ARIANNA BORRELLI

The Symposium Computer in Motion critically questioned the notion of the computer as a “universal machine” by demonstrating how the computer adapted to and was appropriated in different milieus, cultures, communities and across borders. By historicising the movement of computer-related knowledge and artifacts, the presentations help us recover multiple sites of agency behind the idea of an unstoppable digital transformation driven by capitalist innovation. The event was organized by Barbara Hof (University of Lausanne) Ksenia Tatarchenko (John Hopkins University) and Arianna Borrelli (c:o/re RWTH Aachen) on behalf of the Division for History and Philosophy of Computing (HaPoC) in context of the 27th International Conference of History of Science and Technology, held at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, and online from June 29 to July 5 2025.

The Symposium had an exceptional coverage of periods and cultures, showcased here as an example of the manifold thematic and methodological facets of the history of computing..

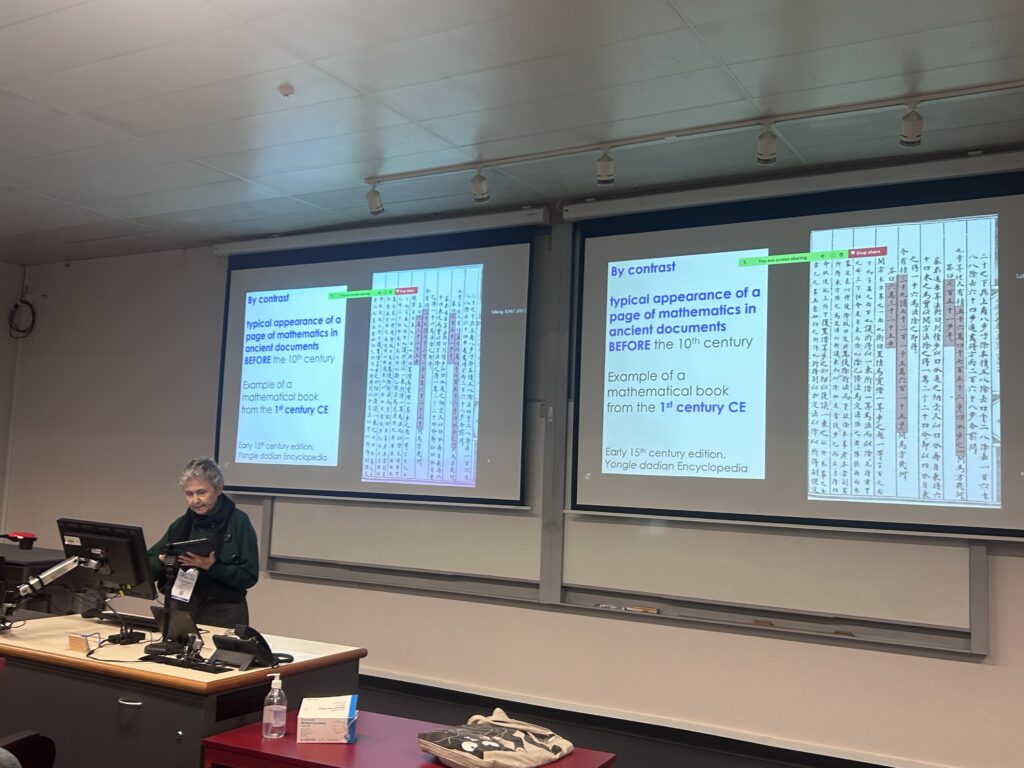

Decimal place-value notations prior to the 10th century: a material computer

Karine Chemla (School of Mathematics, University of Edinburgh, and researcher emerita CNRS)

This presentation argues that decimal place-value notations have been introduced as material tools of computation and that, until around the 10th century, they were used only as a material notation to compute, and were never shown in illustrations in mathematical writings, let alone used to express numbers. Furthermore, the presentation argues that the same remarks hold true whether we consider the earliest extant evidence for the use of such a numeration system in Chinese, Sanskrit, and Arabic sources. In all these geographical areas, decimal place-value numeration systems were first used as a material notation. These remarks suggest that, as a tool of computation, decimal place-value numeration systems have circulated in the context of a material practice, despite changes in the graphics for the digits, and changes in the materiality of the computation.

