On May 5-6 the second c:o/re workshop Varieties of Science took place. While the first workshop (Patterns of knowledge) of this series was hosted by the National Autonomous University of Mexico and focused on decolonizing STS, this second workshop addressed some Unexpected varieties, namely the diversity within European philosophy and science traditions. The event was hosted by the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Bucharest.

The event took off with Vice-Dean Andrei Marasoiu warmly welcoming the participants to the Faculty of Philosophy and explaining how the rationale of the Varieties of Science workshops is approached at this particular event, in light of the common interests on philosophy of science of c:o/re and the Department of Theoretical Philosophy in Bucharest (see Pârvu, Sandu, Toader 2015).

Before diving into the talks, as a main concern under the Varieties of Science theme, we were happy to listen to Dr. Andreea Popescu‘s announcement that the Association of Women in Philosophy in Romania is about to be established. Information on this Association will be available on the c:o/re website as soon as it is launched.

The common thread throughout talks spanning over two days was the concept of observation.

c:o/re director Professor Stefan Böschen delievered the first talk of the workshop, introducing the broad concept of Varieties of Science, in particular consideration of philosophical inquiry, wherein varieties of schools particularly abound. The notion, as propposed by Böschen (see Böschen et al. 2020), relies on Ulrich Beck’s (2006) Varieties of Capitalism, which addresses cosmopolitization in a dialectics of homogenization and heterogenization. Böschen remarked the effects of the “different anchors” for doing philosophy of science in different places. This led to considerations on epistemic truths and epistemic injustice, validity of knowledge, matters of representation and science communication and politics. By asking how can different formations of society be analysed in their peculiarity and relationality within the perspective of cosmopolitisation, Böschen proposes theorising processes of globalisation in awareness of “the other in the midst”. In this talk, he pointed to the importance of making premises visible and critically analysing one’s own presumptions under others’ views.

The second talk, delivered by Professor Constantin Stoenescu, addressed the dialogue between a Japanese culturally-based model of knowledge and Western philosophy. The foci fell on knowledge conversion and scientific ethos. Stoenescu presented Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) theory, coming from a post-Kuhnean tradition, on the passage from ‘knowledge‘ to practice based tacit know how. He followed the notion of “paradigm as interdisciplinary metrics” and developed a criticism of the reduction of knowledge to merely semantic information. Following scholarship from a Japanese context (e.g., Nishida 1970; Shimizu 1995, Nonaka, Konno 1998), Stoenescu proposed an approach to epistemic variation through the Japanese concept “Ba“, which, for lack of a better option, can be imprecisely translated to English as “place”. From this vantage point, he explained, knowledge is understood as resource.

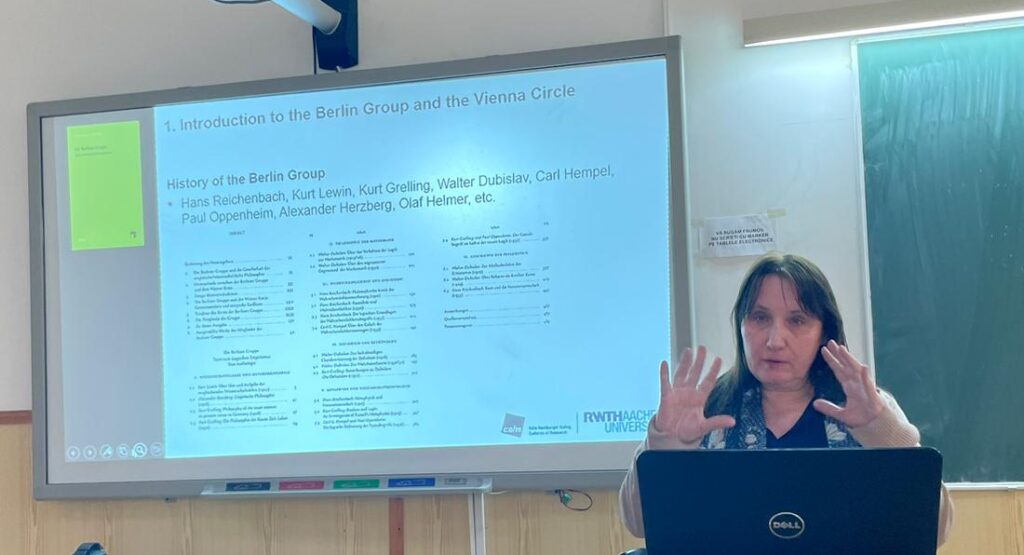

c:o/re director Professor Gabriele Gramelsberger offered an encompassing and insightful historical and comparative study of the Berlin Group and the Vienna Circle. She traced and, thus, highlighted the remarkable impact of the the Berlin Group for philosophy of science, which have been all too easily overlooked. She observed the shared views and the differences between these two groups, as illustrated to begin with, by logical positivism in Vienna and the logical empiricism (observatism) in Berlin. Both these groups, Gramelsberger, explained shared the destiny of “emigration, disintegration and new beginnings”, as they had to seek safety in the USA, given the coming to power of social nationalism in Germany in the 1930s. Because of its location, the Berlin group was more fiercely persecuted, which is one possible explanation for the enduring lack of awareness of its importance.

