Towards a Philosophy of Digitality: Gabriele Gramelsberger was awarded the K. Jon Barwise Prize

DAWID KASPROWICZ

On Thursday, January 9, 2025, KHK c:o/re director Gabriele Gramelsberger gave a lecture at the 121st annual meeting of the American Philosophical Association (APA), Eastern Division, in New York. Her lecture, titled “Philosophy of Digitality: The Origin of the Digital in Modern Philosophy”, was given in relation to the award of the K. Jon Barwise Prize by the APA in 2023 for her significant and sustained contributions to philosophy and computing.

photo credits: American Philosophical Association

Robin Hill, computer scientist from the University of Wyoming and a longtime member of the APA, introduced Prof. Gramelsberger and chaired through the session. Named after the American mathematician and philosopher K. Jon Barwise, the prize honors since 2002 scholars for their lifelong efforts in the disciplines of philosophy and computing, especially in the fields of artificial intelligence and computer ethics. Next to Prof. Gramelsberger, who received the prize for 2023, the Israelian philosopher Oron Shagrir from the Hebrew University Jerusalem received the Barwise Prize for 2024. Among the former winners of the prize are well-known philosophers such as Daniel Dennett, David Chalmers or Jack Copeland. Gabriele Gramelsberger was the third woman who won this award.

Prof. Gramelsberger presented two parts in her lecture: in the first, she introduced her conception of a philosophy of digitality since the modern age, and in the second, she highlighted some current challenges for philosophers to describe digitality as a socio-cultural phenomenon. It is not common in philosophy to relate the digital to thinkers of the modern age. In doing so, Prof. Gramelsberger began her talk with a schema how a prehistory of the digital could be written – a history that does not start with machines and technological objects, but with a reinterpretation of writings such as René Descartes’ Discourse de la méthode from 1637. In this classical book, Descartes did not only introduce a procedure how to separate right from wrong in scientific judging. Following Prof. Gramelsberger, he was also one of the first who systematically described thinking as a cognitive process, a process which could be distinguished in several steps that build up on each other. Instead of only considering the right inference from the premises (as done in syllogistic reasoning), Descartes also conceived thinking as a series of discrete steps that one has to execute appropriately to split a bigger problem into several smaller ones. It is this discrete and procedural way to describe thinking that we also find in the papers of the AI-pioneers Allan Newell and Herbert Simon and their General Problem Solver, as Prof. Gramelsberger argued.

While Descartes introduced the first discretization of cognitive processes, Leibniz went further to describe cognitive operations with a symbolic system. This artificial language consisting of arithmetic, algebra and logic should constitute the adequation between the object and the concept, between the relations of objects and the judgments. In this sense, Leibniz not only introduced the symbolic order to formulate possible experiences in the real world, he was also able to replace the qualitative and substance-oriented with a formal and quantitative one. This equivalence of being with the formal calculus allowed him to extend the conditions of possible experiences into the transcendence of mathematical operations. From here, Prof. Gramelsberger argued, it is not far anymore to rule-based cognitive operations that could also be externalized – and this is exactly what pioneers of digital computers such as C. Babbage did in the 19th century (see also in Gramelsberger 2023, p. 40-44).

The execution of such mechanized operations happens today a billion times in a couple of seconds. Taking into consideration, as Prof. Gramelsberger highlighted, that there are more than five billion smartphones in the world, a philosophy of digitality has also to respond to digital cultures and their objects as an everyday experience of most people. In this regard, Prof. Gramelsberger presented in the second half of her talk a more critical and phenomenological approach. It is the operation of digital machines beneath our “phenomenological thresfold” that represents on the one hand a challenge for a philosophy of digitality, but on the other hand also a risk for the wellbeing of the users. In referring to the German concept of “cultural techniques” (Kulturtechniken) (Krämer and Bredekamp 2013), Prof. Gramelsberger illustrated that in cultural techniques such as writing, one always operates with discretized symbols – whether in alphabets or in the arithmetic sense. The fundamental difference with digital machines lies in the affective mode by which they address us, as the Barwise-awardee explained. Most often, the goal of social media communication would be to raise emotions, but the resources to do so are affects that are triggered beneath our threshold of intentional attention. At the end of her talk, Prof. Gramelsberger pointed sharply out to a threatening constellation where man has lost its ability to be “eccentric”, as the German philosopher Helmuth Plessner called it. Instead, in the age of an affective smartphone culture and massive data-storage (often owned by private companies), man becomes centric again and stays in one place to go through a myriad of affective-loaded communications that keep him in a loop to create even more data.

In his response to Prof. Gramelsberger’s talk, Zed Adams from the New School for Social Research in New York extracted three leading questions: These questions highlighted the relation of the analog and the digital, the question of the copy in the age of the digital, and the challenge how to describe the affective regime in our current smartphone culture. Adams offers to dig deeper into the challenge of a “Philosophy of Digitality” were also taken up vividly by the audience. Especially the distinction of affect and emotion evoked some discussions, but also the challenge how to describe the cultural impact of technologies such as AI with philosophical tools. A first answer was to find ways how to describe the less complex yet emotionally overwhelming ways we can observe in the use of social media apps. This could be a fist step to better understand how machines in the age of AI recentralize us as human beings – or decentralize us as the contingent result of data-management.

Gabriele Gramelsberger. 2023. Philosophie des Digitalen. Zur Einführung. Junius: Hamburg.

Sybille Krämer and Horst Bredekamp. 2013. Culture, Technology, Cultural Techniques – Moving Beyond Text. In: Theory, Culture & Society 30(6): 20-29. DOI: 10.1177/0263276413496287

European Dialogue: Freedom of Research and the Future of Europe in Times of Uncertainty

JANA HAMBITZER

During a day-long symposium, part of the Freedom of Research: A European Summit – Science in Times of Uncertainty, speakers and panelists explored various aspects of freedom of research and the future of Europe in the context of ongoing global crises and conflicts.

“We should not think that freedom is self-evident. Freedom is at danger in every moment, and it is fragile”. With these cautioning words, Prof. Dr Thomas Prefi, Chairman of the Charlemagne Prize Foundation, welcomed the participants of the symposium on freedom of research, which took place at the forum M in the city center of Aachen on November 5, 2024.

As part of the Freedom of Research: A European Summit – Research in Times of Uncertainty, the Foundation of the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen, the Knowledge Hub and the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re) of RWTH Aachen University jointly provided an interdisciplinary platform to discuss the crucial role of freedom in scientific, social and political contexts concerning the future of Europe with researchers, policymakers, business representatives and the public.

The aim was to critically explore different forms and practices of implementing freedom of research in line with European principles and in support of democratic governance and societal benefits. The thematic focus of the symposium was on dealing with the numerous complex crises of our time – from military conflicts to right-wing populism – as well as addressing challenges associated with new technologies such as AI and the metaverse.

Humanity and Collaboration in the Age of Emerging Technologies

The strategic importance of freedom in fostering innovation and maintaining democratic values in a globally competitive landscape was emphasized by Wibke Reincke, Senior Director and Head of Public Policy at Novo Nordisk, and Dr Jakob Greiner, Vice President of European Affairs at Deutsche Telekom AG. From an industry perspective, both speakers underscored the need for open societies that invest in innovation to ensure the continuity and growth of democratic principles.

The emergence of the metaverse and other cutting-edge technologies were discussed by Jennifer Baker, Reporter and EU Tech Influencer 2019, Elena Bascone, Charlemagne Prize Fellow 2023/24, Nadina Iacob, Digital Economy Consultant at the World Bank, and Rebekka Weiß, LL.M., Head of Regulatory Policy, Senior Manager Government Affairs, Microsoft Germany. The panelists pointed out the essential role of human-centered approaches and international collaboration in addressing the ethical and societal challenges associated with new technologies, and in shaping the metaverse according to European ideals.

The inherent tension between technological progress and the preservation of research freedom was highlighted by Prof. Dr Gabriele Gramelsberger, Director of the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re), who raised the question of how AI is changing research. Prof. Dr Holger Hoos, Alexander von Humboldt Professor in AI and Executive Director of the AI Center at RWTH Aachen University, stated that publicly funded academic institutions must remain free from any influence of money and market pressure to foster cutting-edge research motivated solely by intellectual curiosity. Prof. Dr Benjamin Paaßen, Junior Professor for Knowledge Representation and Machine Learning at Bielefeld University, further argued that AI in research and education should only be used as a tool to complement human capabilities, rather than replace them.

Conflicts over Academic Freedom and the Role of Universities

The de facto implementation of academic freedom worldwide was presented by Dr Lars Lott from the research project Academic Freedom Index at the Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg. In a 50-year comparison, from 1973 to 2023, he illustrated a significant improvement of academic freedom in countries worldwide. However, looking from an individual perspective, the opposite is true: almost half of the world’s population lives in countries where academic freedom is severely restricted due to the rise of populist and authoritarian regimes.