Smuggling Vaxes: or how my computer equipment was detained at the border

Camille Paloque-Bergès (Laboratoire HT2S, Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers)

Between 1980 and 1984, the global computer market was heavily influenced by rising DEFCON levels and industrial espionage, alongside the imposition of restrictions on US computer equipment exports (Leslie, 2018). One notable example was the VAX mini-computer from DEC, which became subject to the COCOM doctrine, restricting its distribution due to its strategic importance. Popular in research communities, the VAX supported the Unix operating system and played a pivotal role in the development of Arpanet and the UUCP networks, both precursors to the modern Internet. Despite restrictions, the VAX was widely imported through workarounds or cloning techniques. This paradox of open-source R&D efforts occurring within a politically closed environment (Russell, 2013; Edwards, 1996) is illustrated by the infamous “Kremvax” joke on Usenet, which falsely claimed the USSR had joined the Internet. The study of the VAX’s role in both Eastern and Western Europe highlights the tension between technological openness and Cold War-era containment policies. These technical and administrative maneuvers, though trivial to the broader public, were crucial for the diffusion and cultural adoption of early data networks at the level of the system administrator working in a computer center eager to become a network node.

A Thermal History of Computing

Ranjodh Singh Dhaliwal (University of Basel) ranjodhdhaliwal.com

If you open a computer today, the biggest chunk of real estate, curiously, is not taken by processors, memories, or circuit boards but by increasingly complex heat sinks. Starting from this observation that all technology today needs extensive heat management systems, this piece theorizes the historical and conceptual dimensions of heat as it relates to computing. Using case studies from the history of computation–including air conditioning of the early mainframe computers running weather simulations (such as ENIAC in IAS in the 1960s) and early Apple machines that refused to run for long (because Steve Jobs, it is said, hated fans)–and history of information–the outsized role of thermodynamics in theorizing information, for example–I argue that computation, in both its hardware and software modalities, must be understood not as a process that produces heat as a byproduct but instead as an emergent phenomenon from the heat production unleashed by industrial capitalism.

Put another way, this talk narrates the story of computation through its thermal history. By tracing the roots of architectural ventilation, air conditioning of mainframes and computer rooms in the 20th century, and thermodynamics’ conceptual role in the history of information and software, it outlines how and why fans became, by volume, the biggest part of our computational infrastructures. What epistemological work is done by the centrality of heat in these stories of computation, for example, and how might we reckon with the ubiquitization of thermal technologies of computing in this age of global climate crises?

Supercomputing between science, politics and market

Arianna Borrelli (Käte-Hamburger-Kolleg “Cultures of Research” RWTH Aachen)

Since the 1950s the term “supercomputer” has been used informally to indicate machines felt to have particularly high speed or large data-handling capability. Yet it was only in the 1980s that systematic talk of supercomputers and supercomputing became widespread, when a growing number of supercomputing centers were established in industrialized countries to provide computing power mainly, but not only, for fundamental and applied research. Funding for creating these institutes came from the state. Although arguably at first these machines could be of use only in a few computationally-intensive fields like aerodynamics or the construction of nuclear power plants, sources suggest that there were also scientists from other areas, especially physicists, who promoted the initiative because they regarded increasing computing power as essential for bringing forward their own research. Some of them also had already established contacts with computer manufacturers. In my paper I will discuss and broadly contextualize some of these statements, which in the 1990s developed into a wide-spread rhetoric of a “computer revolution” in the sciences.

