FREDERIK STJERNFELT

The midget state of “The Neutral Moresnet” on the outskirts of Aachen: a historical footnote or a political utopia?

Did you ever hear about “The Neutral Moresnet”? Neither had I, before I recently moved to Aachen close to the German border with Belgium and the Netherlands. But from my position in the North-Western edge of the city, it is less than five kilometers to this strange area. Here was located, for more than a hundred years, a midget state governed by both Germany and the Netherlands – or rather: by neither of the two.

Frederik Stjernfelt

Senior Fellow at c:o/re (10/2021-09/2022)

Frederik Stjernfelt is Professor at the Department of Communication, Aalborg University Copenhagen, Denmark. He is an author for the Danish weekly newspaper Weekendavisen, for which he wrote a longer version of this text.

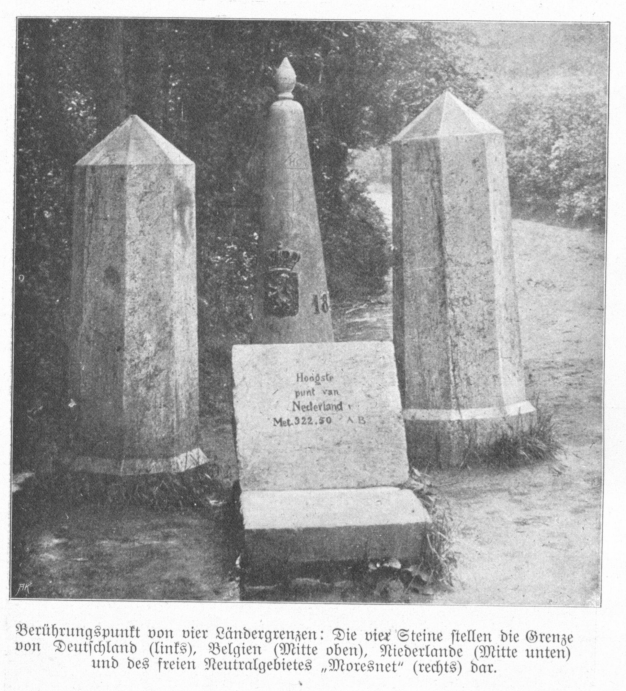

The prehistory lies with the Vienna Congress after the final defeat of Napoleon in 1814. At that time, the political borders of Europe were to be redrawn in a conservative balance of powers. One of the results was the construction of the United Netherlands as an autonomous kingdom – whose borderline to Prussia now had to be drawn. Here was a problem. In the borderland, in the small village of Kelmis, rested one of the world’s largest deposits of zinc – the village is named after the mineral calamine, zinc oxide. The interest in this metal, well fitted for many purposes such as covering the roofs of modern 19th century Paris, was increasing, and none of the two countries was willing to let the neighbor get away with the riches. The result of the negotiations was a compromise: a structure in international law known as a “condominate” – an area with shared sovereignty. Revenues from mining were shared between the Netherlands and Prussia. The Neutral Moresnet was a tiny zone, an oblong, roughly triangular pie slice; its basis rested on a couple of kilometers of the Aachen-Liège main highway, and a pointed end of 4-5 kilometers up to the the low mountains where Holland, Belgium and Germany now meet. As its legal basis the Code Napoléon applied.

An enclave based on zinc and governed by (almost) none

The administrator of the area became a mayor assigned by the two countries, and security in the small village with 256 inhabitants should be granted by one single gendarme, who, in emergency cases, would have the authority to call upon police forces from the neighboring states. In the area, “platdiets” was spoken, a dialect somewhere between Flemish and Low German. With the independence of Belgium in 1830, the new Belgian state took over responsibilities of the United Netherlands, and in the steadily growing population of the area, you could find both Germans, Belgians, Dutchmen – and “Neutrals” without any citizenship at all.

Zinc was the motor of this strange construction. The colorful entrepreneur François-Dominique Mosselman took over the business of the French engineer Jean-Jacques Dony who had secured himself a concession from Napoleon himself in 1806 to mine zinc in Kelmis . Mosselman founded the company, Vielle Montagne, in German Altenberg – that is, The Old Mountain, and invested in a comprehensive improvement of the efficiency of production. He saw to the construction of a railroad line and began importing zinc ore from all of Europe to his top modern plant in Kelmis. With the economic upswing, the population of the enclave then numbered several thousands. In reality, the “Neutral Moresnet” was a mini-state governed by a joint-stock company.

