps, resemble channels carved by giant coal-hungry worms munching their way through the landscape. These “wandering mines” have destroyed a number of farm communities in their path.

We visit the village of Keyenberg, a flashpoint in high-profile regional demonstrations against mine operator RWE in 2021 that became a monument to the uneven pace of environmental progress. Keyenberg is a ghost village. From the mid-2010s, it was slated to be engulfed by the Garzweiler mine and began to depopulate but when energy planners decided to phase out lignite, the abandoned village was left intact. Today, the place has the uncanny feel of a Chernobyl-like exclusion zone. A sign on one house reads “zu verschenken,” or in English, “to give away.” Such houses can be obtained for free, at the price of fixing them up and living near a windy and dusty mine-canyon. Georg says there is talk of housing war refugees here, and amidst the boarded-up buildings there are signs of life. One person, perched on a scaffold, repairs a house that boasts a well-tended hydrangea garden, activities suggestive of yet another form of green work heralding Keyenberg’s possible revival, or reincarnation.

The ongoing management of some of the wandering mine’s wastes, the conversion of its windy microclimate into clean energy, and the gradual reclamation of a portion of its disrupted hinterlands poses the conundrum of how to interpret the co-construction of such awesome desolations and their ingenious eco-infrastructures of life support. Contemporary environmental discourse imposes a dualistic moral-ethical framework of good (green) and bad (non-green) behaviors against which we are supposed to judge ourselves and others, declare a position as optimist or pessimist, and offer normative visions in a calculus that, as some argue, has centered generalized global processes over diverse local experiences of environments and environmental despoliation.

The case of the Rhenish coal belt calls attention to a particular set of conflicts, contradictions, and puzzles, and what the environmentalist Val Plumwood called “shadow spaces,” occluded from our subjective ecological visions, that invite further investigation. Human history would seem to vitiate the prospect of circumspect do-no-harm environmental activism advocated by the philosopher Arne Naess. In the imagined perspective of geological time, human beings might be perceived as acting in a near-simultaneous spasm of furious environment-altering activity.

It seems to me that the path to the kind of wise interventions Naess had in mind starts in gaining awareness of the perversities and paradoxes of myriad local projects of environmental mitigation. Understanding how human beings build organic machines like Garzweiler and its environs, learn how these strange ecologies operate as amalgams of human and natural agency, and live with the consequences might be a modest but necessary prelude to deciding the next set of mitigating moves.

I thank Georg Meiners for hosting and guiding this event and reviewing a draft of this essay, and Victor de Lorenzo and Lars Blank for enriching the experience with their insights and companionship.