Neurons on Paper: Writing as Intelligence before Deep Learning

David Dunning (Smithsonian National Museum of American History)

In their watershed 1943 paper “A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity,” Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts proposed an artificial neural network based on an abstract model of the neuron. They represented their networks in a symbolism drawn from mathematical logic. They also developed a novel diagrammatic system, which became known as “McCulloch–Pitts neuron notation,” depicting neurons as arrowheads. These inscriptive systems allowed McCulloch and Pitts to imagine artificial neural networks and treat them as mathematical objects. In this manner, they argued, “for any logical expression satisfying certain conditions, one can find a net behaving in the fashion it describes.” Abstract neural networks were born as paper tools, constituting a system for writing logical propositions.

Attending to the written materiality of early neural network techniques affords new historical perspective on the notoriously opaque technology driving contemporary AI. I situate McCulloch and Pitts in a material history of logic understood as a set of practices for representing idealized reason with marks on paper. This tradition was shot through with anxiety around the imperfection of human-crafted symbolic systems, often from constraints as mundane as “typographical necessity.” Like the authors they admired, McCulloch and Pitts had to compromise on their notation, forgoing preferred conventions in favor of more easily typeset alternatives. Neural networks’ origin as inscriptive tools offers a window on a moment before the closure of a potent black box, one that is now shaping our uncertain future through ever more powerful, ever more capitalized deep learning systems.

Knowledge Transfer in the Early European Computer Industry

Elisabetta Mori (Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona)

The collaboration with an academic mathematical laboratory or research institute is a recurring pattern in the genesis of early computer manufacturers: it typically involved financial support and exchanges of patents, ideas and employees.

In my presentation I show how knowledge transfer between academic laboratories and private corporations followed different strategies and was shaped by the contingent policies and contexts in which they unfolded. The presentation focuses on three different case studies: the partnership between the Cambridge Mathematical Laboratory and Lyons, begun in 1947; the example of the Mathematisch Centrum in Amsterdam and its 1956 spin-off NV Electrologica; and the case of the Matematikmaskinnämnden and Facit, the Swedish manufacturer of mechanical calculators, which entered the computer business in 1956.

The three case studies are representative of three distinct patterns. First, knowledge transfer by a sponsorship agreement. Funding and supporting the construction of the EDSAC computer enabled the Lyons catering company (a leader in business methods) to appropriate its design to manufacture its LEO Computers. Second, knowledge transfer through a spin-off. Electrologica (the Netherland’s first computer manufacturer) was established by computer scientists of the Mathematisch Centrum as a spin-off to commercialize the computers designed by the institute. Third, the recruitment of technical staff from a center of excellence. Facit entered the computer business by hiring most of its technicians and researchers from Matematikmaskinnämnden (the research organization of the Swedish government). Taken together the three case studies cast light on how R&D diffused in the embryonic computer industry in post-war Europe.

A commission and its nationalist technicians: expertise and activities in the Brazilian IT field in the 1970s

Marcelo Vianna (Federal Institute of Education Science and Technology of Rio Grande do Sul)

The history of Brazilian IT in the 1970s is influenced by the work of a group of specialists who occupied spaces in university and technocratic circles to propagate ideas of technological autonomy from the Global North. In this sense, there is a consensus that an elite of this group, acting in the Commission for the Coordination of Electronic Processing Activities (CAPRE), managed to establish a national Informatics policy, giving rise to an indigenous computer industry at the end of the decade. However, there is still much to be explored about the dynamics surrounding CAPRE’s different activities and the profile of its “ordinary” technicians, considering the breadth of attributions that the small body assumed in structuring the Brazilian IT field. Our proposal is to map them by combining prosopography and identifying the concepts, cultures and practices that guided its actions, such as the ideas of “rationalization” and “technological nationalism” and the establishment of a technopolitical network with the technical-scientific community of the period, including the first political class associations in the field of Computer Science. The paper will discuss the composition of the group and its expertise and trajectories, as well as the main actions of the technicians aimed at subsidizing CAPRE’s decision-makers. In this sense, the considerable degree of cohesion between technicians and its leaders ensured that an autonomous path was established for Informatics in the country, even though they were exposed to the authoritarian context of the period, which led to CAPRE itself being extinguished in 1979.

