Symposium: Critical Perspectives on the Metascience Reform Movement

The Käte Hambuger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re) is co-sponsoring the Critical Perspectives on the Metascience Reform Movement Symposium by the Center for Open Science, taking place virtually on March 7, 2024, from 9:30 am to 12:30 pm EST.

Metascience is often defined as the scientific investigation of science itself with the aim to improve science. This ‘improving’ part of metascience has been called a reform movement. While the intention to improve science is generally laudable, metascience and the associated movement(s) are not without their critics. The metascience reform movement has for instance, been characterized as, among other things, neoliberal, positivistic, atheoretical, technological, moralizing, bureaucratic, homogenizing, mechanistic, quantitative, psychological (psychologizing), social, civilizing, bullying, exclusive, coercive, activist, and normative. Some of those critical perspectives will be presented and discussed in this symposium.

KHK c:o/re Fellow Dr. Bart Penders will also contribute with a talk on “Shamed Into Good Science”. Symposium: Critical Perspectives on the Metascience Reform Movement

For additional information, including the program schedule and free registration, please visit the symposium’s webpage.

Get to know our Fellows: Bart Penders

Get to know our current fellows and gain an impression of their research.

In a new series of short videos, we asked them to introduce themselves, talk about their work at c:o/re, the impact of their research on society and give book recommendations.

You can now watch the fifth video of Dr. Bart Penders, PhD in Science and Technology Studies and Associate Professor in ‘Biomedicine and Society’ at Maastricht University, on our YouTube channel:

Check out our media section or our YouTube channel to have a look at the other videos.

Objects of Research: Erica Onnis

Today we continue our „Objects of Research“ series with a picture by c:o/re Alumni Fellow Dr. Erica Onnis, whose research focuses on the nature of emergent phenomena, and the relation between the notion of emergence and those of reduction, novelty, complexity, and causation.

“When asked about the fundamental object for my reaserch practice, I immediately thought of my computer, which seemed the obvious answer given that I read, study, and write on it most of the time.

Upon further reflection, however, I realized that on my computer, I just manage the initial and final phases of my research, namely gathering information and studying on the one hand, and writing papers on the other.

Yet, between these two phases, there is a crucial intermediate step that truly embodied the essence of research, for me: the reworking, systematization, organization, and re-elaboration of what I have read and studied, as well as the formulation of new ideas and hypothesis. These processes never occur on the computer but always on paper.

Therefore, the essential objects for my research are notebooks, sticky notes, notepads, pens, and pencils.”

Would you like to find out more about our Objects of Research series at c:o/re? Then take a look at the pictures by Benjamin Peters, Andoni Ibarra, Hadeel Naeem, Alin Olteanu, Hans Ekkehard Plesser, Ana María Guzmán and Andrei Korbut.

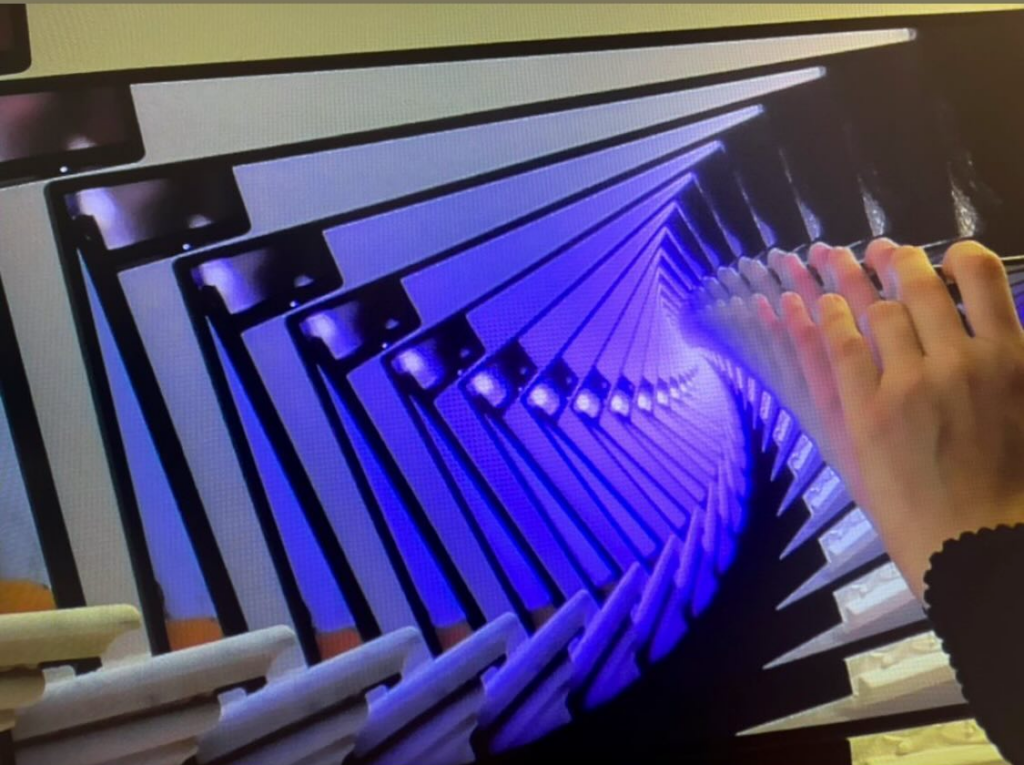

Unfelt Threshold: Art Installation at c:o/re

On 30 January 2024, the art installation “Unfelt Threshold” by the Japanese artist Aoi Suwa was opened at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re).