Dr Dominik Brenner from the Central European University in Vienna reported firsthand on the forced relocation of the Central European University (CEU) from Budapest to Vienna and noted that such restrictions of academic freedom are an integral part of illiberal policies. Dr. Ece Cihan Ertem from the University of Vienna provided another example of increasing authoritarianism in academic institutions by discussing the suppression of academic freedom at Turkey’s Bogazici University by the government. Prof. Dr Carsten Reinhardt from Bielefeld University warned of the modern efforts in our societies to restrict academic freedom through fake news or alternative facts. From a historical perspective, these are fundamental attacks destroying the basis of truth finding,

referring to similar developments during the Nazi regime in Germany.

Another pressing issue, the precariousness of academic employment in Germany, was highlighted by Dr Kristin Eichhorn from the University of Stuttgart and co-founder of the #IchBinHanna initiative, protesting against academic labor reforms that disadvantage early and mid-career researchers. She pointed out that the majority of faculty work on fixed-term contracts, which significantly restricts researchers’ ability to exercise their fundamental right to academic freedom due to tendencies to suppress both structural and intellectual criticism.

How to deal with these challenges? Prof. Dr Stefan Böschen, Director of the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re), stressed that political assumptions and politically motivated conflicts can make academic discourse more difficult. However, it is important to foster dialogue once a common basis for discussion has been established. Frank Albrecht from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation advocated for greater efforts in science diplomacy and the vital role of academic institutions in international relations. Miranda Loli from the Robert Schuman Center for Advanced Studies, the European University Institute in Florence, and Charlemagne Prize Fellow 2023/24, emphasized the need for universities to act as reflexive communities that engage critically with the processes that shape academic freedom while recognizing their potential as informal diplomatic actors.

Research as a Basis for European Conflict Resolution

The intersection of academic freedom and conflict resolution was explored in a discussion between Dr Sven Koopmans, EU Special Representative for the Middle East Peace Process, and Drs René van der Linden, former President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and Dutch diplomat, moderated by Dr Mayssoun Zein Al Din, Managing Director of the North Rhine-Westphalian Academy for International Politics in Bonn. They argued that research is essential for understanding and resolving global conflicts and emphasized the role of the EU as a key player in international peace efforts. The two discussed the challenges of assessing conflicts from a European perspective, particularly the differing opinions of member states, and highlighted the EU’s economic power as a crucial factor in international peace efforts. Dr Koopmans emphasized the importance of an optimistic outlook, stating: “Let’s work on the basis – that there is a peace that we may one day achieve. It maybe sounds very difficult […], but you know: Defeat is not a strategy for success.”

The symposium underlined the critical importance of protecting freedom in research, science, and diplomacy. The discussions made clear that academic freedom is neither given nor a permanent state; rather, it requires continuous vigilance and proactive efforts to preserve. The collective message from the symposium reinforced that science in times of uncertainty can be navigated through regulation and governance for innovation, a strong European and international academic community, and independent universities as safe places to ensure the future of a democratic, secure and progressive Europe.

Photo Credits: Christian van’t Hoen

The Freedom We Stand For

RWTH KNOWLEDGE HUB

RWTH’s Freedom Late Night event brought a vibrant mix of guests to the Ludwig Forum, offering talks, discussions, performances, and entertainment that celebrated diverse perspectives on freedom.

“Why not cook a pot of soup and share it with your neighbors?” Publicist Marina Weisband’s suggestion at RWTH’s second Late Night event was one of the many unconventional ideas presented to bridge divides within society.

Held Monday evening at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, RWTH hosted a dynamic, entertaining, and insightful program on the theme of freedom. Moderated by journalist Claudia Kleinert and poetry slammer Luca Swieter, the event featured guests from culture, politics, sports, and academia, including Marina Weisband, actress Luise Befort, podcaster Dr. Ulf Buermeyer, former national soccer player Andreas Beck, and Borussia Mönchengladbach’s chief data analyst, Johannes Riegger.

Discussions across three stages explored freedom from sporting, cultural, scientific, philosophical, political, and social perspectives. Musical and artistic highlights included a specially choreographed performance by the dance ensemble Maureen Reeor & Company, the lively Popchorn pop choir, and the RWTH Big Band.

Throughout the evening, the unique setting of the Ludwig Forum underscored the importance of unity and the need to avoid societal divides. As Weisband noted, “With a bowl of soup in hand, engage with your neighbors to confront populist narratives together. Take the liberty to try something a bit daring now and then.”

The complexities of today’s reality were echoed by Dr. Domenica Dreyer-Plum from RWTH’s Institute of Political Science, who observed that while many people are frustrated with the current political and social climate and are tempted to protest or support extremist parties, “the AfD only seemingly has an answer to the big questions.”

For the academic guests, discussions naturally turned to freedom in research. Professor Verena Nitsch, head of RWTH’s Institute of Industrial Engineering and Ergonomics and chair of the University’s Ethics Commission, emphasized that the Commission’s role is not to restrict research, “but to train researchers to anticipate risks”.

“We live in times where technology is powerful, but wisdom is lacking,” added Professor Stefan Böschen, spokesperson for RWTH’s Human Technology Center and co-director of the “Cultures of Research” Käte Hamburger Center, highlighting the ethical challenges posed by AI and advanced technology.

Former judge and podcaster Dr. Ulf Buermeyer offered a practical take on restoring trust in politics: “We need substantial investment in railways and infrastructure like bridges. People need to see and feel that progress is happening. We can’t just talk our way out of this crisis.”

For actress Luise Befort (Club der roten Bänder, Der Palast), freedom is something many take for granted: “I am allowed to work in my profession – unlike so many women around the world.” Befort sees this as a profound privilege she does not take lightly.

Professional footballers, however, face a more limited kind of freedom. Johannes Riegger, chief data analyst at Bundesliga club Borussia Mönchengladbach, and former national player Andreas Beck (VfB Stuttgart, Besiktas Istanbul) shared anecdotes about the intense monitoring they undergo. Beck described how their movements on the field are tracked with advanced technology, making performance data highly transparent. Yet, according to Riegger, the level of surveillance is even greater in the United States, where athletes in major leagues are subjected to round-the-clock monitoring. By comparison, the monitoring in Germany is seen as manageable and part of the job.

A diverse lineup of speakers shared their insights on freedom and technology. Among them, Luise Befort; queer artist Lukas Moll, who warned that “technology can discriminate, and algorithms can reinforce stereotypes”; Frank Albrecht of the Humboldt Foundation, who reflected on “the privilege of living in a country like Germany, where academic freedom is highly valued”; screenwriter Jana Forkel, who said, “When it comes to creative work like screenwriting, AI poses no threat yet – this is where human input remains essential”; Volucap CEO Sven Bliedung von der Heide, who noted, “At Volucap, we’re pioneering new possibilities in film production, though our goal isn’t to replace actors entirely”; and author Betül Hisim, who observed, “AI can be a source of inspiration but is far from replacing the essence of what makes us human.”

The RWTH Late Night event was organized by the RWTH Knowledge Hub as part of the Freedom of Research Summit, a collaboration between the Stiftung Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen, the Knowledge Hub, and the Cultures of Research Käte Hamburger Center.

The RWTH Knowledge Hub is a vital instrument for transferring knowledge to society. “Knowledge isn’t only created at RWTH; it’s essential that we also share it with society – as we are doing tonight with the Late Night,” said Professor Matthias Wessling, Vice-Rector for Research Transfer at RWTH.

Despite their diverse perspectives, all the speakers agreed on one message: that freedom and democratic values require active effort. To quote Goethe: “This is the highest wisdom that I own; freedom and life are earned by those alone who conquer them each day anew.”

Photo Credits: Christian van’t Hoen

After Memory: Recalling and Foretelling across Time, Space, and Networks

NATHALIA LAVIGNE

AFTER MEMORY: An introduction about the long-term project co-developed by KHK c:o/re Junior Fellow Nathalia Lavigne, followed by a brief report about the symposium which took place last October in Karlsruhe, gathering specialists from arts, science and technology discussing the temporal, spatial, and social dimensions of digital memory in current times.

What comes after memory? I came across this question in one of the first drafts of the project AFTER MEMORY, developed together with the researchers Lisa Deml and Víctor Fancelli, while writing the opening remarks for the symposium AFTER MEMORY: Recalling and Foretelling across Time, Space, and Networks. The event took place in October (between 23rd and the 26th) at the ZKM | Center for Art and Media and at the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design (HfG), in Karlsruhe. During three and a half days, we had the chance to speculate about the temporal, spatial, and social dimensions of digital memory in an intense and vivid program – the first stage of this long-term project, which will continue in the following years with an exhibition and other formats.