People of the Machine: Seduction and Suspicion in U.S. Cold War Political Computing

Joy Rohde (University of Michigan)

The computational social scientific projects of the Cold War United States are known for their technocratic and militarized aspirations to political command and control. Between the 1960s and the 1980s, Defense officials built systems that sought to replace cognitively limited humans with intelligent machines that claimed to predict political futures. Less familiar are projects that sought to challenge militarized logics of command and control. This paper shares the story of CASCON (Computer-Aided System for Handling Information on Local Conflicts), a State Department-funded information management system that mobilized the qualitative, experiential knowledge and political acumen of diplomats to challenge U.S. Cold War logics, like arms trafficking and unilateral interventionism. The system’s target users—analysts in the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency and the State Department tasked with monitoring conflicts in the global South—were notoriously skeptical of the Pentagon’s militarism and computational solutionism. Yet users ultimately rejected the system because it did tell them what to do! Despite their protestations, they had internalized the command and control logics of policy computing.

CASCON was an early effort to design around the contradictions produced by coexisting fears of human cognitive and information processing limits, on the one hand, and of ceding human agency and expertise to machines on the other. I conclude by arguing that CASCON reflects the simultaneous seduction and fear of the quest to depoliticize politics through technology—an ambivalence that marks contemporary computing systems and discourse as well.

AI in Nomadic Motion: A Historical Sociology of the Interplay between AI Winters and AI Effects

Vassilis Galanos (University of Stirling)

Two of the most puzzling concepts in the history of artificial intelligence (AI), namely the AI winter and the AI effect are mutually exclusive if considered in tandem. AI winters refer to the phenomenon of loss in trust in AI systems due to underdelivery of promises, leading to further stagnation in research funding and commercial absorption. The AI effect suggests that AI’s successful applications have historically separated themselves from the AI field by the establishment of new/specialised scientific or commercial nomenclature and research cultures. How do AI scientists rebrand AI after general disillusionment in their field and how do broader computer science experts brand their research as “AI” during periods of AI hype? How does AI continue to develop in periods of “winter” in different regions’ more pleasant climates? How do periods of AI summer contribute to future periods of internet hype during their dormancy? These questions are addressed drawing from empirical research into the historical sociology of AI, a 2023 secondary analysis between technological spillages and unexpected findings for internet and HCI research during periods of intense AI hype (and vice versa, AI advancements based on periods of internet/network technologies hype), as well as a 2024 oral history project on AI at Edinburgh university and the proceedings of the EurAI Workshop on the History of AI in Europe during which, several lesser known connections have been revealed. To theorise, I am extending Pickering/Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of nomadic science previously applied to the history of mathematics and cybernetics.

Vector and Raster Graphics : Two Pivotal Representation Technologies in the Early Days of Molecular Graphics

Alexandre Hocquet and Frédéric Wieber (Archives Poincaré, Université de Lorraine), Alin Olteanu (Shanghai University), Phillip Roth (Käte-Hamburger-Kolleg “Cultures of Research” RWTH Aachen)

https://poincare.univ-lorraine.fr/fr/membre-titulaire/alexandre-hocquet

Our talk investigates two early computer technologies for graphically representing molecules – the vector and the raster display – and traces their technical, material, and epistemic specificity for computational chemistry, through the nascent field of molecular graphics in the 1970s and 1980s. The main thesis is that both technologies, beyond an evolution of computer graphics from vector to raster displays, represent two modes of representing molecules with their own affordances and limitations for chemical research. Drawing on studies in the media archaeology of computer graphics and in history of science as well as primary sources, we argue that these two modes of representing molecules on the screen need to be explained through the underlying technical objects that structure them, in conjunction with the specific traditions molecular modeling stems from, the epistemic issues at stake in the involved scientific communities, the techno-scientific promises bundled with them, and the economic and industrial landsape in which they are embedded.