Posted on June 6, 2025 by Jana Hambitzer

Melodic Pigments – An Experiment on the Relationship between Sound and Color

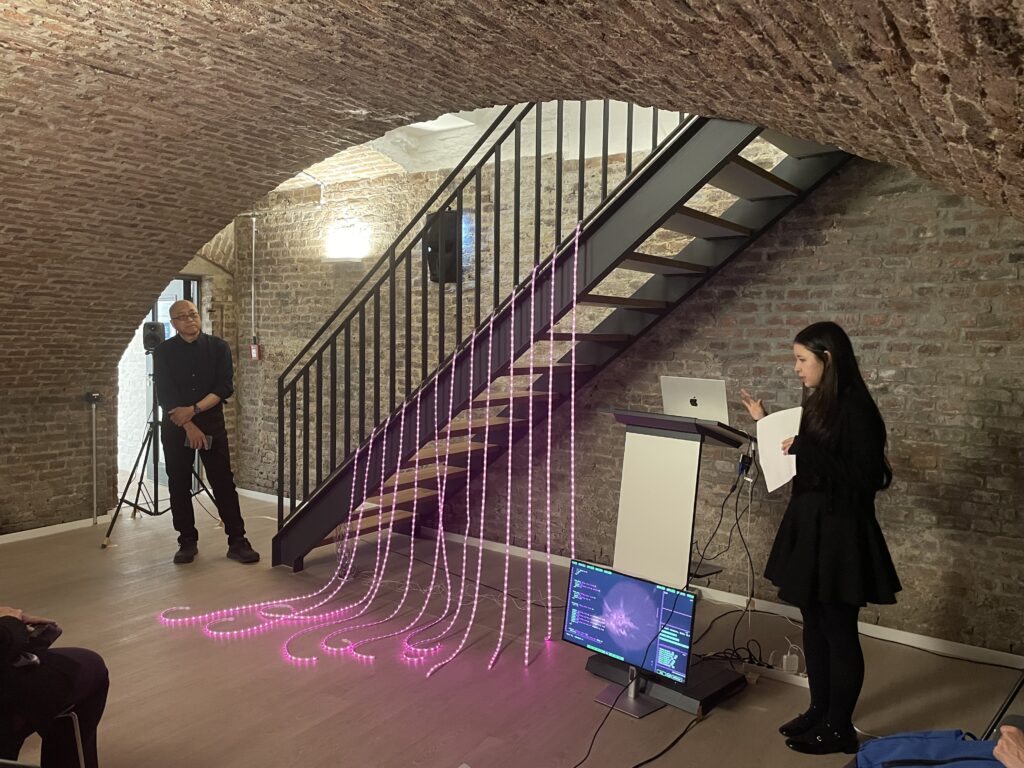

Is Artificial Intelligence (AI) capable of modeling and replicating human sensory associations? This question was explored at the KHK c:o/re on April 28, 2025, as part of the science-art installation experiment “Melodic Pigments: Exploring New Synesthesia” created by the Japanese media artist Yasmin Vega (Tokyo University of the Arts) in cooperation with KHK c:o/re alumni fellow Masahiko Hara (Institute of Science Tokyo).

The goal of the installation experiment is to explore the relationship between sound and color through the phenomenon of synesthesia, in which one sensory perception involuntarily triggers another. The primary focus is on chromesthesia, a form of auditory synesthesia in which sounds evoke the perception of colors.

During the performance, Yasmin Vega played electronic music using live programming, while an AI model trained on sound-color associations predicted and visualized corresponding colors in real time. The AI model used in this project was trained on subjective data reflecting Yasmin Vega’s personal associations between sound and color. Throughout the performance, the AI processed incoming sounds every three seconds and determined the corresponding colors based on the pre-trained data, thereby creating a fluid interplay between auditory and visual elements. The colors chosen by the AI were shown on a series of hanging light tubes and as morphing pattern on a computer screen.

The installation experiment seeks to explore the AI’s ability to model and replicate human sensory associations. The focus is on exploring internal visualization processes and the sensory capabilities of machines. Yasmin Vega’s performance demonstrated that the AI was able to recognize and replicate human perceptions while generating color-sound associations that matched the artist’s expectations.

This installation experiment builds on previous works on the integration of artistic strategies into science and technology that KHK c:o/re alumni fellow Masahiko Hara has engaged in during his fellowship. In January 2024, he presented the art installation “Unfelt Threshold” developed in collaboration with the artist Aoi Suwa that explored the perceptual capabilities of machines in response to unpredictable visual stimuli. Through these experiments, Masahiko Hara aims to open up new perspectives at the intersection of materials science and nanotechnology within scientific engineering. The interplay between science and artistic practice reflects a central research interest of the KHK c:o/re, which investigates how artistic methods can contribute to epistemic questions within an expanded framework of science and technology through performances such as “Melodic Pigments”.

Interview with Yasmin Vega

How do you perceive sound and color?

When I listen to a high-pitched sound, I imagine yellow. When I listen to a dark sound, like dark bass, I also imagine a dark color, like dark green or like deep purple. The volume of the sound also changes how I perceive it. If I listen to a loud sound, I imagine red. And even if I listen to the same melody, if it’s played with different instruments, I also imagine a different color.

What surprised you most about the visualizations of the AI?

What surprised me the most was how often the AI’s visualization matched the color that I actually imagine when I’m performing. And it almost felt like the AI could understand my personal sense of color. From this whole performance, I realized that how useful it can be to work with AI when it comes to expressing something that’s really personal and hard to explain to others or share with others.

What do you think about AI and art working together? Where do you see challenges?

I wanted to use the AI just as a tool in my artworks. I felt that if I collected the training data by myself and developed the model by myself, then using AI is just like using the tool. So, the final artwork was really my work. And I didn’t feel like just writing the prompt and letting the AI to generate the image is really artwork. That’s why I originally wanted to control the AI as much as possible, but now I feel a little bit more relaxed about it. Now I’m looking for the unpredictable results that come when I can’t freely control the AI. I can say that I’m not so cautious anymore.

One challenge I see is the amount of the data. This time I only used 300 samples to train the AI model. There are so many sounds in the world, so it’s basically impossible to cover all of it. But improving the model’s accuracy doesn’t automatically mean that the artwork itself gets better. So, I think the creative value comes from something more than just how smart or how accurate the AI is.