Nathalia Lavigne

Nathalia Lavigne [she/her] works as an art researcher, writer and curator. Her research interests involve topics such as social documentation and circulation of images on social networks, cultural criticism, museum and media studies and art and technology.

This initial question still resonates, even if it’s hard to figure out any answer. Maybe it should be asked in a different way. It’s hard to imagine what is coming after memory since afterness is what has been lacking in recent times. Trapped, as we are, in an endless present, experiencing time perception obliterated by information overload, it is hard to find any sort of escape room that allows us to imagine what is about to come.

If modernism was marked by the ‘present future’ and many futuristic utopias, the end of the Cold War changed this perspective, when focus shifted to a ‘present past’ (Huyssen 2000). From autobiographies to the creation of different kinds of museums, from the emergence of new historiographical narratives to the reinvention of traditions, memory has become a trivial word, counted in the form of increasingly unlimited bytes. More recently, with the instantaneous mediation of reality and new archiving formats created by anyone, the goal of ‘total remembrance’, as Andreas Huyssen defined, has become unquestionable – although increasingly unattainable.

Different from other historical moments, we seem to be stuck in the present now. In a way, it shouldn’t be so bad: this is, after all, the only temporal condition that we can know. It’s in the present when memories are constantly updated; when we conceive in our imagination what is about to come. There are probably positive effects of changing the focus of the so-evoked future or past, as we did other times, and which have diverted our attention from what is happening now. But this is not what we can say based on our experience of being constantly “stuck on the platform”, to borrow the title of Geert Lovink’s recent book. If we have reached the end of “an era of possibilities and speculation”, as he affirms, what is the emergency exit for this reality in which platforms have closed any chance of collective imagination (p.42)?

If temporal fragmentation is far from a new thing, it is hard to deny that the internet complex (Crary, 2022) has made this feeling stronger. While our lives are displayed to us as thematic galleries assembled by automated digital systems whose rules we are unaware of, what happens in the present remains indecipherable and imperceptible. And especially under the circumstances imposed by the Covid-19, when the immersive experience of screens became the default perception, this effect was even stronger.

Needless to say that many of the ideas behind After Memory have their roots in what we lived during the pandemic, when most of us have experienced some episode of memory blur or digital amnesia. Although the impact of Covid-19 in our cognitive system is still unclear, recent studies reveal deficits in the performance of people a year or more after infection. Even the lockdown itself left marks, too, since spatial memory is essential in how we recollect events. And if time perception was especially obliterated during the pandemic, this feeling is inseparable from the well-known time-space compression, which was always related with capitalist expansion (Harvey 2012).But how different is this process nowadays, when the rise of generative AI, for instance, has created a new understanding about memory, making us confront a past that never really existed, as Andrew Hoskins has recently pointed out.

Photo Credits: Markus Breigt, KIT

Unmapping Landscapes, Endless Instants and Speculative (off-line) Networks

From some of these ideas, we developed the structure of After Memory’s symposium in three sections, each investigating an essential aspect of the conception and actualisation of memory: space (Unmapping Landscapes), time (Endless Instants), and communication (Speculative Networks). Dedicated to one of these specific programs, each day started with a workshop, which took place in a post-war modernist pavilion with glass walls and surrounded by a garden. Blankets on the floor invited participants to sit in a circle, or eventually to lie down as they saw fit. In some cases, the activities were interspersed with moments of meditation – either guided by sound or followed by a breathing technique such as Pranayama. In the end, we noticed how these morning sections played an important role in how the participants connected to each other, being more open to elaborate new ideas in a nonjudgmental atmosphere.

Photo Credits: Markus Breigt, KIT

When we were first offered this venue for hosting the workshops, the fact that there was no internet available was initially a concern. A wifi connection could be required in some activities, especially considering that networks and the digital sphere were some of the umbrella terms of the program. But we decided to keep the Pavilion in spite of that. On a more individual note, I am tempted to think that this was actually a reason which helped people to build connections that would continue beyond that moment. After this experience, I was more convinced to agree with the bold statement of Johnathan Crary in the opening of Scorched Earth – Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World: “If there is to be a liveable and shared future on our planet it will be a future offline, uncoupled from the world-destroying systems and operations of 24/7 capitalism” (2022, p.1).

In recent decades, social media has interwoven itself into the art system. Although the potential of the visual art field for creating connections has been present before the rise of these platforms, their constant use has made it nearly impossible for artists, cultural institutions, or the audience to avoid them, even as the controversies around how these platforms operate became more evident. In a moment when we have been talking about the end of a fantasy that Web 2.0 would be a democratic environment, especially due the problematic ties between platforms and authoritarian populism, it is crucial to imagine alternative ways of connecting which do not depend exclusively on them.

Photo Credits: Markus Breigt, KIT

During my fellowship at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research (c:o/re), I am interested in mapping how artists have been developing disruptive and speculative forms of networks from the mid-1990s to the present, but also, as a curator, in helping to implement projects that can contribute to generating new communications systems.

And if it is still not clear what comes after memory, or when, it seems important to experience these enquiries together, enabling memories to be updated more deeply through different understandings about time, space and, especially, communication.

Further reading and references:

Crary, Jonathan. 2022. Scorched earth: Beyond the digital age to a post-capitalist world. Verso Books: New York.

Harvey, David. 2012. “From space to place and back again: Reflections on the condition of postmodernity.” In: Mapping the futures, edited by John Bird, Barry Curtis, Tim Putnam and Lisa Tickner. Routledge: London, pp. 2-29.

Hoskins, Andrew. 2024. “AI and memory.” In: Memory, Mind & Media 3: e18.

Huyssen, Andreas. 2000. “En busca del tiempo futuro.” In: revista Puentes 1.2, pp. 12-29.

Lovink, Geert, et al. 2022. Extinction internet: our inconvenient truth moment. Institute of Network Cultures: Amsterdam.

Can nuclear history serve as a laboratory for the regulation of artificial intelligence?