Erring Humans, Learning Machines: Translation and (Mis)Communication in Soviet Cybernetics and AI

Ksenia Tatarchenko (John Hopkins University)

This paper centers on translation in Soviet cybernetics and AI. Focusing on cultural practices of translation and popularization as reflected in widely-read scientific and fictional texts, I interrogate practices of interpretation in relation to the professional virtue of scientific veracity as well as its didactic function in the Soviet cybernetic imaginary throughout the long Thaw. The publication of the works of Norbert Wiener, Alan Turing, and John von Neumann in Russian was not simply aimed at enabling direct access to the words and thoughts of major bourgeois thinkers concerned with automation and digital technologies: translating and popularizing cybernetics in the post-Stalinist context was about establishing new norms for public disagreement. No longer limited to the opposition of true and false positions, the debates around questions such as “Can a machine think?” that raged across a wide spectrum of Soviet media from the late 1950s to the 1980s were framed by an open-ended binate of what is meaningful or, on the contrary, meaningless. In his classic 1992 book The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity, Anson Rabinbach demonstrates how the utopian obsession with energy and fatigue shaped social thought in modern Europe. In a similar line, this project explores how human error takes on a new meaning when the ontology of information central to Western cybernetics is adopted to a Soviet version of digital modernity.

Tech Disruptors, Then and Now

Mar Hicks (University of Virginia)

This paper explores the connected histories of whistleblowers and activists who worked in computing from the 1960s through the present day, showing how their concerns were animated by similar issues, including labor rights, antiracism, fighting against gender discrimination, and concerns regarding computing’s role in the military-industrial complex. It looks at people who tried to fight the (computer’s) power from within the computing industry, in order to write an alternative history of computing.

Nosebleed Techno, Sound Jams and Midi Files: the Creative Revolution of Australian Musicians in the 1990s through AMIGA Music Production.

Atosha McCaw (Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne)

This paper looks at the innovative use of the AMIGA computer by Australian musicians in the 1990s, highlighting its role as a cost-effective tool for music production, experimentation, and collaboration. By examining how these artists harnessed the power of this technology to share files and rapidly materialize creative concepts, we uncover a fascinating chapter in the evolution of electronic music in Australia.

Computers and Datasets as Sites of Political Contestation in an Age of Rights Revolution: Rival Visions of Top-Down/Bottom-Up Political Action Through Data Processing in the 1960s and 1970s United States

Andrew Meade McGee (Smithsonian Air and Space Museum)

As both object and concept, the electronic digital computer featured prominently in discussions of societal change within the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. In an era of “rights revolution,” discourse on transformative technology paralleled anxiety about American society in upheaval. Ever in motion, shifting popular conceptualizations of the capabilities of computing drew comparisons to the revolutionary language of youth protest and the aspirations of advocacy groups seeking full political, economic, and social enfranchisement. The computer itself – as concept, as promise, as installed machine – became a contested “site of technopolitics” where political actors appropriated the language of systems analysis and extrapolated consequences of data processing for American social change. Computers might accelerate, or impede, social change.

This paper examines three paradigms of the computer as “a machine for change” that emerge from this period: 1) One group of political observers focused on data centralization, warning of “closed worlds” of institutional computing that might subject diverse populations to autocratic controls or stifle social mobility; 2) In contrast, a network of social activists and radicals (many affiliated with West Coast counterculture and Black Power movements) resisted top-down paradigms of data centralization and insisted community groups could seize levers of change by embracing their own forms of computing. 3) Finally, a third group of well-meaning liberals embraced the potential of systems analysis as a socially-transformative feedback loop – utilizing the very act of data processing itself to bridge state institutions and local people, sidestepping ideological, generational, or identity-based conflict.