Photos and video by Jana Hambitzer

Posted on May 13, 2025 by Jana Hambitzer

“We can look forward to four more exciting years” – Interview with Gabriele Gramelsberger and Stefan Böschen

The Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re) at RWTH Aachen University will begin its second funding phase in May 2025. The German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) will fund the center for another four years. With the start of the second phase, KHK c:o/re directors Gabriele Gramelsberger and Stefan Böschen look back, reflect on the achievements and developments of the past four years, and set out the goals and expectations for the coming years.

Looking back over the past four years: What were the highlights of the first funding phase?

It is already a highlight that c:o/re is the first Käte Hamburger Kolleg at a technical university and will probably remain the only one. It is also the only center for advanced studies in history, philosophy, and sociology of science and technology worldwide. The first funding phase was a development phase. This development has been successfully completed. We got a wonderful location for this Kolleg on Theaterstraße and the best possible team. We have had great fellows in all four cohorts, with whom we have developed exciting intellectual perspectives in very different ways. In addition, we have been able to organize a large number of events, networks, and collaborations both within and outside RWTH. Therefore, there are plenty of highlights to report on from the first funding phase.

What are the lessons learned, especially with regard to the interdisciplinary exchange with the fellows?

Experience shows how demanding this collaboration ultimately is, but also how fruitful. You wouldn’t necessarily expect different branches of the humanities and social sciences to work together with natural sciences and technology, but they do. We also work intensively with our colleagues from the natural sciences and engineering. That’s why we’ve developed various formats like lab talks to make these collaborations easier. We’ve also developed projects with some fellows that are now being carried out in cooperation with the Human Technology Center (HumTec). The most important lesson learned, however, is certainly that this type of collaboration not only requires more time and a more relaxed attitude, but also that specific opportunities should be created so that the work can lead to joint results. Goal-orientation fuels interdisciplinary cooperation. In the “Software Group” (a working group at the KHK c:o/re – editor’s note), for example, an article was written with many fellows from a wide area of disciplines and published in Nature Computational Science.

What do you enjoy most about working at the KHK c:o/re?

It’s just wonderful that the KHK gives us a platform that allows us such unusual freedom in our research. This has to do with a number of important boundary conditions. On the one hand, generous funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) allows us to invite a large number of fellows from all over the world every year to work with us on fundamental questions in science. Second, we have a great team that not only supports the work but also enables us to work together on our research goals. Finally, we receive exceptional support from the Rectorate of RWTH Aachen University, which regards the work of the Kolleg as an important asset for its strategy for excellence.

What are the goals of the second funding phase?

In the second funding phase, we are taking seriously the feedback from last year’s evaluation of our research group. The evaluation went very well fostering our research profile more strongly. This will enable us to produce results of even greater relevance and visibility. Against this background, we are pursuing two lines of research, one dealing with the digitization of research (“Varieties of the Digital”) and the other with the cosmopolitization of science (“Varieties of Science”). These lines of inquiry are not only significant in their own right, but also allow us to advance the program of an integrated interdisciplinary methodology of science studies itself, which we bundle under the heading “Expanded STS”. Furthermore, we will link “Expanded STS” to the historical reflection of computing, philosophy of science, and STS. We are working on two book series. One will consist of three volumes dealing with the history, philosophy, and sociology of computing and computational science. The other will consist of two volumes on Expanded STS.

What are you looking forward to?

We can look forward to four more exciting years. We will certainly cultivate even more freedom for individual and joint research than we have done so far. In addition, the Kolleg allows us to further develop and strengthen our international networks related to our research topics. In this way, we hope not only to achieve insightful research results, but also to support the development of a special epistemic culture at our University. This is based on the ideal of tailor-made, integrated, interdisciplinary research practices for understanding science itself, but also for finding more targeted solutions to collective problems.

What challenges do you see in the current research landscape and how does the KHK c:o/re address them?

There are a number of significant changes in the research landscape. These can be described using the triad of transformation, transformation of science, and transformative research. These changes challenge our self-image as researchers, but also the institutionalized self-understanding of science. Although science represents an institutionalized special space for the production of epistemically sound knowledge, it is also increasingly caught up in the maelstrom of contemporary transformations. Making these transformations analyzable in terms of their structure and dynamics is the central concern of our research at the Kolleg.