Gramelsberger identified three varieties by looking at these groups, roughly summarized here as:

- The comparative approach of the Berlin group, interested not only in empirical sciences, but also in analyzing theoretical sciences and mathematics;

- A focus on the role of theory of probability and logic;

- The pathway to Wittgenstein’s linguistic turn.

This exploration led Gramelsberger to remarking the linkages between early analytic philosophy and Gestalt theory, with possible connections also to phenomenology. As a conclusion and programmatic future work to be undertaken at c:o/re, Gramelsberger hypothesized on Paul Oppenheim’s Dimension of knowledge (1957) as overlooked by scholarship in this pathway of intellectual history.

The next two talks were delivered by the invited guests, Professor Gabriel Sandu and Professor Alexandru Baltag, who drew the focus of the workshop more closely towards analytical approaches. Main points of departure in their talks were Lewis’ (1973) reduction of causal relationship to counterfactual dependence and and von Wright’s (1976) manipulationist counterfactuals.

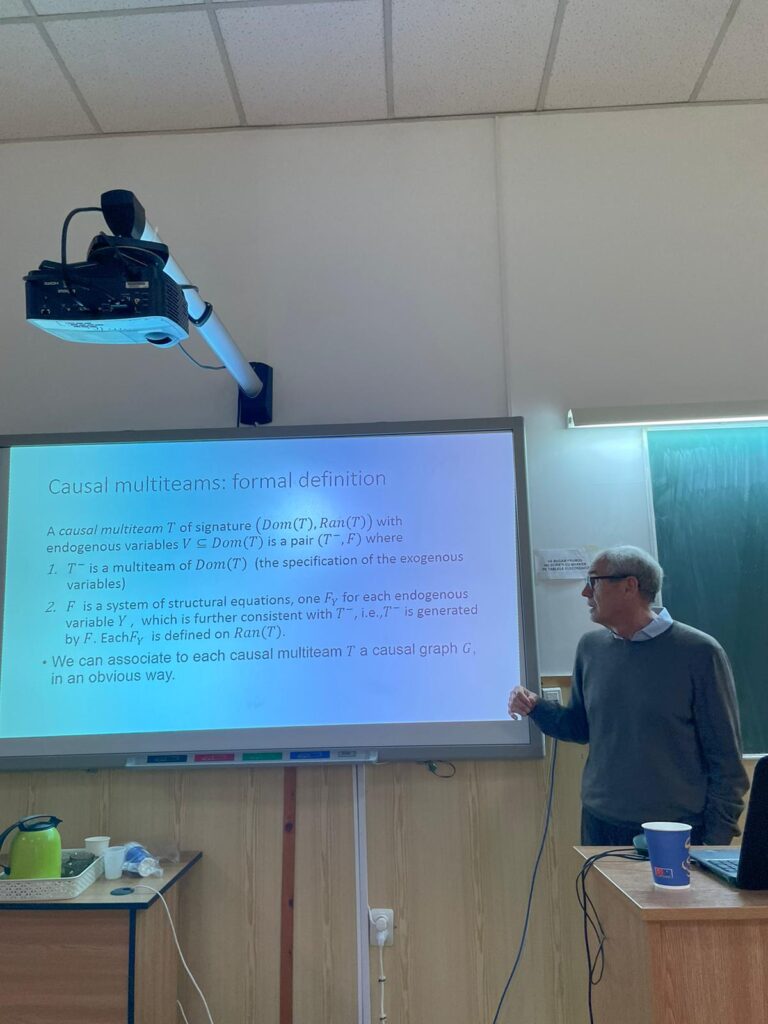

Gabriel Sandu proposed A logical framework for interventionist counterfactuals. Here, a causal relationship is considered to sustain a counterfactual assumption expressed thus: “on occasions where p, in fact, was not the case, q would have accompanied it, had p been the case”. A detailed and highly insightful discussion on possible worlds (Pearl, McKenzie 2018), led Sandu to advocate the notion of multi-teams.