During the live performance of the installation and the following discussion with c:o/re Senior Fellow Masahiko Hara on “Fluctonomous Emergence”, the audience was able to experience how machines react to the unpredictable, unknown behaviour of materials, e.g. changing incidence of light. This is where Masahiko Hara’s research comes in, focusing on the integration of art strategies into science and technology based on the emergent functions of autonomous systems that exhibit fluctuant behaviour.

photo by Jana Hambitzer

In her project, Aoi Suwa is indirectly linking together various pieces and exhibits that she has produced over the years. The idea behind it emerged out of the concept of “shiki-iki” (識閾, lit. “threshold of consciousness”), which also informed Shiki-iki (Border, 2011), the first installation that Suwa formally presented to begin her career. Composed of a tank of water partitioned with a piece of clear plastic, the work was activated when the viewer poured ink into the water, producing a dynamic effusion of colour that gradually revealed the presence of the initially imperceptible boundary.

photo by Jana Hambitzer

Suwa has since continued to employ such experimental techniques to create works focused on phenomena that can only be witnessed in situ, developing what could be described as an approach aimed at perceiving thresholds that emerge through the process of traversing back and forth between the realms of the perceivable/imperceivable and conscious/unconscious.

Suwa’s approach can be likened to the way one might attempt to gradually visualize the orbit of a celestial body as it makes its periodic passes or a drawing as it takes shape through the iterative actions of marking and erasing. Through this project, she aims to explore its potential as a way of giving expression to the complexity of our current age, which eludes description in terms of simplistic binaries.

The installation can be viewed until 22 February 2024 by prior registration with events@khk.rwth-aachen.de.

Interview with Aoi Suwa

Could you please introduce yourself?

My name is Aoi Suwa. I come from Japan, Tokyo, I’m an artist and I’m also PhD student in fine arts at Tokyo University of the Arts. I’m mainly focusing on creating installation work like this, and I am also very interested in the relationship between Art and Science.

What is your installation about?

I named this work Patched Phase. It means that if we see something, something is not just one. It’s very complicated. So, we have a consciousness, but consciousness is also like a more complicated structure for me. I wanted to express such a structure. It is invisible, but if I see it, I imagine the subject’s chaotic dynamics shape it.

Where do you take your inspiration from?

My starting point was the elementary school student generation. When I was an elementary school student, I met a science teacher. She is a very nice person, and she showed me very interesting chemical reactions, the liquid colour is changing again and again. I am very surprised and I got some inspiration from chemical reactions.

I often get so many inspirations from chemical phenomena, natural phenomena in science fields. I very like science, but I mean, I want to see science. It’s very difficult to explain. But, this is the important thing. Of course, I want to understand science, but not only this, I want to feel science. So that’s why I often get some new inspiration from natural phenomena.