What is your current research focus and how does it relate to your work at the KHK?

Gabriele Gramelsberger: My research focuses on a long-term narrative of the digitization of science as part of the philosophy of computer science. The history of computer science and computational science on the one hand and current developments towards AI on the other are linked to better understand today’s “digitality”. In my view, digitality began long before the invention of the digital computer in the 1940s. Digitality is the result of the operationalization of the mind of modern philosophy in the 18th century. In the 19th century, mathematics took over, and in the 20th century, engineering took over. However, with this broader perspective, we can better integrate the humanities and social sciences into the current understanding of the digital, which is dominated by science and technology. Above all, we need to better understand the cultural impact of software, which has become the general infrastructure of research and everyday life. Its cultural impact is based on the fact that programming has introduced a new and very powerful way of using written language that not only describes operations but also executes them. Nevertheless, it is a product of written language that is worthy of being archived as cultural heritage and researched by historians, philosophers and sociologists of science and technology.

Stefan Böschen: My research focuses on a wide range of issues in the sociology of science and expanded STS (science and technology studies). Of particular importance are the different forms of collaborative research in a variety of settings. These typically relate to a wide range of fields of innovation and transformation (from neuromorphic computing to a DC-driven energy transition). In this context, concepts of research infrastructures (such as living labs) or those of the analysis of innovation and transformation processes (such as innovation ecosystems) can be further developed. This also creates highly productive new interfaces with research at the Kolleg. For example, the form and dynamics of living labs can be examined in their region-specific differences and thus investigated with regard to the differences brought about by varieties of science (cultural-institutional varieties of scientificity).

What is your “culture of research”? How would you describe the way you conduct research?

Gabriele Gramelsberger: My research culture combines epistemic and historical research in order to better understand current developments. The historical dimension encompasses a wide range of interdisciplinary practices and aspects that I am interested in. Therefore, the Kolleg is the perfect place for me to live my research culture.

Stefan Böschen: My research culture can be characterized by the combination of engineering (I am a trained chemical engineer) and sociology. This has not only given me a keen interest in technology assessment and science and technology studies, but also a great enjoyment of interdisciplinary collaboration at the interfaces between very different disciplines. The productive connection between the various disciplines of science studies plays a particularly inspiring role for me.

The interview was conducted by Jana Hambitzer.

Posted on April 28, 2025 by Jana Hambitzer

Emotional AI in the Japanese and German Workplace: Exploring Cultural Diversity in AI Ethics as Variety of Science

STEFAN BÖSCHEN, MASAHIKO HARA, PETER MANTELLO AND ALIN OLTEANU

The Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re) is a partner on the project Emotional AI in the Japanese and German Workplace: Exploring Cultural Diversity in AI Ethics, led by Professor Peter Mantello of Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (APU) and funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The project has been ongoing for about a year, and in January 2025, c:o/re director Stefan Böschen and Alin Olteanu visited Professor Mantello and conducted a first field study in Japan for this project.

As the title claims, this project examines the developments in Emotional AI from a comparative perspective between Japan and Germany. Such research is, of course, conducted in the context of increasingly rapid developments in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). So far, these developments have occurred in waves. Phases of great innovative momentum alternated with phases in which this topic appeared dormant. The recent technological platform of large language models such as ChatGPT suggests that this field is now entering a phase of lasting and disruptive development. The great geopolitical competition between world regions is exemplified in the sudden appearance of China’s DeepSeek. These developments raise questions about the specific technological development under the respective cultural-institutional framework conditions. With its AI Act, the European Union has issued the strictest, risk-based regulation of AI, striking a balance between protection against technology and industrial development, while the United States and Japan appear, at least at the present moment, reluctant to lay down a concrete regulatory policy, preferring instead a market state approach.

Our project offers the opportunity to reflect not only on the specific challenges for science studies, but importantly, in the context of the increasingly quantified workplace, where insights can be fed into the varieties of science discussions pioneered at c:o/re. The following itinerary documents the journey of c:o/re director Stefan Böschen and former team member Alin Olteanu through Japan, together with Principal Investigator Peter Mantello, along with Co-Investigator Hiroshi Miyashita of Chuo University, and the local assistance of Masahiko Hara, an alumni fellow of c:o/re who graciously gave us his time to accompany us from Tokyo to Beppu. The following blog post outlines some of the places and people we met along the way, as well as revealing insights we achieved on this whirlwind one week journey.