ELISABETH RÖHRLICH

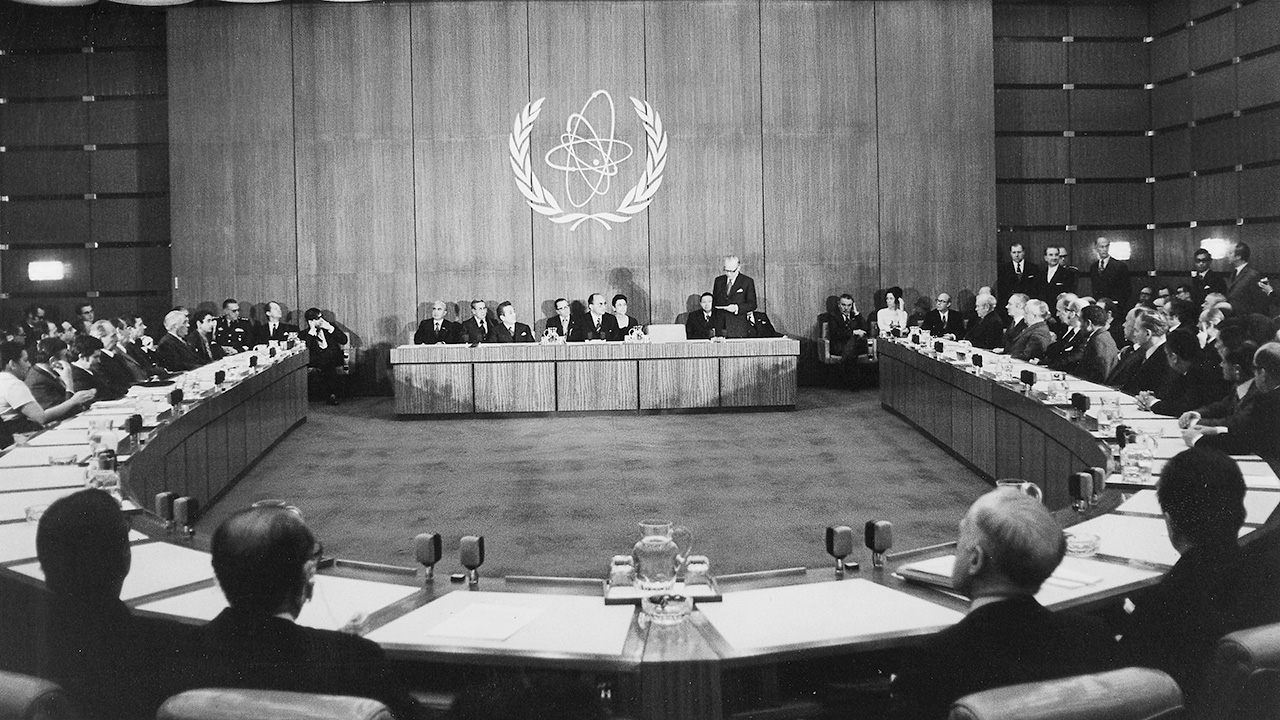

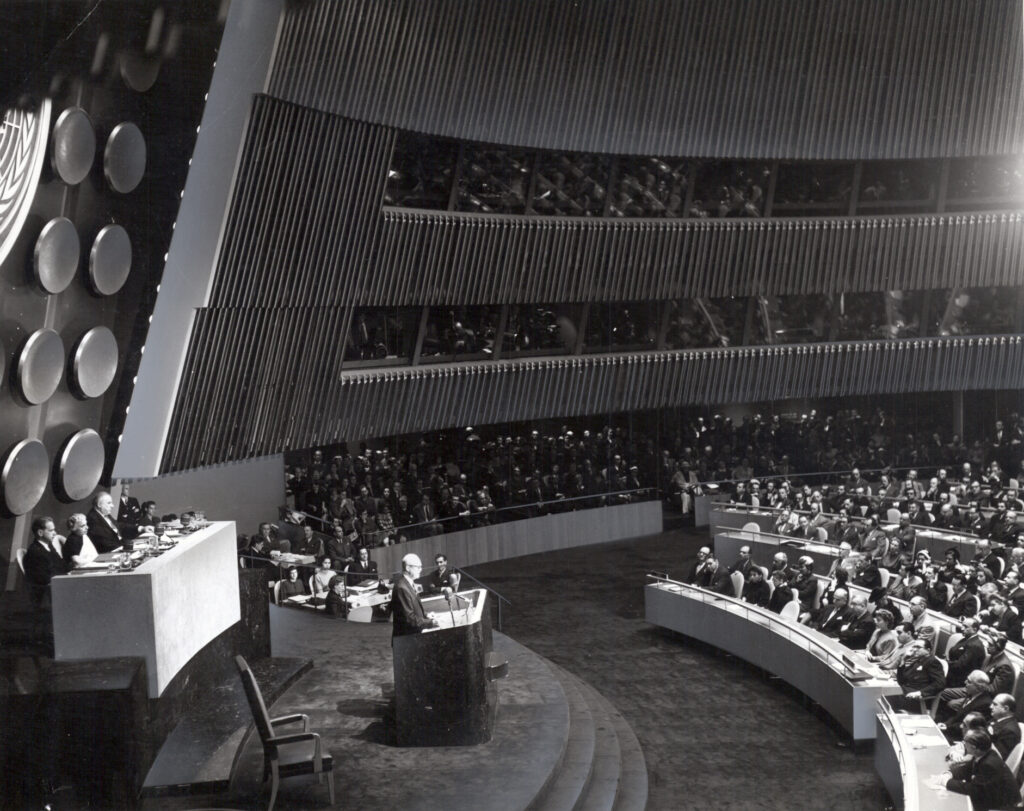

Artificial intelligence (AI) seems to be the epitome of the future. Yet the current debate about the global regulation of AI is full of references to the past. In his May 2023 testimony before the US Senate, Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI, named the successful creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a historical precedent for technology regulation. The IAEA was established in 1957, during a tense phase of the Cold War.

Calls for global AI governance have increased after the 2022 launch of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s text-generating AI chatbot. The rapid advancements in deep learning techniques evoke high expectations in the future uses of AI, but they also provoke concerns about the risks inherent in its uncontrolled growth. Next to very specific dangers—such as the misuse of large-language models for voter manipulation—a more general concern about AI as an existential threat—comparable to the advent of nuclear weapons and the Cold War nuclear arms race—is part of the debate.

Elisabeth Röhrlich

Elisabeth Röhrlich is an Associate Professor at the Department of History, University of Vienna, Austria. Her work focuses on the history of international organizations and global governance during the Cold War and after, particularly on the history of nuclear nonproliferation and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

From nukes to neural networks

As a historian of international relations and global governance, the dynamics of the current debate about AI regulation caught my attention. As a historian of the nuclear age, I was curious. Are we witnessing AI’s “Oppenheimer moment,” as some have suggested? Policymakers, experts, and journalists who compare the current state of AI with that of nuclear technology in the 1940s suggest that AI has a similar dual use potential for beneficial and harmful applications—and that we are at a similarly critical moment in history.

Some prominent voices have emphasized analogies between the threats posed by artificial intelligence and nuclear technologies. Hundreds of AI and policy experts signed a Statement on AI Risk that put the control of artificial intelligence on a level with the prevention of nuclear war. Sociologists, philosophers, political scientists, STS scholars, and other experts are grappling with the question of how to develop global instruments for the regulation of AI and have used nuclear and other analogies to inform the debate.

(Credits)

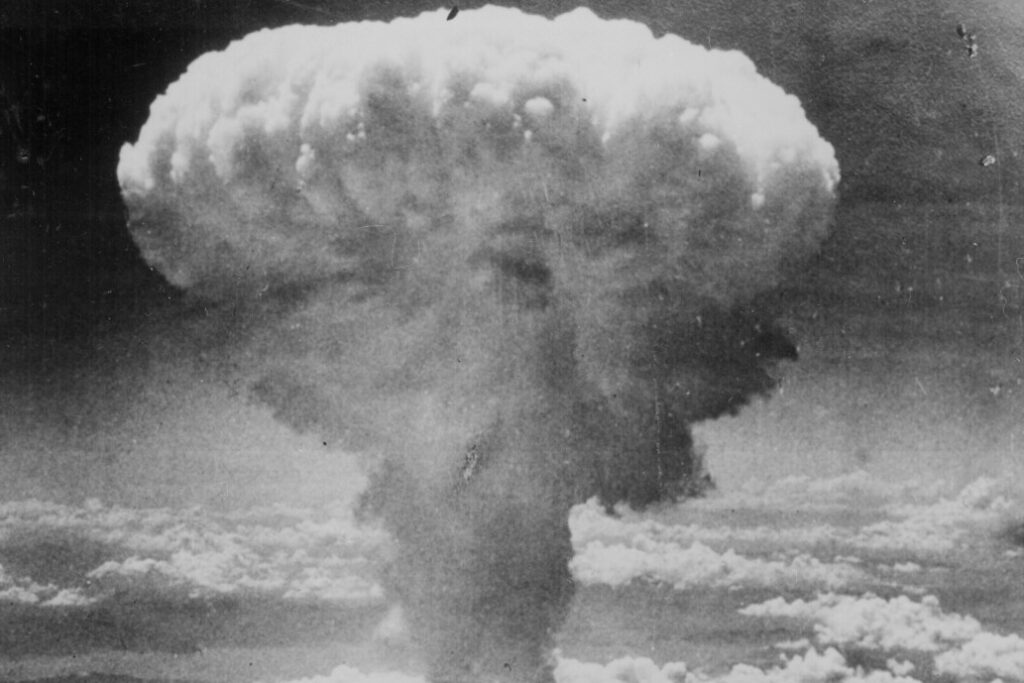

There are popular counterarguments to the analogy. When the foundations of today’s global nuclear order were laid in the mid-1950s, risky nuclear technologies were largely in states’ hands, while today’s development of AI is driven much more by industry. Others have argued that there is “no hard scientific evidence of an existential and catastrophic risk posed by AI” that is comparable to the threat of nuclear weapons. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 had drastically demonstrated the horrors of nuclear war. There is no similar testimony for the potential existential threats of AI. However, the narrative that because of the shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki world leaders were convinced that they needed to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons is too simple.

Don’t expect too much from simple analogies

At a time of competing visions for the global regulation of artificial intelligence—the world’s first AI act, the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, just entered into force in August 2024—a broad and interdisciplinary dialog on the issue seems to be critical. In this interdisciplinary dialog, history can help us understand the complex dynamics of global governance and scrutinize simple analogies. Historical analysis can place the current quest for AI governance in the long history of international technology regulation that goes back to the 19th century. In 1865, the International Telegraph Union was founded in Paris: the new technology demanded cross-border agreements. Since then, any major technology innovation spurred calls for new international laws and organizations—from civil aviation to outer space, from stem cell technologies to the internet.

For the founders of the global nuclear order, the prospect of nuclear energy looked just as uncertain as the future of AI appears to policymakers today. Several protagonists of the early nuclear age believed that they could not prevent the global spread of nuclear weapons anyway. After the end of World War II, it took over a decade to build the first international nuclear authority.