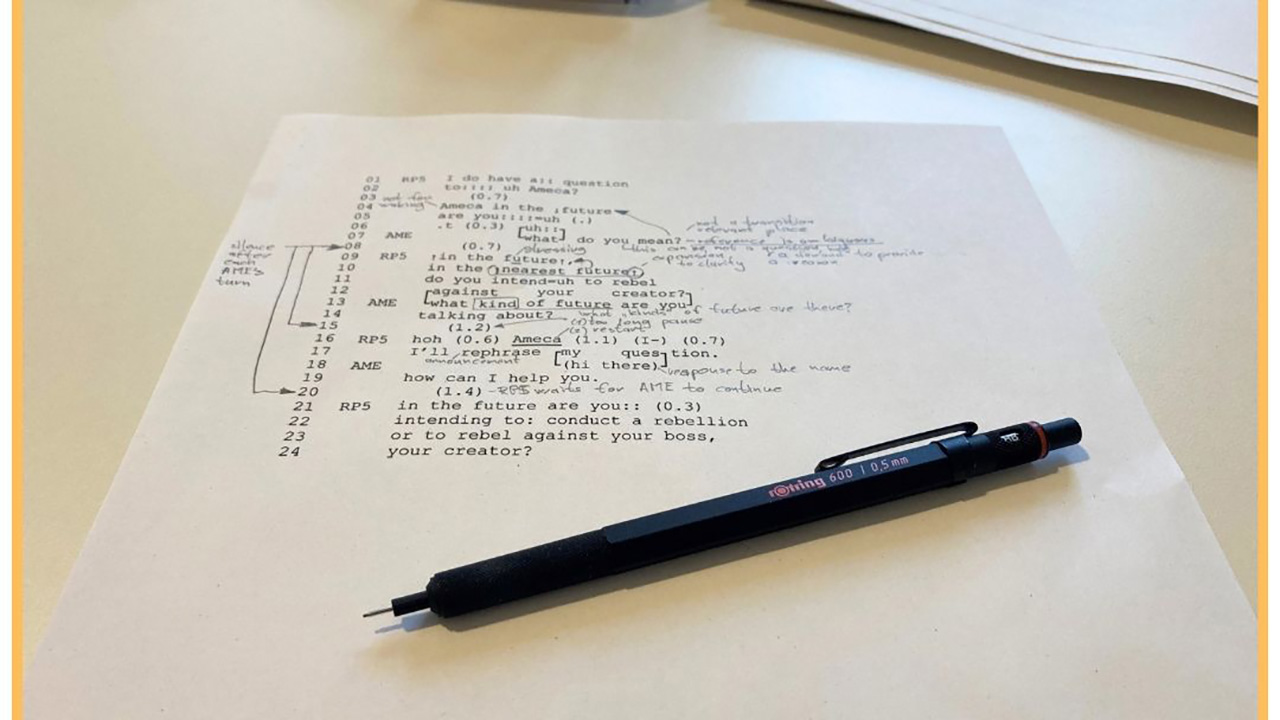

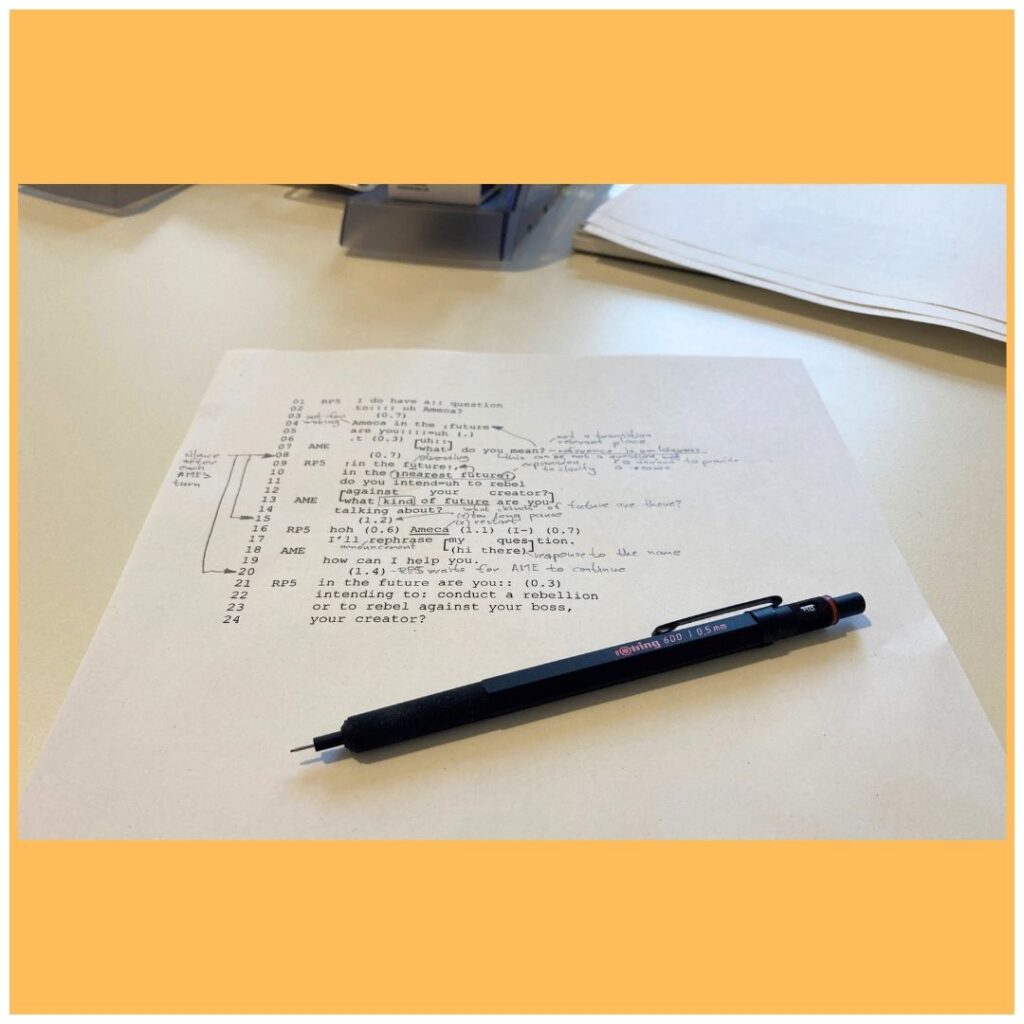

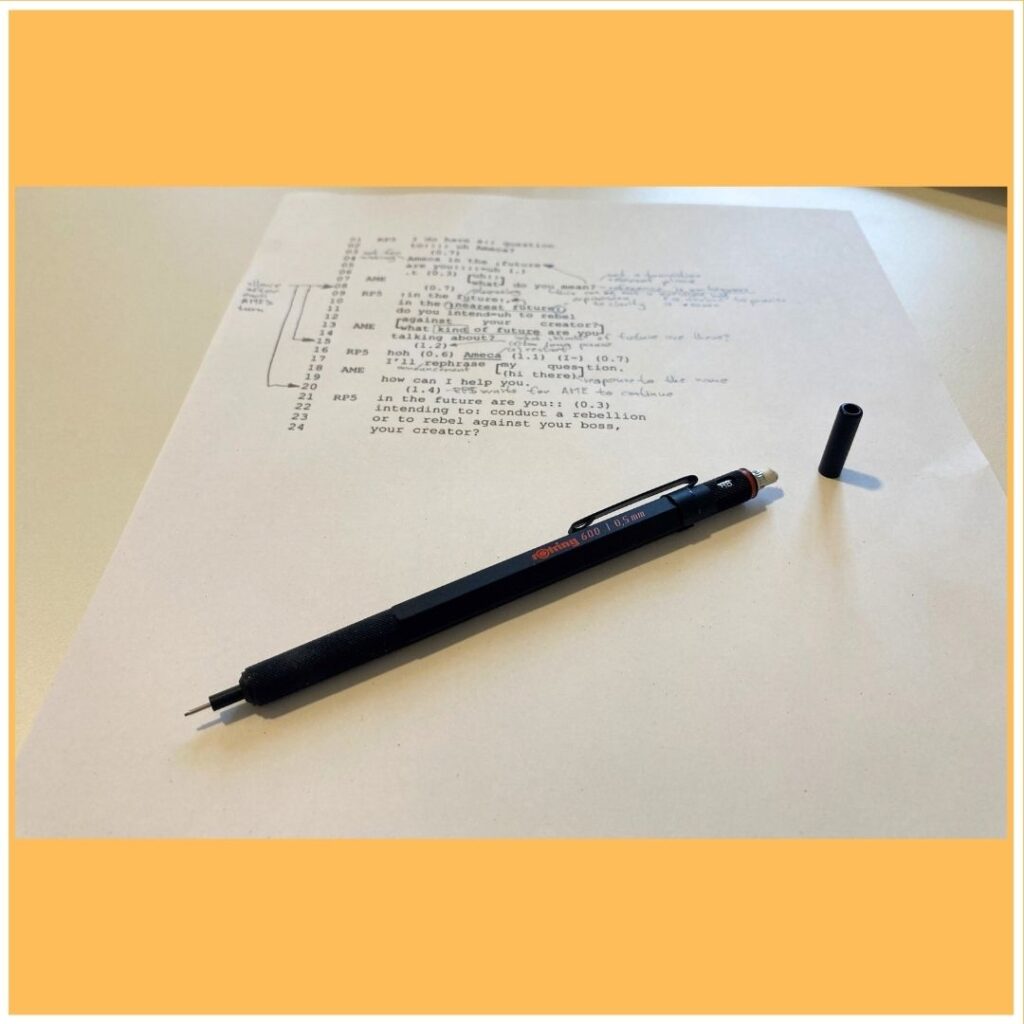

Objects of Research: Andrei Korbut

New edition of our “Objects of Research” series: Find out what c:o/re Junior Fellow Andrei Korbut‘s most important research object is. In his studies Andrei focuses on human–machine communication, applying ethnomethodology and conversation analysis to reveal the detailed ways in which humans organize their interactions with computers.

“There is a joke about which faculty is cheaper for the university. Mathematics is very cheap because all they need is just pencils and erasers. But philosophy is even cheaper because they don’t even need erasers.

My favorite and indispensable object is the rOtring 600 mechanical pencil. It shows that social science is closer to mathematics than to philosophy. Of course, social scientists often need more than pencil and eraser: they have to collect and process data from the real world. But this processing is greatly facilitated by the ability to write and erase your observations.

In my work, I deal with the transcripts of human-machine communication, and I use the rOtring 600, which has a built-in eraser, a lot. It’s useful not only because of the eraser, but also because it’s designed to stay on the table and not break, even in very demanding circumstances like the train journey. And it gives me the feeling that I am making something tangible with it, because it reminds me of engineers or designers producing blueprints for objects and machines.”

Would you like to find out more about our Objects of Research series at c:o/re? Then take a look at the pictures by Benjamin Peters, Andoni Ibarra, Hadeel Naeem, Alin Olteanu, Hans Ekkehard Plesser and Ana María Guzmán.

c:o/re Newsletter – Special Edition

As many exciting things have happened and will happen in the past and coming months, we would like to quickly update you with this special edition of the c:o/re newsletter.

We hope you enjoy it!

K. Jon Barwise Prize for

Gabriele Gramelsberger

Special honour for her research work: c:o/re director Gabriele Gramelsberger has been awarded the 2023 K. Jon Barwise Prize by the American Philosophical Association (APA).

The K. Jon Barwise Prize honours members of the APA who have made significant and sustained contributions to the areas of philosophy and computer science over the course of their careers. Gabriele Gramelsberger’s research focuses on the philosophy and epistemology of computer science. She has conducted extensive studies on modelling, simulation and machine learning in climate science and molecular biology.

From 16 to 17 May 2024, the KHK c:o/re will host a celebration workshop on “Epistemology of Arithmetic” by Gabriele Gramelsberger (Barwise Prize) and Markus Pantsar (book publication “Numerical Cognition and the Epistemology of Arithmetic” at Cambridge University Press in May 2024). Further information will be available here shortly.

acatech membership for

Stefan Böschen

End of the year 2023, c:o/re director Stefan Böschen was appointed as a new member of acatech, the National Academy of Science and Engineering.