The Wild West outside of Aachen

But neutrality also gave rise to odd and surprising possibilities. None of the two constitutive countries had the right to levy duties and taxes in the area, and the prices of many goods soon sank considerably under the level of the neighboring countries. This applied to alcohol especially, and soon distilleries began to emerge in Neutral Moresnet. The population largely consisted of mine workers – men, women, and children alike – and after a hard day’s toil they cut loose and caroused in one of the 80 public houses in the minuscule area. As time went by, many of the hosts began to extend business with cabarets, and the population of a few thousand seemed to have had access to a rich cultural life of comedians, singers, dancers. Other, more shady occupations joined them: prostitution, gambling, smuggling. The gendarme, patrolling the area armed with his baton, hardly had much control over what really went on there. The smuggling of alcohol, particularly, became a strong enterprise, and myths circulate about how inhabitants might take their bicycle to work outside of the zone, every day filling up the tubes of the bicycle frame with moonshine which could now be drained and sold at expensive prices in Aachen or Liège. Neutral Moresnet also attracted draft dodgers, and girls with a higher social background who had become pregnant outside of marriage, gradually learned that you could refer to Neutral Moresnet where wet nurses were willing to take over unwanted kids for a suitable payment.

Anarchical conditions, in short, developed. Neutral Moresnet grew to a strange piece of Wild West, a tiny lawless spot outside of political control where very different types of persons might pursue happiness beyond the laws and regulations of the surrounding countries. When the exploding casinos of Europe were gradually prohibited around 1900, statelets like Monaco were quick to grasp the opportunity. This also was the case in Neutral Moresnet, and a casino was established in the hotel in Kelmis. Suddenly, the rare, new, shiny automobiles from Aachen, Liège and Maastricht could be seen flocking there. There was no law against gambling in the Code Napoléon, but in a rare display of unity, German and Belgium intervened to stop it.

Moresnet – the Seat of Friendship

The most touching events of Moresnet, however, are the utopian vistas that began to develop. The first one began as a sort of joke. In 1867 in Bruxelles, Jean-Baptiste Moens, publisher of the journal Le timbre-poste for stamp collectors, got the ingenious idea of catching his business opponent Pierre Mahé red-handed by publishing a piece of fake news in his own journal. What would be more obvious than spreading the news that the ministate of Neutral Moresnet had now begun to publish its own stamps? Mahé fell right into the trap and passed on the false news story in his journal Le timbrophile. But in a strange reversal, the joke became reality.

Already in 1883, Moresnetians began to use a flag – a tricolor with three horizontal strips of black, white, and blue. Why not publish stamps as well? Moresnet’s house doctor Wilhelm Molly founded the company of Verkehrs-Anstalt Moresnet, which published a series of eight stamps referring to Poste intérieure de Neutre Moresnet – the interior mail of the Neutral Moresnet. It might appear strange. No two houses of the area were more than two kilometers apart, and most of the inhabitants would be able to deliver their messages themselves. The stamps had no validity beyond the borders of Moresnet, in the lack of membership of international postal organizations. Was the initiative intended as a sort of political signal? In that case, Molly certainly succeeded. The Moresnet stamps gave rise to immediate anger in Bruxelles and Berlin alike. The idea, however, may also have been a personal investment for Molly. Even if Le timbre-poste scornfully made it clear that the Moresnet publications could in no sense be said to be real stamps, collectors would not be scared, and Molly’s stamps soon became valuable rarities.

But stamps were also a symptom that the Neutral Moresnet was in the process of developing a sort of political identity, a patriotism which might focus on exactly the anarchic character of the zone. In 1906, Molly met Gustave Roy who was a glowing esperantist. The period around the turn of the century was bubbling with ideas about a simple, artificial language able to transgress linguistic and cultural borders and grant world peace. Among those, Esperanto was clearly the most successful. Why not turn Neutral Moresnet into the world’s first Esperanto-speaking state? This would have made it more difficult for Belgium and Germany to cancel the autonomy of the area, such as circulating rumors were warning. Esperantist feasts, celebrations, and parades were organized, the mining company was involved, shops began to market their goods in Esperanto, even the waiters at the hotel felt obliged to learn a couple of idioms. The Esperantist World Congress in Dresden applauded and even declared that the headquarters of the movement should be transferred from Geneva to Moresnet. The Esparantist song “La Espero” was adopted as a new national anthem of Moresnet, praising internationalism and the beautiful altar of friendship to the tune of “O Tannenbaum”, and the green star of Esperantism was added to the Moresnet tricolor. The name of the new state would be “Amikejo” – The Seat of Friendship – and The Old Mountain itself bore the name of “Kvarstonoj”. Newspapers across the world reported about the project. Moresnet was increasingly referred to as a state in its own right in international media. But Bruxelles was not enthused, Berlin even less. Moresnetians organized delegations to King and Emperor in the two cities in a vain hope to protect their autonomy.