In my recent book Inspectors for Peace: A History of the International Atomic Energy Agency, I followed the IAEA’s evolution from its creation to its more recent past. As the history of the IAEA’s creation shows, building technology regulation is never just about managing risks, it is also about claiming leadership in a certain field. In the early nuclear age—just as today with AI—national, regional, and international actors competed in laying out the rules for nuclear governance. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented his 1953 proposal to create the IAEA—the famous “Atoms for Peace” initiative—as an effort to share civilian nuclear technology and preventing the global spread of nuclear weapons. But at the same time, it was an attempt to legitimize the development of nuclear technologies despite its risks, to divert public attention from the military to the peaceful atom, and to shape the new emerging world order.

Simple historical analogies tend to underestimate the complexity of global governance. Take for instance the argument that there are hard lines between the peaceful and the dangerous uses of nuclear technology, while such clear lines are missing for AI. Historically, most nuclear proliferation crises centered around opposing views of where the line is. The thresholds between harmful and beneficial uses do not simply come with a certain technology, they are the result of complex political, legal, and technical negotiations and learnings. The development of the nuclear nonproliferation regime shows that not the most fool-proof instruments were implemented, but those that states (or other involved actors) were willing to agree on.

History offers lessons, but does not provide blueprints

Nuclear history offers more differentiated lessons about global governance than the focus on the pros and cons of the nuclear-AI analogy suggests. Historical analysis can help us understand the complex conditions of building global governance in times of uncertainty. It reminds us that the global order and its instruments are in continuous process and that technology governance competes with (or supports) other policy goals. If we compare nuclear energy and artificial intelligence to inform the debate about AI governance, we should avoid ahistorical juxtapositions.

The Leibniz Puzzle

GABRIELE GRAMELSBERGER

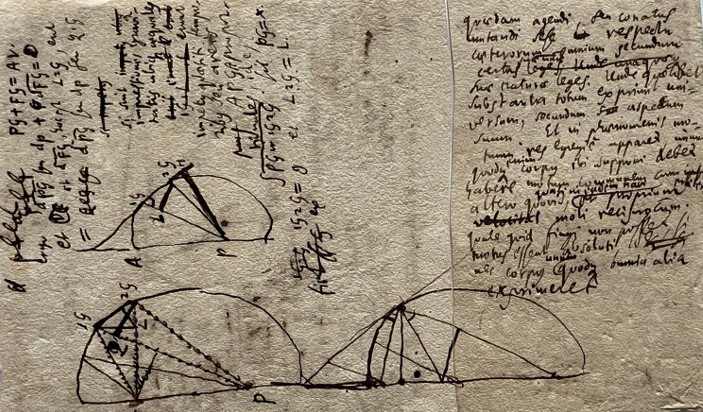

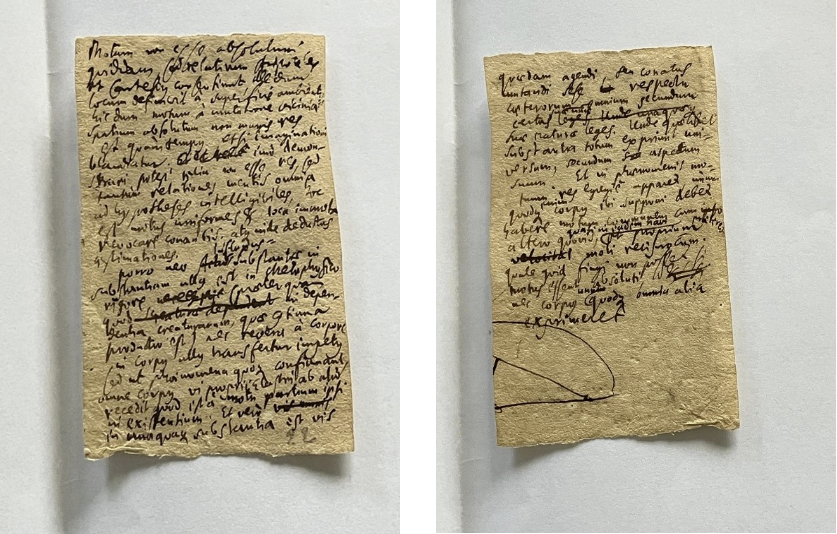

On the occasion of an invitation to a lecture on Leibniz as a forerunner of today’s artificial intelligence at the Leibniz Library in Hannover, where most of his manuscripts are kept and edited, I had the opportunity to see some excerpts from his vast oeuvre. Prof. Michael Kempe, head of the research department of the Leibniz Edition, gave me some insights into the practice of editing Leibniz’s writings. Leibniz literally wrote on every piece of paper he could get his hands on. Hundreds of thousands of notes, because Leibniz wrote various notes on a large sheet of handmade paper and then cut it up himself to sort the individual notes thematically. A kind of early note box. However, he did not actually sort many of his notes and left behind a jumble of snippets.

How do you deal with the jumble of 100,000 snippets?

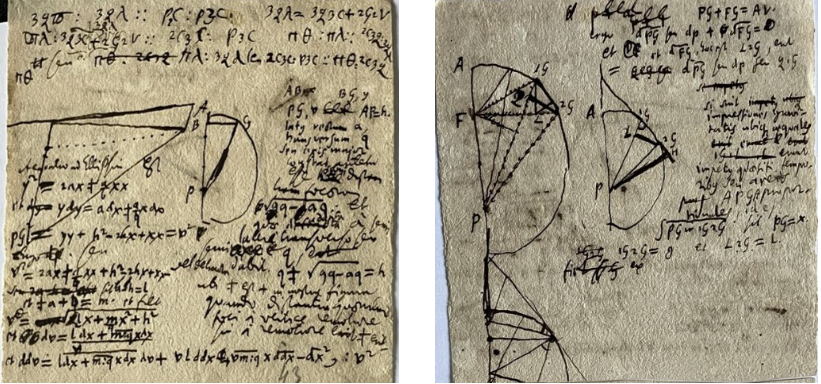

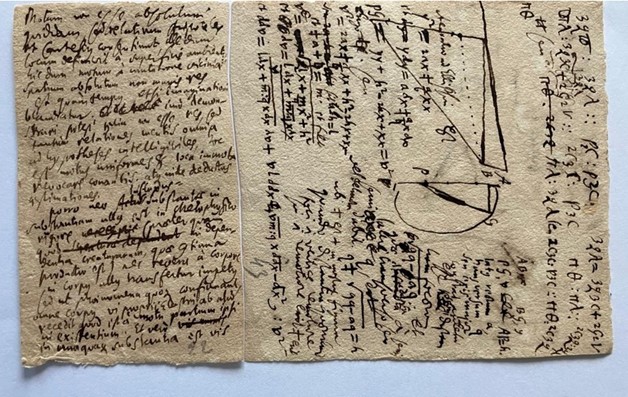

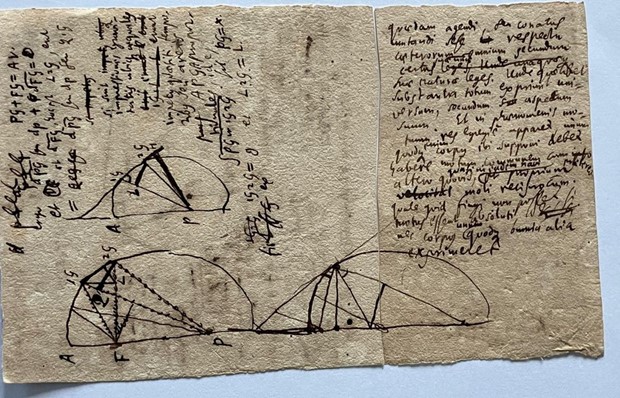

Nowadays, Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology is used to put together the “puzzle”, as Michael Kemper calls it. Supported by MusterFabrik Berlin, which specializes in such material cultural heritage puzzles, the snippets are reassembled again and again and reveal many surprises. For example, a snippet of Leibniz’s idea on “Motum non esse absolutum quiddam, sed relativum …” (Fig. 2 front/back side) showed a fragment of a geometric drawing. However, the snippet 22 preserved in box LH35, 12, 2 was not completed by any other snippet in this box. The notes were sorted by hand in the late 19th century by the historian Paul Ritter (Ritter catalog) as a basis for a later edition. Ritter’s catalog was a first attempt to bring some order to the scattered notes. Now, more than a hundred years later, AI technology is bringing new connections and affiliations to light. Snippet 43, shown in Figure 3 (front/back side), completed this part of the puzzle. It was located in box LH35, 10, 7 and had never before been connected to snippet 22.

Trains of thought made visible

“What these recombined snippets tell us,” says Michael Kempe, “is how Leibniz’s thinking worked. He used writing to organize and clarify his thoughts. He wrote all the time, from morning, just after waking up, until late at night. And he often used drawings to illustrate, but also to test his ideas. He changed the sketches and thus further developed his train of thought.” Combined snippets 22/43 are such an example. While writing about the relativity of motion, Leibniz made some geometric sketches of the motion of the planets and added some calculations (fig. 4b).