The acatech membership recognises outstanding scientific accomplishments of the elected scientist, which contribute to acatech’s mission. acatech as a working academy aims at science-based advice to policymakers and society thereby linking technological developments to aspects of Transformation and Society. Areas of interest are energy and resources, mobility and logistics, life sciences and health, digital transformation, boundary conditions for innovation and transformation of the business location.

Art installation at c:o/re:

Unfelt Threshold

We are delighted to present the first art installation at KHK c:o/re.

The installation is a cooperation between Japanese artist Aoi Suwa and c:o/re Senior Fellow Prof. Masahiko Hara. On Tuesday, 30 January, the collaboration opened with a live art installation and conversation on Fluctonomous Emergence.

You are cordially invited to visit the installation until 22 February 2024. Please register by sending an email to events@khk.rwth-aachen.de. The installation is located in the back of our lecture hall at our building on Theaterstraße 75.

Research stay in New York

From 11 March to 5 April 2024, our postdoc Phillip H. Roth will be a visiting research fellow at NYU’s College of Arts & Science. His stay is hosted by Lisa Gitelman, a leading media historian working on American print culture, technologies of inscription, and the emergence of new media.

Phillip will be advancing his project on communication formats in late-modern science, specifically on the history of preprints in particle physics.

PoM in Aachen

From 22 to 26 April 2024, the experimental conference Politics of the Machines: Lifelikeness & beyond will take place in Aachen, which seeks to bring together researchers and practitioners from a wide range of fields across the sciences, technology and the arts to develop imaginaries for possibilities that are still to be realized and new ideas of what the contingency of life is.

As part of the conference, a cooperation with the Performing Arts Centre PACT Zollverein in Essen is planned for Friday, 26 April, and Saturday, 27 April 2024. With ›life.like‹, PACT invites you to an experiential, installative, and discursive journey that questions and transcends the boundaries between machines, objects, and biological systems. What spheres exist beyond the dividing lines of the living and non-living? How do data and unknown techno-social interactions influence decisions and our perception of the living? What relationships, realms of possibility, and collaborations emerge between technologies and artistic practices?

We look forward to seeing you there!

Marketplace Engineers at Work: How Dynamic Airline Ticket Pricing Came into Being

GUILLAUME YON

If you have recently been online looking up for flights, you may have noticed that prices for airfares are always in flux. But what online shoppers usually do not know is that these dynamic price changes are enabled by large and intricate technological systems powered by cutting-edge science and technology.