In the end, the Germans turned off the electricity. The new director of the Vieille Montagne, Charles Timmerhans, in 1913 had to go begging at the German government representative in Aachen – residing in Schinkel’s palace on Theaterstrasse 14, now the RWTH’s seat of the Human Technology Center (HumTec). Timmerhans did not succeed, however, to persuade the Germans to turn on the light switch so that zinc production could be resumed. The Germans wanted to cut the area into two, once and for all. But all these negotiations were swiftly overtaken by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. As of 1920, the now 5.000 inhabitants of Moresnet became Belgians. The bloody repetition of military events across the area in the Second World War did not change this outcome, even if the post-war period made coffee a new lucrative item for smuggling in Moresnet. One hundred years of anarchy had ended.

Shining example Moresnet?

Is there anything to be learnt from the curious example of Moresnet? The American investor and anarcho-libertarian Peter C. Earle thinks: yes. In his booklet A Century of Anarchy, Earle declares himself a revisionist and presents the argument that the example of Moresnet goes to show that peace and prosperity is possible without force, without state, without government. In the absence of high taxation and export-import control, the enclave of Moresnet became prosperous, and the inhabitants managed to solve disputes in a flexible way with the mayor and gendarme, Earle claims. One would like, however, to have access to a credible criminal statistics of the area. Earle refers to the traditional urge for liberty among mountain people – even if the rugged and mountainous character of the area, truth be told, is rather limited and rather amounts to sweet rolling hills. Not only must it be said that Eales does not testify to any more close knowledge of the history of the enclave – he also overlooks the special boundary conditions of the area. Its prosperity basically had its roots in the presence of a rich zinc vein and related international investments, plus smuggling and other shady businesses – while railroads, electricity, mail, telephone, security were taken care of by the two conflicting protecting powers. The Dutch author Philip Dröge’s small bestseller Moresnet (German: Niemands Land) is a more thorough source of information about the area – from which the present small article has benefited.

If you take a trip to Moresnet today, you must sharpen your gaze to catch a glimpse of the traces of the glorious days of neutrality. There is a fine small museum in the former railway station, but the old industrial architecture is long gone, and the large open mine has been filled up. There are no longer 80 pubs, but there is no lack of serving establishments, and the delicious and hearty Belgian cuisine cannot be denied, e.g. at the Auberge de Moresnet to which I can offer my best recommendations. In 2020, the last “neutral” died, the 105-years old Catharina Meessen. Might Moresnet, in a parallel world, have survived like San Marino, Andorra, Athos, or other strange bunions on the map of Europe? With its 3½ square kilometers, Moresnet boasts almost the double area of Monaco. An economy of philatelists, history buffs, casinos, tourism, alcohol, plus a Michelin restaurant or two, might it have attracted sufficiently many – here, only one hour of driving form Bruxelles or Cologne, ten minutes from Aachen, maybe also attracting speculators and tax fraudsters like the Channel Islands?

This would hardly, however, have realized the more ambitious political visions of the Neutral Moresnet.

References

Peter C. Earle. 2014. A Century of Anarchy: Neutral Moresnet through the Revisionist Lens, Intangible Goods.

https://www.mindat.org/loc-304.html

https://www.trois-frontieres.be/D/moresnet_neutre.php

Philip Dröge. 2017. Niemands Land: Die unglaubliche Geschichte von Moresnet, einem Ort, den es eigentlich gar nicht geben durfte. München: Piper Verlag.

Featured image: Map of the municipality Moresnet, 1868; LAV NRW R, RW-Karten 6317.

proposed citation: Stjernfelt, Frederik. 2022. The Long Summer of Anarchy on the Old Mountain. https://khk.rwth-aachen.de/2022/02/02/2311/2311/