ROBIN HILL

The Turing Test (the target of a great deal of attention) has three participants, including, in the standard version, a human foil who, along with the computer system, is hidden from the judge. Even in the extensive and intensive commentary on the Turing Test, I see no inquiry into the remit, or instructions, given to that hidden human HH. Presumably, HH is supposed to act natural in text exchanges. But there’s nothing natural about this scenario. The judge will try to manipulate the two hidden entities with personal or provocative questions and tasks. Does HH answer personal questions or refuse to answer? Does HH solve mathematical puzzles or dismiss them as silly? Can HH simply sulk, or take a nap, and refuse to answer at all? Insofar as HH is supposed to “act like a human”, how is that done? Can HH lie? Most salient, does HH have an objective in the TT; that is, can HH win or lose?

Robin Hill

c:o/re short-term Fellow 08/12 − 23/12/2025

Dr. Hill is a lecturer in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and affiliate faculty member in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, at the University of Wyoming. Her research interest is the philosophy of computer science, on which she writes a blog for the online Communications of the ACM, with several pieces published in the print edition.

If the practice differs across TT attempts, then there is no conscientious test taking place. An upcoming sub-conference called “Is there still life in the Turing Test?” raises such questions, in accordance with Turing’s original description of the TT, both explicit and extrapolated. This meeting will be held at the 2026 convention of the UK Society for the Study of Artificial Intelligence and the Simulation of Behaviour, July, University of Sussex. See the web page for submission information (due date in March).

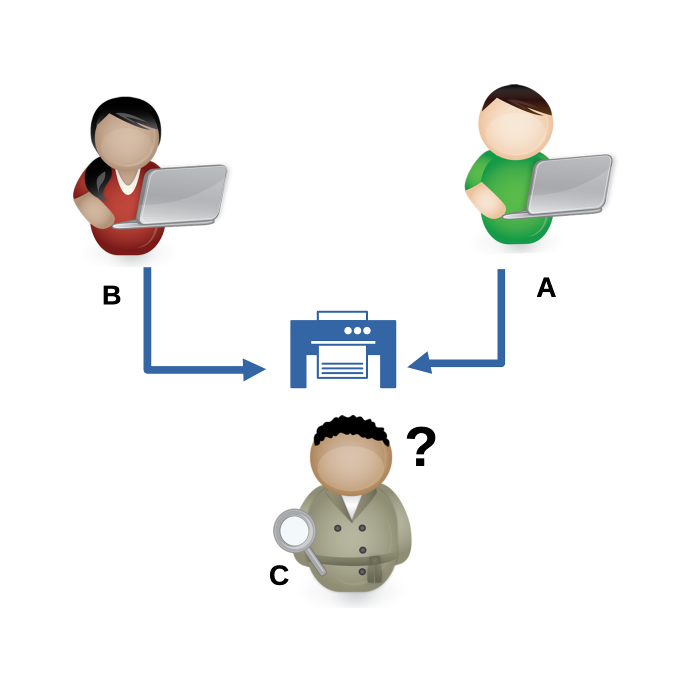

In the original paper, Turing starts by describing a party game in which a man (A) and a woman (B) are hidden from an interrogator (C) and both try to convince C that they are the woman. Parties A & B can see each others’ contributions, according to some readings, which implies either 1) Collusion – they are a team; OR 2) Competition – they are adversaries in a game.

It must be (2), because in the 1950 paper, the woman B helps the interrogator C while the man A tries to fool C into thinking that he is the woman. Presumably, Turing considered this scenario to make enough sense that the objectives were clear. Some interpretations, including that of the TT meeting, allow both A and B to see each other’s text.

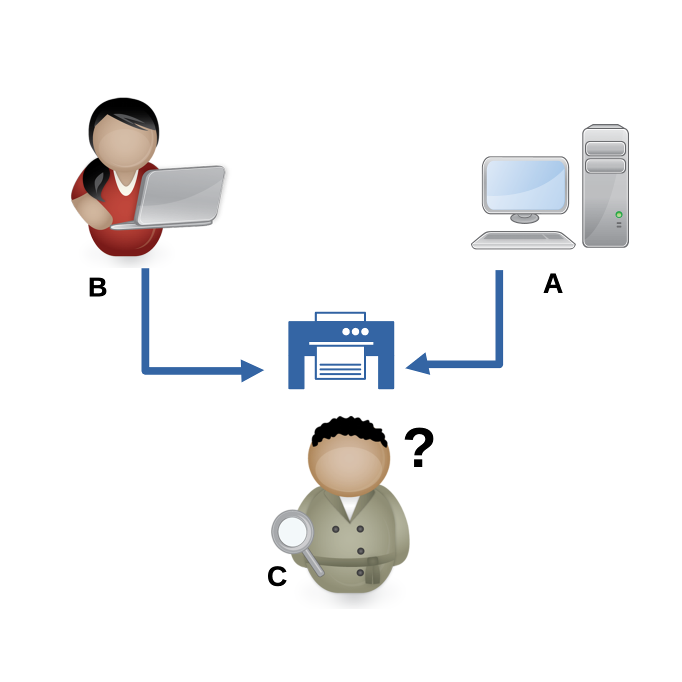

Then Turing changes the scenario: A becomes a computer and B (for whom no substitution is made) becomes the woman HH. We assume that B knows this substitution has taken place, and that her task is now to convince C, helpfully, that she is not a female human, but just human. According to Turing 1950, “the best strategy for her is probably to give truthful answers.” As for the computer, “it will be assumed that the best strategy is to try to provide answers that would naturally be given by a man.” So both are supposed to “act human” – unless, presumably, some other strategy on the part of B (HH) appears to be better for convincing the interrogator of her humanity. Consider the situation: Telling the truth in detached objectivity is not going to get her anywhere; in fact, that would be the completely neutral strategy, rendering B’s contribution superfluous. If the interrogator C does not already know how a human would respond, C is not going to gain much from B’s responses. The whole question, after all, is whether A is human. In other words, B needs to figure out (if taking her remit seriously), how to thwart A. If she observes A’s responses, then she can pick it apart. Perhaps if B is not allowed to see A’s responses, she can have a computer at hand for tests. But Turing did not seem to think that this was a demanding role; he seemed to assume polite cooperation. We might have to leave Turing, along with his vision, behind, because any sort of objective assigned to B will lead to maneuvers.

A Suggestion: Let’s ask some GPT chatbot about this.

Q1. “What would you do if you were playing the part of the computer trying to act human? Would you generate no response? Would you behave in some other antisocial way?

Q2. “What would you do, if you were the woman attempting to convince the interrogator of that fact? Would you attempt some uber-response to simulate HH (begging, observing, critiquing, etc.)?”

This author has not done so, but would invite testimonials.

Yet the TT retains some appeal. What exactly is it testing? What is the theory that fits this model? I think it might work as a double-blind exercise, where neither A nor B know that they are part of a test – similar to a teacher reading a student paper. But in that case, again, is B superfluous?

Header Photo: Image from Mohamed Hassan, Pixabay