Leibniz’ contributions to AI

An interesting side aspect is that the AI technology, used for solving the Leibniz puzzle, is based on a modern version of Leonhard Euler’s polyhedron equation, which was inspired by Leibniz’s De Analysi situs. De Analysi situs, in turn, was the topic of my talk the day before on the influence of Leibniz’s ideas on AI technology. So, it all fitted together very well. However, Leibniz’ contributions to AI were manifold. Already his contribution to computation were outstanding—he had developed a dyadic calculation system, an arithmetic mechanism (Leibniz wheel), which was in use until the beginning of the 20th century, and directed the construction of a four species arithmetic machine. However, his contribution to a calculus of logic was even more significant, because he had to overcome sensory intuition and to develop an abstract intuition solely based on symbolic data. De Analysi situs was precisely about this abstract stance, which came into use only in 19th century’s symbolic logic. Furthermore, De Analysi situs is considered a precursor of topology, which inspired Euler’s polyhedron equation, which expresses topological forms with graphs. Graphs, in turn, play a crucial role in AI for network analysis of all types of data points and relationships. This closes the circle from Leibniz to AI.

De Analysi situs (1693)

How did Leibniz overcome sensory intuition and develop an abstract intuition solely based on data points and relationships? The text begins with the following sentences: “The commonly known mathematical analysis is one of quantities, not of position, and is thus directly and immediately related to arithmetic, but can only be applied to geometry in a roundabout way. Hence it is that from the consideration of position much results with ease which can be shown by algebraic calculation only in a laborious manner” (Leibniz, 1693, p. 69). Leibniz criticized the limited arithmetic operativity of algebraic analysis (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, square root) and called for the expansion of operations through the analytical method for geometry and geometrical positions.

This expansion was the following: “The figure generally contains, in addition to quantity, a certain quality or form, and just as that which has the same quantity is equal, so that which has the same form is similar. The theory of similarity or of forms extends further than mathematics and is derived from metaphysics, although it is also used in mathematics in many ways and is even useful in algebraic calculus. Above all, however, similarity comes into consideration in the relations of position or the figures of geometry. A truly geometrical analysis must therefore apply not only equality and proportion […] but also similarity and congruence, which arise from the combination of equality and similarity” (p. 71).

Leibniz criticized that it was the fault of the philosophers, who were content with vague definitions. And now comes the decisive step: he proposed an exact definition for the concept of similarity. He writes: “I have now, by an explanation of the quality or form which I have established, arrived at the determination that similar is that which cannot be distinguished from one another when observed by itself” (pp. 71-72). Thus, he replaced similarity by indistinguishability and argued that indistinguishability only requires the comparison of data “salva veritate.” He thus established a concept of indistinguishability which can “be derived from the symbols by means of a secure computations and proof procedure” (p. 76), which is the basis of all data operations to this day.

With this algorithm, Leibniz hoped, that “all the questions for which the faculty of perception is no longer sufficient can be pursued further, so that the calculus of position described here represents the complement of sensory perception and, as it were, its completion. Furthermore, in addition to geometry, it will also permit hitherto unknown applications in the invention of machines and in the description of the mechanisms of nature” (p. 76). It is an algorithm that is intended to help recognize similarities purely on the basis of data. Today, we call this clustering and it is the central strategy of unsupervised learning, i.e. a method for discovering similarity structures in large data sets.

References and further readings

De Risi, Vincenzo: The Analysis Situs 1712-1716, Geometry and Philosophy of Space in the Late Leibniz, Basel: Birkhäuser 2006.

Gramelsberger, Gabriele: Operative Epistemologie. (Re-)Organisation von Anschauung und Erfahrung durch die Formkraft der Mathematik, Hamburg: Meiner 2020. Open access URL: https://meiner.de/operative-epistemologie-15229.html

Gramelsberger, Gabriele: Philosophie des Digitalen zur Einführung, Hamburg: Junius 2023.

Kempe, Michael: Die beste aller möglichen Welten: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in seiner Zeit, S. Fischer: München 2022.

Leibniz, Gottfried W.: De analysi situs (1693), in: Philosophische Werke (ed. by Artur Buchenau and Ernst Cassirer), vol. 1, Meiner: Hamburg 1996, pp. 69–76. (All quotes translated by DeepL).

Ziegler, Günter M., Blatter, Christian: Euler’s polyhedron formula — a starting point of today’s polytope theory, Write-up of a lecture given by GMZ at the International Euler Symposium in Basel, May 31/June 1, 2007. URL: https://www.mi.fu-berlin.de/math/groups/discgeom/ziegler/Preprintfiles/108PREPRINT.pdf

Towards Expanding STS?

MARCUS CARRIER

On October 9, 2024, KHK c:o/re director Prof. Dr. Stefan Böschen opened the new lecture series “Expanding Science and Technology Studies”. His talk titled “Towards Expanding STS?” was aimed at setting the scene for the lecture series and served as a starting point for further reflections on the topic. The talk was mostly designed around sketching out the problems that, as Prof. Böschen argues, classical Science and Technology Studies (STS) are not equipped to tackle alone. Instead, he argues for an expansion of STS towards other disciplines that investigate Science and Technology, namely History of Science and Philosophy of Science, to better grasp these problems.

Prof. Böschen started his talk with presenting his own personal starting points for thinking about this topic. First, there is the new concept of “Synthetica” or new forms of life that are designed by humans which also played a role in the opening talk by KHK c:o/re director Prof. Gramelsberger for the 2023/2024 lecture series “Lifelikeness”. Prof. Böschen now asked whether these Synthetica are epistemic objects or technical objects and if STS are equipped to describe the practice around them. Second, he talked about sustainable development goals. These are very knowledge intensive, but at the same time the knowledge management has to be done by different countries which also have to take into account different forms of knowledge and have to manage a lot of diversity in the system. Third, Prof. Böschen reflected on different formats he experienced that made him think further on expanding STS: The Temporary University Hambach that was designed around the structural change in the Rhinish Revier and based on the needs of local people, and the STS Hub 2023 in Aachen which was designed to bring together different disciplines doing “science on science.”

After having set the scene with these personal starting points, Prof. Böschen claimed that there are signs for science changing significantly. First, he concentrated on the cluster of topics around digitization and especially the digitization of problem-solving in science. This cluster includes topics like digital models both for scenario building and for reducing the space of options where real-world problems must be transformed to be computable by which models shape the way of thinking in science. But also, the digitization of scientific literature to grasp the ever-growing amount as well as the digitization of experiments which can pose challenges for expectations of reproducibility are part of this cluster.

In the tension of simplification for the sake of problem-solving and complexifying to better understand specific contexts, Prof. Böschen argued that digital tools are steered towards simplification. This, in turn, creates new and specific concerns about the epistemic quality of knowledge produced by these tools and about the way they transform research in practice.

The second cluster of topics that Prof. Böschen argued are a sign of significant change in science is the de-centralization of knowledge production exemplified in projects like living labs which were also part of recent talk by Dr. Darren Sharp at the KHK c:o/re. Programs like living labs, where science encourages society to participate in the making of solutions for local issues, can have two forms. On the one hand side, they can in collaborative ways explore the status quo and define what should be understood as the “problem” before bringing together local experiences and knowledge as well as scientific knowledge to solve it. On the other hand, living labs can start out with a technological innovation and can then locally look for applications and use-cases for this innovation. The technology can then be optimized towards local needs.

In both forms of living labs, the important new criterion for knowledge is relevance which entails the question for whom it should be relevant and who defines that. Also, these local solutions and optimizations face problems of scaling. How can they be scaled up and are the “problems” on all scaling level still the same? Lastly, how does it impact knowledge production on a deeper level?

Both, the digitization of science and the de-centralization of knowledge production show that science is in the midst of a transformation according to Prof. Böschen. There is a need for a relational analysis of epistemic quality and epistemic authority. He shares his intuition to preserve the ideal of reliable scientific knowledge and that knowledge production for decision making processes has an epistemic as well as an institutional side. This, Prof. Böschen argues, can not be done by any discipline alone but needs collaboration between the sociologically and ethnographically centered STS and more philosophically and historically oriented research on science. Expanded STS as Prof. Böschen envisions it should tailor new concepts for analyzing research during transformation.

With this call to action, Prof. Böschen leaves not with a set program but with a description of problems that call for future interdisciplinary discussions.

On October 30, 2024, the next talk of the Lecture Series titled “An IAEA for AI? The Regulation of Artificial Intelligence and Governance Models from the Nuclear Age” will be by our fellow Elisabeth Röhrlich. We look forward to continuing the conversation!