These systems were first deployed by airlines in the United States in the 1980s. Up until today, they have been an object of intense scientific and technological research and development. When deploying such systems in airlines at scale, engineers and scientists blend statistics and probabilities, mathematical optimization, computer science, and economics, all this to implement sophisticated business strategies.

Dr. Guillaume Yon

Guillaume Yon is a historian of economics, who researches and teaches how the ideas that shaped our economic thinking emerged. He is particularly interested in the economic knowledge produced by engineers working in industry.

In the talk I delivered at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg ‘Cultures of Research’ on December 13th, I focused on what is often considered as the first of these systems: DINAMO. DINAMO stands for dynamic inventory and maintenance optimizer. It was developed at American Airlines and was fully operational in 1988. Similar systems were implemented at other major airlines in the United States around the same time, and these systems came to be known to specialists as ‘revenue management’ systems.

What was the problem that American Airlines’ engineers had to solve? As the airline industry was being deregulated in the U.S. (a process completed in 1978), American Airlines’ marketing department came up with a new strategy, which had two connected components.

The idea was to offer multiple price points for the same seats in the same class of service on the same flight. At the time, aircrafts had two classes of service, first and coach. Coach was the second class and main cabin, as in trains in Europe these days, and less like today’s economy seats in airplanes. In coach, American Airlines’ flights were regularly departing half-empty, hence the idea, in order to fill up these empty seats and avoid the associated loss in revenue, to stimulate a new demand, coming from people travelling for leisure. Before deregulation, air travel was a luxury product, and American Airlines was not alone in thinking that there was an untapped and potentially huge new market out there: middle-class families going on vacation, college students coming back home, young couples going away for the weekend, senior citizens visiting their children and grandchildren. However, these new leisure travelers were price sensitive, hence the need for a price discount to attract them, and fill the empty seats.

The second component was to prevent American Airlines’ already existing business customers, who travelled in coach too, from buying at the discounted price. Business customers were less price sensitive than the new leisure travelers, as they traveled on company money. They were willing to pay more for the same seat in coach. If business customers could buy the discounted fare, the new strategy would only result in a new source of revenue loss, this time from the business travelers’ side. American Airlines’ marketing department came up with the idea to tie the discounted prices to restrictions. For instance, American Airlines Ultimate Super Saver, a fare launched in 1985, was cheaper than the full fare for the same seats in coach. However, it was available only up to 30-days before departure (the so-called ‘advance purchase requirement’), had a steep cancellation fee, and was available only to those buying a round trip ticket with a Saturday night stay. Business travelers could not abide to those restrictions. They tended to book later and wanted to spend the weekends with their families. Therefore, even though discounted fares were available for a flight, business travelers would carry on buying at a higher price the seats on the same flight.

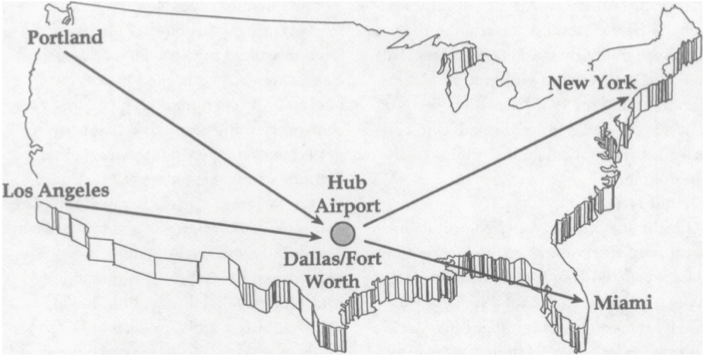

The outcome of American Airlines’ new pricing strategy was that for a given flight – from A to B, with a given departure date in the future – the seats in coach were offered at different prices with different restrictions (the lower the price, the more stringent the restrictions). These different ‘fare classes’ were available for sale at the same time. This new marketing strategy was a tremendous success for American Airlines, and it played an important role in turning air travel into mass transportation.

This tremendous success from a revenue perspective turned into a nightmare from a business process perspective. At American Airlines, hundreds of new revenue management analysts were hired, and they were struggling. Each revenue management analyst had a set of flights to manage. They needed to decide, for each flight, how many seats should be made available for sale in each fare class in order to obtain, at the flight departure, the mix of passengers which maximizes revenue. That decision needed to be made at first a year before departure, when the flight opened for booking. In the mid-1980s, there were at least three different fare classes in coach (the full fare, the Ultimate Super Saver, and a Super Saver in between), in addition to the first class, on each flight. Worse, American Airlines re-organized its network after deregulation as a hub-and-spoke, in order to efficiently serve more destinations domestically and internationally. Each path in the network with a connection at the hub also had at least three fare products in coach. For the local traffic, if the analyst allocated too many seats to the lowest fares, it could displace high paying business travelers. But allocating too few seats to the lowest fares could mean departing with empty seats, if high paying demand did not materialize late in the booking process. Simultaneously, for the same flight, the analysts needed to decide what the revenue maximizing mix of local and connecting traffic was. Was it best to have one more seat protected for a high paying business passenger on that flight, or have one more discounted passenger on the same seat but with a connection to a long-haul expensive flight? It depended on the price each of those two passengers paid, the likeliness of each passenger showing up for booking, and how full each of the two flights were. Humans could not possibly make all these decisions efficiently at scale. Therefore, around 1982/1983 American Airlines management tasked its operations research department with automating the process.

Source: Smith, Leimkuhler and Darrow (1992) ‘Yield Management at American Airlines’ Interfaces 22 (1), pp. 8-31.