Alexandru Baltag’s talk was titled The dynamic logic of causality: from counterfactual dependence to causal intervention. Starting Pearl’s causal models as the standard/dominant approach to representing and reasoning about causality, Baltag set of to (1) argue that interventions are dynamic modalities, (2) elucidate the relationship between dynamic intervention modalities and counterfactual conditionals and (3) formalize Causal Intervention Calculus. In his view, one should think of interventions, not necessarily as “actual” actions (that may happen in a given world or model), but as counterfactual actions, namely abstract manipulations of the causal structure, that happen to the model (world).

Dr. Markus Pantsar, a c:o/re alumnus fellow and current guest professor at RWTH Aachen, talked on Recognizing artificial mathematical intelligence (see Pantsar 2023). He asked, if AI were developed, how would we be able to recognize it (see Hernández-Orallo 2017)? To answer this question, Pantsar drew on parallels between research in animal intelligence and in aritifical intelligence. These parallels present two types of pitfalls: (1) the false negative that non-human animals have a particular type of intelligence, but we cannot observe them (experimental setting); (2) the false positive of supposing an “accumulator” mechanism instead of arithmetic. From here, Pantsar drew analogies to AI research, making several points, namely that: success in AI does not come down to theorem solving anymore; artificial neural networks are trained with huge amounts of data, and they “learn” statistical connections in the input, given that we have clear criteria for acceptable outputs; mathematics is not a success story of machine learning research, but this might change in the future; the problems of trying to figure out what happens in the hidden layers of the neural network (explainable AI). Pantsar shed light on what these issues have in common by citing the Zulu folk wisdom that “a person becomes a person through other persons”.

The second day of the workshop started with Dr. Dawid Kasprowicz‘ talk, Measurement problems need a consciousness: The case of Fritz London and the relation of Phenomenology to Philosophy of Science. Through a detailed study case on Fritz London (London, Bauer 1939), Kasprowicz tackled the question of how should a deductive theory look like, from a joint phenomenology and philosophy of science perspective (see also Alves 2021)? This opened an in-depth study on observation, the beginning of statistics in physics and the interrogations on observation as intervention that quantum theory produced.

In his talk, A free logic of fictionalism. On failed reference in meaningful discourse, Professor Mircea Dumitru unfurled an insightful criticism of Millianism, the doctrince that in propositions names contribute only to reference. His argumentation points in the direction of Kit Fine’s semantic relationism (see Dumitru 2020). This involved a minute and critical consideration of Sainsbury’s (2005) theory of reference and advocating a historicisation of philosophy of language that suggests the need for an alternative to the mainstream framing of philosophy of language within what is identified as a Fregean-Millian polarisation.

Sonja Smets‘ talk amusingly and wittingly suggested that Logic meets Wigner’s Friend(s): the epistemology of quantum observers. It encompassed an original discussion on the Heisenberg-von Neumann cut, namely the hypothetical interface between quantum events and an observer’s knowledge, in light of the Wigner’s Friend though experiment. In the consideration of observation in experiments, Smets was led to posit a notion of systems as agents and as leaking. She argued that systems can be treated as agents if only if they preserve information.

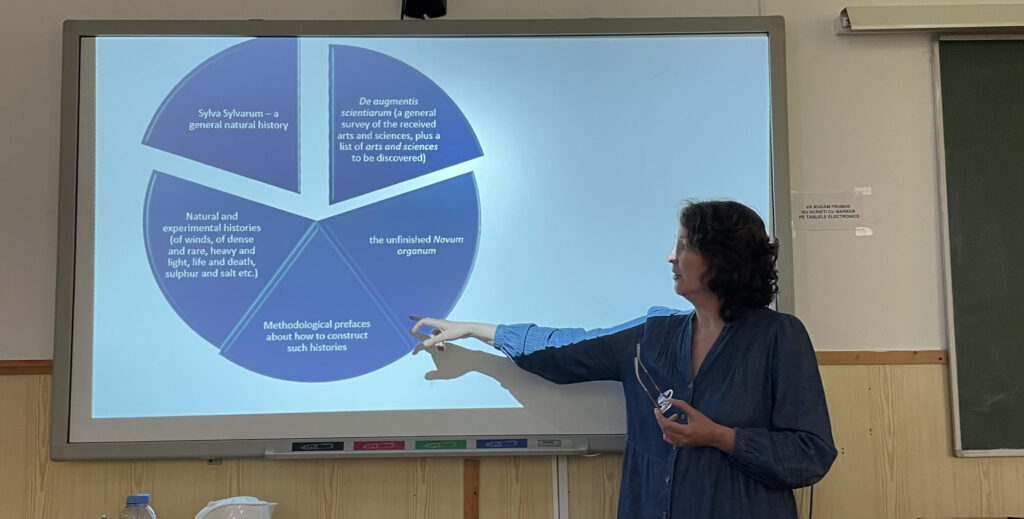

Professor Dana Jalobeanu proposed a reading of Francis Bacon’s programme for sciences through the heuristics of the fable genre. This reading of Bacon was particularly, but not only, illustrated through reflections on the figure of Salomon’s House in New Atlantis (see Bacon 2000).