Tokyo, Monday, January 13th – AI Workshop

On the 13th of January, a workshop on the Future of AI was held at Ritsumeikan University’s Tokyo Campus at Sapia Tower. Bringing together stakeholders from the private sector, academia, and non-governmental organizations, the workshop explored various risks and opportunities of AI development in Japan. Some of the speakers included researcher Nicole Müller from the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ), who spoke about the implications of Emotional AI and Extended Reality, Imam Habib, managing director of Menlo Park, a venture capital firm, who described the regulatory challenges facing AI start-ups in the field of healthcare, Professor Hiroshi Miyashita, speaking as a data privacy expert who examined emerging legal issues surrounding the nascent but rapidly growing field of neurotechnology and Dennis Tesolat, a spokesman for General Union, Japan’s largest labor advocacy group, who spoke about the increasing employer-employee conflicts due to the adoption of AI management systems by a growing number of Japanese companies.

Tokyo, Tuesday, January 14th – German Institute for Japanese Studies and TeamLabs

In the morning of the 14th of January, we visited the German Institute for Japanese Studies (DIJ) and held discussions with the Deputy Director of Sociology, Barbara Holhus, exploring the possibility of various short and longer-term collaboration avenues between DIJ, c:o/re and other Japanese universities. Having identified various research avenues of common interest, we agreed to meet regularly in the future. The trio of DIJ-c:o/re-APU brings a set of complementary competences to collaborate on the comparative study of research cultures and their technological evolution.

Later that day, before catching Japan’s famous Shinkansen highspeed train to our next destination, Kyoto, we took the opportunity of a mid-day hiatus to visit TeamLab Planets, an interactive museum providing customized AI-powered art experiences. Utilizing state-of-the-art technology, TeamLab Planets offers visitors seven different types of multi-sensory, fully immersive artistic environments. Not only did we all find this immersive experience very relaxing, we also noted how inspiring and motivating it can be, especially for the science and technology scholars.

Kyoto, Wednesday, January 15th – Kyoto University’s Disaster Prevention Research Institute and School of Informatics

On the 15th of January, we ventured to Kyoto University to meet researchers at the Disaster Prevention Research Institute (DPRI). Here we learned from various faculty members of the institute about the latest of current research developments in natural hazard reduction and integrated strategies utilizing the latest modeling software for disaster loss reduction. We were certainly surprised at the institute’s multidisciplinary embrace of artistic interventions in this regard, as a presentation by Naoko Tosa, a resident artist at DPRI, described her fascinating and thought-provoking designs in clothing fabric which weave digital sensors and actuators that are activated by cellular emergency warnings. Afterwards, we were invited to visit her studio, where we had a chance to get a closer look at the technical and conceptual aspects of her creative process in designing ‘disaster couture’.

The day concluded with a visit to the Department of Informatics at Kyoto University, where we met Professor Jaward Haqbeen, an Afghan AI researcher whose work focuses on the use of generative AI in language acquisition in developing countries such as Afghanistan and Nepal. We have discussed plans for future collaboration, particularly on matters of education, language learning and technological literacies.