Workshop “Epistemology of Arithmetic: New Philosophy for New Times”

The Käte Hamburger Kolleg on Cultures of Research hosted a philosophical Workshop on May 16th and 17th May. It was organized by Markus Pantsar and Gabriele Gramelsberger for good reasons: Gabriele Gramelsberger received as the first German philosopher the K. Jon Barwise Prize, while Markus Pantsar’s book “From Numerical Cognition to the Epistemology of Arithmetic” had been recently published by Cambridge University Press as the first book publication by a fellow at the KHK Aachen.

Markus Pantsar: “From Numerical Cognition to the Epistemology of Arithmetic”

The workshop kicked off with a presentation by Markus Pantsar (RWTH Aachen University) on how his book came to be. The leading question is: how can we use empirical knowledge about numerical cognition to gain a better understanding of arithmetical knowledge? His goal is to combine philosophy of mathematics with the cognitive sciences to gain a deeper understanding of how we develop and acquire number concepts and their arithmetic. It’s fascinating how these concepts develop differently across cultures, even though they are based on universal proto-arithmetical numerical abilities. Indeed, even animals have proto-arithmetical abilities, evidenced by their ability to differentiate on collections based on numerosities. This leads to an intriguing question: how do we come to develop and acquire number concepts? From an anthropological perspective, numbers are a fundamental aspect of human life in many cultures, yet there are also cultures without numbers. Hence, aside from the evolutionarily developed proto-arithmetical abilities, we also need to focus on the cultural foundations of arithmetic. All this, Pantsar argued, is relevant for the epistemology of arithmetic.

Dirk Schlimm: “Where do mathematical symbols come from?”

Dirk Schlimm from McGill University in Montreal was the next to present. He talked about his recent research project on mathematical notations. Grounding on the question of what notations are (according to Peirce), Schlimm introduced his newest findings that mathematical notations are sometimes arbitrary, but this is not the case generally. Mathematical symbols may resemble or draw from shapes in the real world, or have other characteristics that connect to our cognitive capacities. The issue is, however, very complex. Mathematical symbols, in particular, carry many purposes and their use needs to be studied with this in mind. In addition to purely scientific purposes, we should consider how academic practices and political dimensions influence the acceptance and use of notations.

Richard Menary: “The multiple routes of enculturation”

Richard Menary (Macquarie University, Sydney) then gave us insights into his research on enculturation, arguing that there are multiple cultural pathways to developing and acquiring number concepts and arithmetic. Menary calls this the multiple routes model of enculturation. He discussed aspects of Pantsar’s book, especially the developmental path from proto-arithmetical cognition to arithmetical cognition. Menary showed a variety of factors in how this transition can take place, like finger counting, writing and forming numbers on paper. Enculturation through cultural practices has a significant influence on the development of arithmetical abilities, but we should not be fooled into thinking that such enculturation is a uniform phenomenon that always follows similar paths.

Regina Fabry: “Enculturation gone bad: The Case of math anxiety”

Regina Fabry (Macquarie University) showed in her presentation on math anxiety how the relationship between cognition and affectivity needs to be included in accounts of arithmetical knowledge. While accounts of enculturation, like those of Menary and Pantsar, focus on the successful side of things, it is important to acknowledge that processes of enculturation can also go bad. Socio-cultural factors associated with mathematics education can lead to anxiety, which hinders the learning process with long-standing consequences. Empirical studies can contribute to a better understanding of where epistemic injustice may be present, and where there is a strong link to math anxiety. Accounts of arithmetical knowledge drawing from enculturation should be sensitive to such problems, but we can also use research on math anxiety to understand better the role of affectivity in enculturation in general.

Catarina Dutilh Novaes: “Dialogical pragmatism and the justification of deduction”

On Friday, Catarina Dutilh Novaes from Vrije University of Amsterdam discussed her ongoing investigation on the dialogical roots of deduction and posed the question what, if anything, can justify deductive reasoning. While her book The Dialogical Roots of Deduction offers an analysis of deduction as it is present in cultural practices, the question of its justification is left open. In her talk, she discussed whether pragmatist approaches could fill the gap to ground deduction. She argued that the justification for deduction comes from nothing beyond the pragmatics of the dialogical development of deduction. She supported this claim by a discussion on pragmatist theories of truth and recent discussion on anti-exceptionalism in logic.

Frederik Stjernfelt: “Peirce’s Philosophy of Notations and the Trade-offs in Comparing Numeral Symbol Systems”

The former KHK Fellow Frederik Stjernfelt (Aalborg University Copenhagen) talked about his recent studies on Charles S. Peirce’s work on notations, co-conducted with Pantsar. Although better known for his work on logical notation, Peirce was deeply interested also in mathematical notation, including numeral symbol systems. He was eager to find a fitting notation for numbers which is easy to learn and allows easy calculations. Peirce focused in particular on the binary and heximal systems, the latter of which he considered superior to our decimal system. Stjernfelt presented Peirce-inspired criteria for different aims of numeral symbol systems, like iconicity, simplicity, and ease of calculation, arguing that the choice of a symbol system comes with trade-offs between them.

Stefan Buijsman: “Getting to numerical content from proto-arithmetic”

Stefan Buijsman (TU Delft) discussed Pantsar’s account of how humans arrive from proto-arithmetical abilities to proper arithmetical abilities. Studies of young children suggest that the core cognitive object-tracking system (OTS) and approximate number system (ANS) can both play a role in this process, but a key stage is acquiring the successor principle (that for every number n, also n + 1 is a number). Buijsman emphasized the role of acquiring the number concept one and its importance in grasping the successor principle, noting that Pantsar’s account could benefit from more focus on the special character of acquiring the first number concept.

Alexandre Hocquet: “Reproducibility, Photoshop, Pubpeer, and Collective Disciplining”

With Alexandre Hocquet’s (Université de Lorraine/ Laboratory Archives Henri-Poincaré) talk, the workshop moved from the philosophy of arithmetic to digital and computational approaches to philosophy of science. Hocquet discussed Photoshopping scientific digital images and using them for fraud in academic research, focusing on the Voinnet affair. On this basis, he discussed the topics of trust, reproducibility and change of scientific methods. With the use of digital images as evidence, new considerations of transparency are needed to ensure trust in scientific practice.

Gabriele Gramelsberger and Andreas Kaminski: “From Calculation to Computation. Philosophy of Computational Sciences in the Making”

In the final talk of the workshop, Gabriele Gramelsberger (RWTH Aachen University) and Andreas Kaminski (TU Darmstadt) focused on the computational turn in science. While mathematics has been an indispensable part of science for centuries, the increasing use of computer simulations has replaced arithmetical calculations by Boolean computations. Gramelsberger discussed the cognitive limitations of interpreting non-linear computing systems. Kaminski then considered questions of epistemic, pragmatic, and ethical opacity that arise from these limitations.

From bio-ontologies to academic lives: What studying biocuration can tell us about the conditions of academic work

SARAH R. DAVIES

When I arrived at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg in February 2024, my plan was to study bio-ontologies: the systems that are used to categorise and organise biological data. As a Science and Technology Studies (STS) researcher, I had been interested in biocuration for a while, and one key aspect of biocuration work is developing and applying ontologies. Exploring bio-ontologies would, I thought, give me important insights into the practice of biocuration and what it is doing to our understandings of biology, the organisms, and entities that are studied, and ideas about ‘life’ itself.

Sarah R. Davies

Sarah R. Davies is Professor of Technosciences, Materiality, and Digital Cultures at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, University of Vienna, Austria.

Her work explores the intersections between science, technology, and society, with a particular focus on digital tools and spaces.

I am a social scientist, so delving into the nature of bio-ontologies by looking at natural science and philosophy literature about them was something of a departure for me. What I hadn’t necessarily expected was that doing so would bring me back to more sociological questions, in particular regarding the conditions of academic work. In other words, studying bio-ontologies led me to argue that these systems, which are “axioms that form a model of a portion of (a conceptualization) of reality”[1]Bodenreider, Olivier, and Robert Stevens. 2006. “Bio-ontologies: current trends and future directions.” Briefings in Bioinformatics 7 (3): 256–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbl027., are connected not just to forms of life in the context of biological entities, but with regard to the researchers who create and use them.