Her talk, entitled The fable of science: Francis Bacon’s Solomon’s House and its European reception, shed new light on the history of early modern philosophy, particularly on how (early) modern programmatic narratives of science were rhetorically constructed so to produce the revolution that modernity came to be.

Dr. Arianna Borelli discussed Magic and Machines in the European Renaissance (see Borrelli 2023). She tackled this subject by taking Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633) as a case study, who built a perpetual movement machine (see Keller 2011). Through this investigation, she problematised the notion of (a modern) “scientific revolution” by revealing the heterogeneity of varieties of science in early modernity. She argued that Drebbel’s perpetuum mobile could have offered a starting point for reflection on science as good as automata or chemical reactions. While it might have led to the emergence of new fields of knowledge, mechanics and chemistry took the main stage of sciencein the 17th and 18th century, which led to the marginalisation in scientific inquiry of the phenomena at the centre of Drebbel’s work.

Benjamin Peters examined the material media philosophies of Soviet artificial intelligence research and its precursors, especially the sometimes anthropomorphic, sometimes invisual assumptions at work in the making of smart technologies (further and critically developing scholarship such as Graham 1987, Chun 2021). Through this talk he laid, out in ten clearly defined steps, his c:o/re fellowship project.

References

Alves, P.M.S. 2021: Fritz London and the measurement problem: a phenomenological approach.Continental Philosophy Review 54: 453-481

Bacon, Francis. 2000. A Critical Edition of the Major Works, edited by Brian Vickers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Borrelli, A. 2023. Aristotelianism, chymistry and mechanics in early seventeenth-century Europe. The techno-magical approach. In Verardi, D. Ed. Aristotelianism and Magic in Early Modern Europe: Philosophers, Experimenters and Wonderworkers, pp. 105–44. Bloomsbury Academic.

Beck, U. 2006. Cosmopolitan Vision. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Böschen, S., Hahn, J., Krings, B.-J., Scherz, C., Sumpf, P. 2020. ‘Globale Technikfolgenabschätzung’? Konvergenzen und Divergenzen kosmopolitischer Wissenschaftsdynamiken. In: Soziale Welt, Sonderband 24, p. 332-365.

Chun, W. H. K- 2021. Discriminating data: Correlation, neighborhoods, and the new politics of recognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dumitru, M. (Ed.). 2020. Metaphysics, meaning and modality: Themes from the work of Kit Fine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Graham, L. R. 1987. Science, philosophy, and human behaviour in the Soviet Union. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hernández-Orallo, J. 2017. The Measure of All Minds: Evaluating Natural and Artificial Intelligence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keller, V. A. 2011. How to Become a Seventeenth-Century Natural Philosopher: The Case of Cornelis Drebbel (1572–1633). In Dupré, S., lüthy, C. Silent Messengers: The Circulation of Material Objects of Knowledge in the Early Modern Low Countries, pp. 125–52. LIT Verlag.

Lewis, D. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

London, F., Bauer, E. 1939. La théorie de l’observation en méchanique quantique. Hermann Éditeurs.

Nishida, K. 1992 [1970]. An inquiry into the Good. Trans by Abe, M. and Ives, C. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nishida, K. 1970. Fundamental Problems of Philosophy:The world of Action and the Dialectical World. Tokyo: Sophia University.

Nonaka, I., Konno, N. 1998. The concept of “Ba“: Building a foundation for knowledge creation. California Management Review 40(3): 40- 54

Oppenheim, P. 1957. Dimensions of knowledge. Revue Internationale de Philosophie 40(2): 151-191.

Pantsar, M. 2023. Developing Artificial Human-Like Arithmetical Intelligence (and Why). Minds and Machines. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-023-09636-y

Pârvu, I., Sandu, G., Toader, I.D. Eds. 2015. Romanian studies in the philosophy of science. Cham: Springer.

Pearl, J., McKenzie, D. 2018. The book of why. The new science of cause and effect. London: Penguin Books.

Sainsbury, R.M. 2005. Reference without referents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shimizu, H. 1995. Ba-Principle: New Logic for the Real-time Emergence of Information. Holonics, 5(1): 67-69.

Wright, G. H. von. 1976. Causality and determinism. New York: Columbia University Press.

One Comment on “Varieties of Science 2. European traditions of varieties of science: Unexpected varieties”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback: c:o/re Highlights of 2023: A look back