To automate the process, operations researchers started thinking from the actual available technology: SABRE (for semi-automated business research environment). SABRE was big tech at the time. It was the first global electronic commerce infrastructure, allowing travel agents to sell tickets through a dedicated terminal, connected to American Airlines inventory in real-time, by telephone transactions. SABRE was also an amazing database, as it recorded the numbers of bookings for each fare class on each flight. However, for revenue management analysts, this deluge of data was overwhelming.

Source: IBM; https://www.ibm.com/history/sabre; Last Accessed Jan. 2024.

American Airlines’ engineers aimed at overcoming the limitations of human decision-making through automation. To do so, they needed to redesign SABRE, which was simultaneously an information system (or a database, recording bookings in each fare class at the flight level) and a distribution infrastructure (a marketplace). They asked: how to expand it, and turn it into a pricing system (able to manage which fares were available for sale on each flight from a network flow management perspective)?

The articulation of that problem is historically significant. American Airlines’ operations researchers sought to solve a business problem, the implementation of a sophisticated new pricing strategy, which aimed at making pricing more dynamic, more market-responsive, more granular. But they did not look for the theoretically optimal solution. Instead, they sought to deploy a new technology. To do so, they started from an already existing technology, identifying the constrains and opportunities it offered. This already existing technology (SABRE) was a global electronic commerce infrastructure, i.e. the marketplace itself, coupled with a large database on bookings, i.e. customers’ purchasing behavior.

I spent most of the talk narrating how American Airlines’ operations researchers came to a solution. I tried to show how their thinking was shaped by the details of the distribution infrastructure: how airlines’ products were sold to customers through a computerized system, i.e. the features of the marketplace itself. I also tried to show how their thinking was shaped by the data (availability and size) and the computing power they had access to.

I argued that the crucial step to the solution was nothing spectacular, just a hack in SABRE called ‘virtual nesting’. This hack enabled the management at the flight level of the availability of the connecting fare classes, when working with two new components plugged into SABRE. First, an automated demand forecast, powered by statistical and probabilistic approaches, extracted the historical booking data in each fare class in each flight from SABRE, and then provided an expected revenue for each ‘virtual bucket’ on a flight. The expected revenue of a bucket meant the average price of the range of fare classes clustered in the bucket, weighted by the probability of having that many customers booking in that bucket. Second, an algorithm allocated a number of seats to each bucket of fare classes, given the average expected revenue for each bucket; this component was called the optimizer. The mathematics supporting the optimization were not trivial. American Airlines’ operations researchers used mathematical programming approaches which belonged to the standard toolbox of operations research at the time. However, these tools needed to be creatively applied to the specific problem at hand, accounting in particular for the limitations in computing power. This required the development of completely new heuristics. Overall, using mathematical programming to make pricing more dynamic, more market responsive, and much more fine-grained than it had ever been before in any industry, was an important innovation. And it all hinged on a hack in SABRE.

DINAMO opened decades of intense research and development to improve the ‘hack’, the forecasting, and the optimization. The underlying logic is still in use today, at least in the largest networked airlines. It directly inspired marketplace engineers in many industries, from Amazon to Uber, from hotels to concert tickets sellers. It features prominently in the training of the future generation of marketplace engineers. And if your local supermarket uses digital price tags on the shelves, it is likely that they are using a version of it too.

Sources

The knowledge produced by marketplace engineers is not widely shared beyond the community of specialists. Furthermore, it is very practical and operational, and for that reason not fully codified in the scientific literature. Therefore, the main sources for my research are interviews with the engineers and scientists who built these systems in airlines (50 people interviewed so far, and the list is still open!). I asked them how they proceeded, the resources they had, the environment they were working in, what their thought process was, their path to the solution. My interviewees also walked me through the technical literature they have produced, in particular technical presentations delivered at an industry forum called AGIFORS, the Airline Group of the International Federation of Operational Research Societies. This talk on DINAMO drew on my broader research project, in which I study the practices, forms of reasoning, and ways of thinking of engineers and scientists who built revenue management systems in the airline industry, from the origins in the 1980s to today. On DINAMO, the interested reader can start with this great paper that was published by its three main inventors: Smith, Leimkuhler and Darrow (1992) ‘Yield Management at American Airlines’ Interfaces 22 (1), pp. 8-31.

Proposed citation: Guillaume Yon. 2024. Marketplace Engineers at Work: How Dynamic Airline Ticket Pricing Came into Being. https://khk.rwth-aachen.de/2024/01/31/9192/marketplace-engineers-at-work-how-dynamic-airline-ticket-pricing-came-into-being/.

Get to know our fellows: Andrei Korbut

Get to know our current fellows and gain an impression of their research.

In a new series of short interviews, we asked them to introduce themselves, talk about their work at c:o/re, the impact of their research on society and give book recommendations.

1. Please introduce yourself.

I’m Andrei Korbut. I’m a sociologist studying human-computer interaction.

2. What is your research about?

My research is about how a particular kind of humanoid robot — it’s called Pepper — has become a popular research tool in robotics labs around the world.

I want to understand what properties of the robot make it useful for studying human-robot interaction, and how it is embedded in and helps to produce the configurations of epistemic practices, industrial interests, and academic politics specific to the field of robotics. To do this, I am tracing Pepper’s career from the production line to publication in an academic journal.

3. How do you see your research impact society?

I see the impact of my research as twofold. First, I hope that the results will influence policy decisions about science. There is a lot of talk about AI regulation nowadays, and as robotics is closely related to AI (although they are different fields), policymakers need more real-world knowledge about how robotics is organised to make their decisions more knowledge-based. And second, it would be great if my research could make humanoid robots less “opaque” to ordinary people. There is a lot of hype around humanoid robots today, based on developers’ desire to make them look more capable and autonomous than they really are. I think my research can show that these machines are not something supernatural and approaching humans in their abilities, but only exist because the large amount of human labour and knowledge is constantly embedded in them.