Let me rewind a bit. What is biocuration, and what exactly are bio-ontologies? Biocuration is “the process of identifying, organising, correcting, annotating, standardising, and enriching biological data”. [2]Tang, Y. Amy, Klemens Pichler, Anja Füllgrabe, Jane Lomax, James Malone, Monica C. Munoz-Torres, Drashtti V. Vasant, Eleanor Williams, and Melissa Haendel. 2019. “Ten quick tips for … Continue reading Its “primary role … is to extract knowledge from biological data and convert it into a structured, computable form via manual, semi-automated and automated methods.”[3]Quaglia, Federica, Rama Balakrishnan, Susan M Bello, and Nicole Vasilevsky. 2022. “Conference report: Biocuration 2021 Virtual Conference.” Database 2022 (Januar): baac027. … Continue reading This is largely done in the context of large data- and knowledgebases (such as FlyBase or UniProt), which are now central to the biosciences. Biocurators work to develop and maintain such databases, for example by reading scientific articles and extracting useful information from them, inputting data into databases, adding metadata and annotating information, and – importantly – creating and using the bio-ontologies I have already mentioned.

Bio-ontologies, then, are a means of classifying and organising biological data. They offer a ‘controlled vocabulary’ (meaning a standardised terminology), but also represent current knowledge about biological entities in that they consist of “a network of related terms, where each term denotes a specific biological phenomenon and is used as a category to classify data relevant to the study of that phenomenon.”[4]Leonelli, Sabina. 2012. “Classificatory Theory in Data-intensive Science: The Case of Open Biomedical Ontologies.” International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 26 (1): 47–65. … Continue reading Bio-ontologies such as the Gene Ontology therefore offer not only a means of accessing knowledge and data, but investigating biological phenomena by creating, as noted on the Gene Ontology’s website, “a foundation for computational analysis of large-scale molecular biology and genetics experiments in biomedical research”.

As I looked into the nature of bio-ontologies, it became clear to me that these organisational systems for biodata are hugely important. They allow researchers in the biosciences to access current knowledge and relevant data (not always easy in the midst of a ‘data deluge’), but they also have epistemic significance. As Sabina Leonelli writes, bio-ontologies “constitute a form of scientific theorizing that has the potential to affect the direction and practice of experimental biology.”[5]Ibid. The development and application of ontologies to biological data thus renders the contemporary biosciences thinkable, capturing the current state of the art and allowing researchers to extrapolate from that.

Given this significance, it is perhaps somewhat surprising that biocuration, as an area of science, often goes unnoticed by its users and by research funders. As one biocurator told me:

…we are in the background. Even researchers who heavily use these resources [databases], don’t usually know our names and don’t think about us existing. But they love the resource. And that’s actually something we’ve gotten with the booth when we were at conferences. People will come up and be like, oh you are the [resource]! Wow, you are good, awesome. They are kind of shocked that there’s humans there.[6]Davies, Sarah R., and Constantin Holmer. 2024. “Care, collaboration, and service in academic data work: biocuration as ‘academia otherwise.'” Information, Communication & … Continue reading

Biocurators are not only ‘in the background’, they frequently struggle to get sustained funding for their work, and generally need to build careers through a series of temporary contracts. Perhaps because databases are machine-readable and can be queried automatically, both funders and the researchers who use curated resources often seem to imagine that the work of biocuration can be readily carried out through automated means; in practice, while biocurators make use of automated tools such as text-mining, interpreting scientific literature and annotating data is a highly skilled activity that cannot be easily replicated by AI or other technologies.

Why is biocuration so under-valued despite its epistemic importance? One answer is that biocuration does not fit well with current systems of reward and evaluation within academia. Researchers are, for instance, rewarded for publishing frequently and in high-profile journals, but biocurators produce other kinds of outputs to journal articles – the data – and knowledgebases that they work on. Similarly, gaining research funding is typically seen as a sign of a successful academic, but biocurators’ work does not fit well into the categories that funders use to assess research quality (such as novelty). As Ankeny and Leonelli explain:

Value in science (be it of individual researchers or particular research projects) is largely calculated on the basis of the number of publications produced, the quality of the journals in which those publications appeared, and the impact of the publications as measured by citation indices and other measures: given that [data] donation and curation are still largely unrecognized, the value of these activities correspondingly is limited in part because it cannot be measured using traditional metrics.[7]Ankeny, Rachel A., and Sabina Leonelli. 2015. “Valuing Data in Postgenomic Biology:: How Data Donation and Curation Practices Challenge the Scientific Publication System.” In … Continue reading

Studying bio-ontologies thus led me to consider the lives of their creators, and the conditions under which they work. Despite the epistemic significance of biocuration, it escapes recognition under contemporary ways of crediting and rewarding academic work – something which seems to me to be deeply unfair. Perhaps, then, we need to find new ways of valuing, funding, and rewarding the wide variety of epistemic contributions made within research, rather than relying on metrics such as number of publications and citations as the key means of assessing research?

References

| ↑1 | Bodenreider, Olivier, and Robert Stevens. 2006. “Bio-ontologies: current trends and future directions.” Briefings in Bioinformatics 7 (3): 256–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbl027. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Tang, Y. Amy, Klemens Pichler, Anja Füllgrabe, Jane Lomax, James Malone, Monica C. Munoz-Torres, Drashtti V. Vasant, Eleanor Williams, and Melissa Haendel. 2019. “Ten quick tips for biocuration.” PLoS Computational Biology 15 (5): e1006906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006906 |

| ↑3 | Quaglia, Federica, Rama Balakrishnan, Susan M Bello, and Nicole Vasilevsky. 2022. “Conference report: Biocuration 2021 Virtual Conference.” Database 2022 (Januar): baac027. https://doi.org/10.1093/database/baac027 |

| ↑4 | Leonelli, Sabina. 2012. “Classificatory Theory in Data-intensive Science: The Case of Open Biomedical Ontologies.” International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 26 (1): 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/02698595.2012.653119. |

| ↑5 | Ibid. |

| ↑6 | Davies, Sarah R., and Constantin Holmer. 2024. “Care, collaboration, and service in academic data work: biocuration as ‘academia otherwise.'” Information, Communication & Society 27 (4): 683–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2024.2315285. |

| ↑7 | Ankeny, Rachel A., and Sabina Leonelli. 2015. “Valuing Data in Postgenomic Biology:: How Data Donation and Curation Practices Challenge the Scientific Publication System.” In Postgenomics: Perspectives on Biology after the Genome, edited by Sarah S. Richardson and Hallam Stevens, 126–49. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822375449-008. |

Net Zero Precinct Futures: place-based experimentation for sustainability transitions

On September 11, 2024, Kármán Fellow Dr Darren Sharp gave an overview of Net Zero Precincts, a four-year ARC Linkage project to develop and test a new interdisciplinary approach to help cities achieve net-zero emissions. In this interdisciplinary project, Dr Sharp aims to bring together transition management and design anthropology with the goal of transitioning to net-zero carbon emissions in an urban environment.

The starting point of the project is the Net Zero Initiative of Dr Sharp’s home institution (Monash University, Melbourne, Australia), where Monash University, as the first university in Australia, has pledged to become carbon-neutral by 2030. Net Zero Precincts is researching this transition on campus to both facilitate its success and learn lessons for scaling up such initiatives at the precinct level.

Dr Sharps started by giving overviews of the two stages of the project that are already finished. In the orienting stage, Dr Sharp and his team made use of interviews with, among others, staff, students, representatives of local and state government, and people from NGOs. The goal was to identify the main sustainability challenges, drivers, and uncertainties along the way as they were understood by the interviewees.

In the second stage, which focused on agenda-setting, workshops were used to go from abstract visions of a net-zero future by participants to concrete ideas of actionable steps and transition pathways. It was especially important at this stage to take local perspectives, the local landscape, and nature into account.

Finally, Dr Sharp briefly discussed the ongoing stage 3 of the project, which started in April 2024. Here, the pathways and visions found in stage 2 of the project were used to develop experiments for the Monash campus living lab. Different projects to overcome the identified challenges or reach the set goals are tried out.

Overall, Dr Sharp argues that the process of scaling up a net-zero project to the precinct level requires a broad perspective. It is not enough to focus on technical innovations to reduce carbon emissions alone. Instead, it is also essential to rediscover First Nations’ knowledge systems, to think about small everyday innovations, and to mobilize the community. Challenges to achieving a net-zero future are local and community-specific and must also be considered.

The Net Zero Precinct project raises fundamental questions that are also of great importance for technical universities. The self-design of universities as living labs is becoming increasingly important under the current transformative conditions of research and innovation. This is because knowledge contexts and the orientation towards socially desirable results must be intertwined with the forms of academic knowledge production. In addition, in cooperation with the Living Labs Incubator at the Human Technology Center, we were able to not only work on specific research issues in living labs in a workshop, but also discuss the first steps towards developing a global network for living lab research at universities.

Links

Net Zero Precincts: Stage 1 Report (PDF)

Net Zero Precincts: Stage 2 Report (PDF)

Photos by Jana Hambitzer