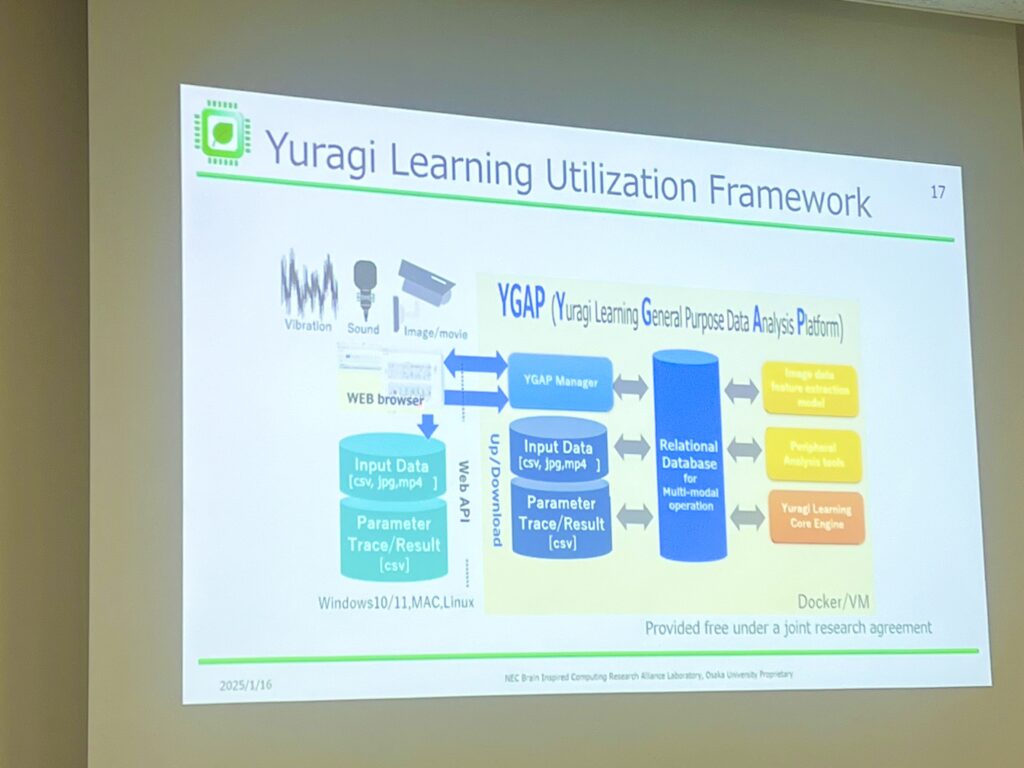

Osaka, Thursday, January 16th – NTT’s Brain Lab Osaka University

On Thursday, we headed to Osaka to visit one of Japan’s leading research centers for brain science, NTT’s Human Information Science Laboratory (HISF) at Osaka University. Employing a multidisciplinary approach to neuroscience, HISF brings together some of the nation’s top scientists from the fields of information science, psychology, and neuroscience. Utilizing cutting-edge technologies, HISF researchers study the mechanisms underlying human perception, cognition, emotion, and movement with a current focus on understanding how environmental and social information is processed in the human body and brain. These findings are expected to serve as basis for future information technologies that are conceptually new and user-friendly. During their presentation, we learned about technology development in a surprising way, especially about the “Yuragi-Group”. This group originally develops AI according to the unique cultural principle of Yuragi, which not only enables new technical options, but also allows specific value judgments to be realized (the topic of transparency of AI). They have arrived at a unique form of AI programming that differs from deep learning programs in relevant parameters. In this way, an element of transparency has been built into the AI, as the map of affordances (this is, so to speak, the cognitive system of the AI; our formulation) can be transferred to the next system in each case. It relies on a cultural repertoire and the formation of epistemic heuristics.

Beppu, Friday, January 17th – Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University

On Friday the 17th, the team along with Professor Masahiko Hara (Institute of Science, Tokyo) gave talks at Professor Mantello’s home institution, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in Beppu, located on the east coast of Kyushu Island in the south of Japan. Targeting a primarily undergraduate audience, Stefan Böschen gave an informative lecture on the importance of science and technology studies. Alin Olteanu engaged students with a talk on the semiotics of Digital Nomadism and Masahiko Hara on his experimental artistic interventions into intelligent interfaces that read human emotions.

Outlook

Like most countries, Japan and Germany share fundamental values such as freedom, democracy, and the rule of law. They also agree that accountability, transparency, human rights and privacy should be built into AI. Yet where the EU/Germany wants a top-down government-led approach to mitigate AI harms, Japan (at least at the moment) prefers an industry/sector approach to give the technology a good chance to grow. At the government level, the annual Japan/Germany ICT Policy dialog forum promotes the need for common rules on AI. Importantly, Japanese labor law is influenced by the German legal contexts. But while German law on AI in the workplace is becoming increasingly precise and restrictive, current Japanese law is vague and ambiguous. Thus, it is important to refer to the development of both EU and German law for comparisons of Emotional AI in the workplace. As Co-Investigator Hiroshi Miyashita argues, “Japan is well-known for importing foreign laws, but a patchwork of copy/paste does not work well in a Japan”.

Concomitantly, our collaborative efforts to date suggest that Japan could offer a third way by heuristically exploring the space of AI development that seeks to create harmonious human-machine relationships, with a focus on AI that preserves human dignity. Keeping this in mind, the journey goes on, and we look forward to further opportunities to collaborate with the project of Professor Mantello, as well as with the DIJ and other stakeholders from both the private and public sector. It is interesting to note that the Japanese government is fueling the evolutionary dynamic in the field by creating far-reaching exchange opportunities for incoming researchers.

Photo Credits: Peter Mantello

Posted on April 14, 2025 by Jana Hambitzer