4. What does a research day at c:o/re look like for you?

I would even say that there is not one day, but two different days at c:o/re. The first is very quiet: I just go into the office and work at my desk, making notes, analysing data, reading, with some breaks for food and occasional conversations with colleagues. The second is more lively, full of discussions, meeting new people, and visiting very exciting places like real labs at RWTH. I like both days equally because they are beneficial for my research, although in different ways.

5. What does Cultures of Research mean to you?

For me c:o/re is a community of very talented and interested people where I can freely discuss my findings and plans and get new insights after each of such discussions. Small group of scholars working in the same field, as in c:o/re, is an excellent habitat for nourishing your ideas.

6. What book have you read recently that you would recommend?

It is a book not from my main area of interest, but I really enjoyed it. (I find it important to read outside my field from time to time.) It’s Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World by Marcia Bjornerud. This is a fascinating introduction to the way geologists think of time, providing some basic knowledge about the history of the discipline and the structure and evolution of the Earth. More importantly for me, the book teaches how to see the traces of time in the objects around us. The book is aimed at people like me who are not very familiar with geology, so I found it really interesting, not least because Bjornerud presents geology through her own personal experience as a field researcher. Also, the illustrations by Haley Hagerman are masterful.

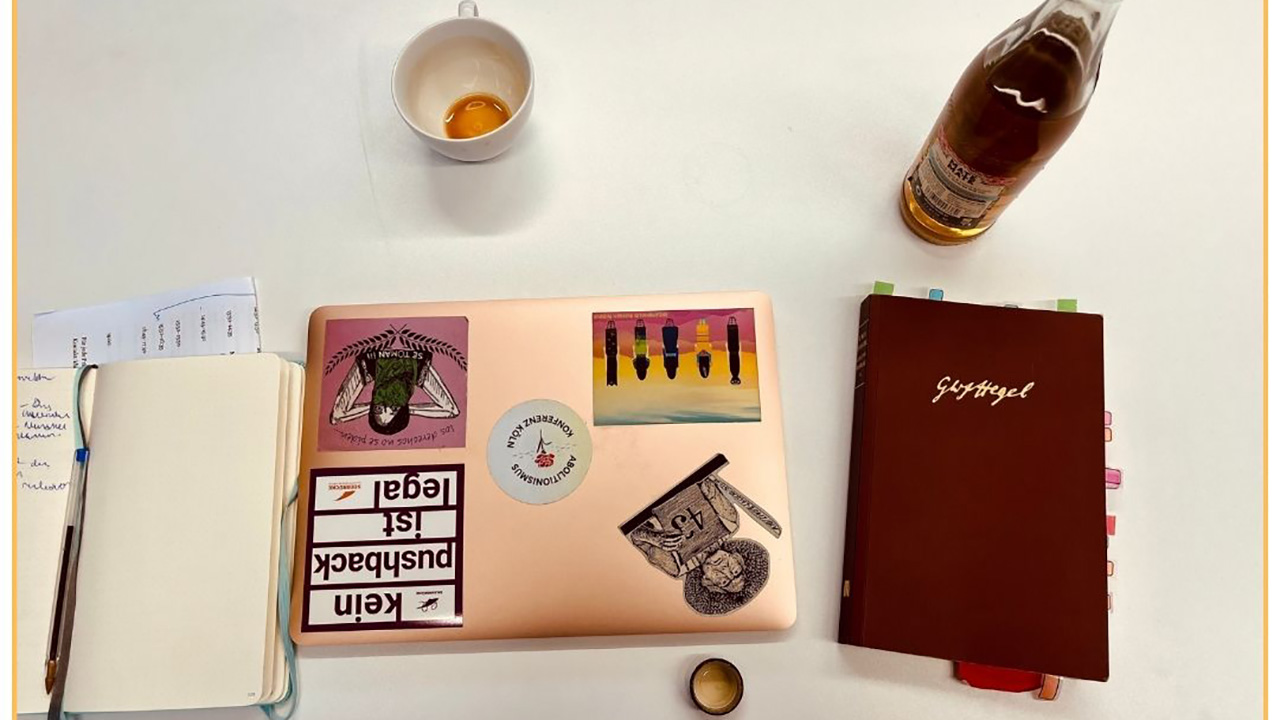

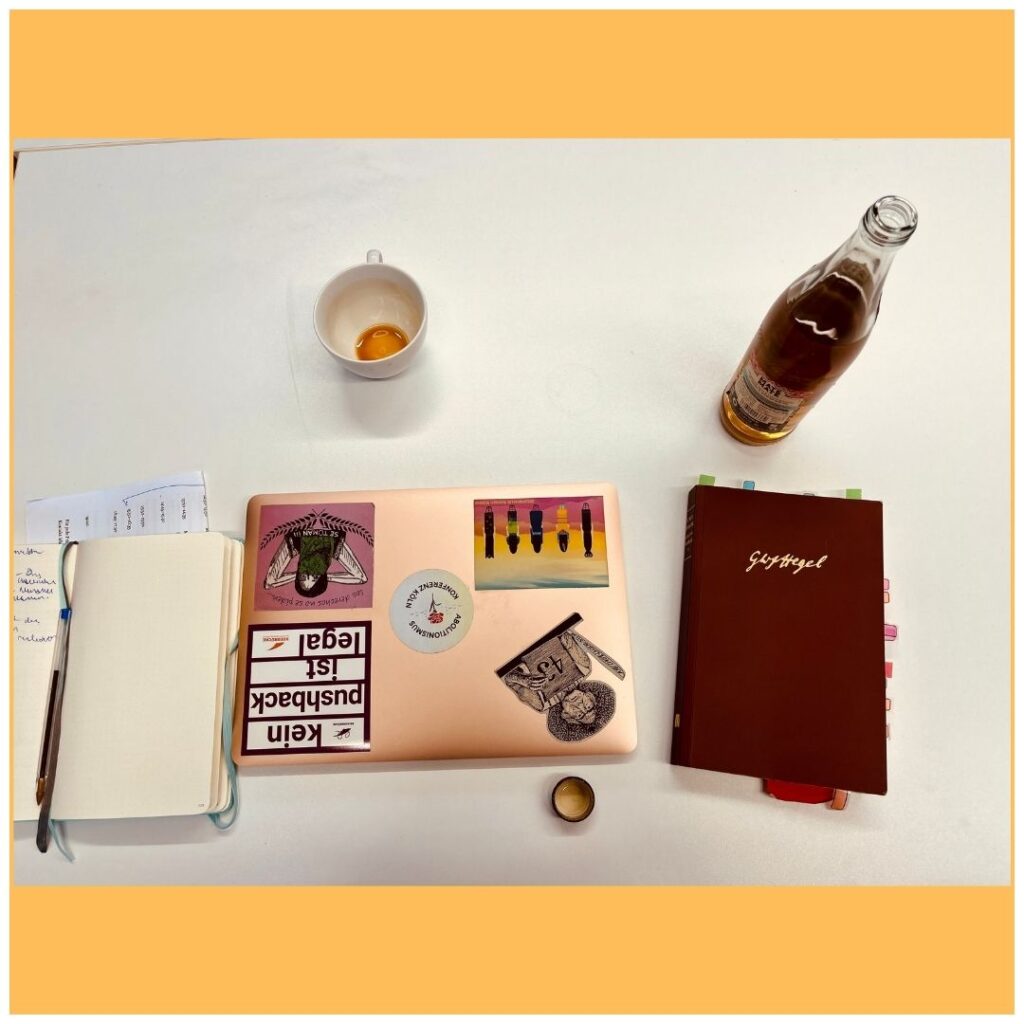

Objects of Research: Ana María Guzmán

Today we proceed our “Objects of Research” series with a picture by c:o/re research associate and events coordinator Ana María Guzmán, whose dissertation “Within Nature: Hegel’s Local Determination of Thought” deals with the conditions for the intelligibility of nature within Hegel’s Logic and Philosophy of Nature.

“As I research Hegel’s logic and how he understands life as a logical category necessary to make nature intelligible, I work closely with his texts. On the other hand, the stickers on my laptop remind me of the need to look at reality and regularly question the relevance of my research for understanding current social phenomena. In this sense, I think I remain a Hegelian, because for Hegel one can only fully understand an object of research by looking at both its logical concept and how it appears in reality. However, I think that in order to look at current political and social phenomena, we need to go beyond Hegel’s racist and sexist ideas, which are all around his ideas on social organization. And none of this would be possible without a good cup of coffee and/or a club mate!”

Would you like to find out more about our Objects of Research series at c:o/re? Then take a look at the pictures by Benjamin Peters, Andoni Ibarra, Hadeel Naeem, Alin Olteanu and Hans Ekkehard Plesser.

Peter Mantello

c:o/re short-term Senior Fellow (11/02 − 17/02/2024)

Peter Mantello is an artist, filmmaker and Professor of Media Studies at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in Japan. Since 2010, he has been a principal investigator on various research projects examining the intersection between emerging media technologies, social media artifacts, artificially intelligent agents, hyperconsumerism and conflict. His recent research focuses on interdisciplinary inquiries into phenomenological aspects of human-machine relations, especially, those related to emotional AI. He is also working on a feature film that deals with social, political, and cultural concerns surrounding the rise of emotional AI on six continents.

A Comparison of Views on Emotional AI in Japan and Germany

This research project examines the impact of emotional AI (EAI) in the Japanese and German workplace (on-site, hybrid, gig, and platform), to understand how to create ethical, human-centric, and dignity-enhancing forms of work practices and governance. Employing a mixed methods approach involving interviews, surveys, and innovative design-fiction and policy workshops, the project has five main goals. First, to understand the determinants of technological trust and risk perception of workers toward a new technologically mediated work situation. Second, to cultivate a nuanced understanding of the importance of cultural diversity in AI ethics by exploring the epistemological and ontological dimensions of emotion-sensing technologies. Third, to flesh out potential best practices so that these systems support rather than exploit workers. Fourth, to enable cross-cultural knowledge exchange (Japan/German) between academics and stakeholders. Fifth, to mentor the next generation of Early Career Researchers into leadership roles pertaining to AI ethics and the emerging world of emotion-recognition technologies.

Publications (selection)

Mantello, Peter, Ho MT, Nguyen, M. & Vuong, Q. 2023. Machines that feel: Behavioral determinants of attitude towards affect recognition technology—Upgrading technology acceptance theory with the mindsponge model. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 1-16. Nature.com https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01837-1

Mantello, Peter, Ho MT. 2023. Emotional AI and the Future of Wellbeing in the Post-Pandemic Workplace, AI and Society, Springer Nature. DOI: 0.1007/s00146-023-01639-8.

Mantello, Peter, Ho MT, Podoletz, L. 2023. ‘Automating Extremism: Mapping The Affective Role of Artificially Intelligent Agents in Online Radicalisation’ in E.Pashentsev’s, The Palgrave Handbook of Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence, Palgrave McMillan. ISBN: 9783031225512

Mantello, Peter, Manh, T. Vuong.Q. 2021. Bosses without a Heart: A Bayesian analysis of socio-demographic and cross-cultural determinants of attitude toward the Automated Management, AI & Society. Springer Nature. DOI: 10.1007/s00146-021-01290-1.

Mantello, Peter. 2021. Fatal Portraits: The Selfie as Agent of Radicalization, Sign Systems Studies, Tartu University Press, 2021 https://doi.org/10.12697/SSS.2021.49.3-4.16