Computing a Nation: Science-Technology Knowledge Networks, Experts, and the Shaping of the Korean Peninsula (1960-1980)

Ji Youn Hyun (University of Pennsylvania)

This paper presents a history of the ‘Systems Development Network’ (SDN), the first internet network in Asia established in 1982, developed in South Korea during the authoritarian presidency of Park Chung-Hee (1962-1979). I examine scientists and engineers who were repatriated under Park’s Economic Reform and National Reconstruction Plan to reverse South Korea’s ‘brain-drain’, re-employed under government sponsored research institutions, and leveraged to modernize state industrial manufacturing.

Pioneered by computer scientist Kilnam Chon, often lauded as ‘the father of East Asia’s internet’, a transnationally trained group of experts at the Korea Institute of Electronics Technology (KIET) developed the nation’s internet infrastructure, despite repeated government pushback and insistence on establishing a domestic computer manufacturing industry. Drawing on the Presidential Archive and National Archives of Korea, I describe how the SDN manifested through a lineage of reverse-engineering discarded Cheonggyecheon black market U.S. Military Base computer parts, prototyping international terminal and gateway connections, and “extending the instructional manual” of multiple microprocessors.

The reconfiguration of computer instructional sets are one of many cases of unorthodox, imaginative, and off-center methods practiced in Korea to measure up and compete with Western computing. Although repatriated scientists were given specific research objectives and goals, their projects fundamentally materialized through a series of experimental and heuristic processes. This paper will illuminate South Korea’s computing history, which until now has not been the subject of any history, and also allow a broader reflection on the transformation of East Asia during the Cold War––highlighting political change through the development of computing.

Collecting Data, Sharing Data, Modeling Data: From Adam and Eve to the World Wide Web within Twenty Years

Barbara Hof (University of Lausanne)

Much like physicists using simulations to model particle interactions, scientists in many fields, including the digital humanities, are today applying computational techniques to their analysis and research and to the study of large data sets. This paper is about the emergence of computer networks as the historical backbone of modern data sharing systems and the importance of data modeling in scientific research. By exploring the history of computer data production and use in physics from 1990 back to 1970, when the Adam & Eve scanning machines began to replace human scanners in data collection at CERN, this paper is as much about retelling the story of the invention of the Web at CERN as it is about some of the technical, social and political roots of today’s digital divide. Using archival material, it argues that the Web, developed and first used at physics research facilities in Western Europe and the United States, was the result of the growing infrastructure of physics research laboratories and the need for international access to and exchange of computer data. Revealing this development also brings to light early mechanisms of exclusion. They must be seen against the backdrop of the Cold War, more specifically the fear that valuable and expensive research data at CERN could be stolen by the Soviets, which influenced both the development and the restriction of data sharing.

Differing views of data in Aotearoa: the census and Māori data

Daphne Zhen Ling Boey and Janet Toland (Victoria University of Wellington | Te Herenga Waka)

This presentation explores differing concepts of “data” with respect to the Indigenous Māori people of Aotearoa and colonial settlers. A historical lens is used to tease out long-term power imbalances that still play out in the data landscape today. Though much data has been collected about Māori by successive governments of New Zealand, little benefit has come to Māori themselves.

This research investigates how colonisation impacted Māori, and the ongoing implications for data. The privileging of Western approaches to harnessing the power of data as opposed to indigenous ways stems from colonisation – a system that results in “a continuation of the processes and underlying belief systems of extraction, exploitation, accumulation and dispossession that have been visited on Indigenous populations.”

We examine the census, an important tool that provides an official count of the population together with detailed socioeconomic information at the community-level and highlight areas where there is a fundamental disconnect between the Crown and Māori. Does Statistics New Zealand, as a Crown agency, have the right to determine Māori ethnicity, potentially undermining the rights of Māori to self-identify? How do differing ways of being and meaning impact how we collect census data? How does Aotearoa commit to its Treaty obligations to Māori in the management and optimisation of census data? We also delve into Māori Data Sovereignty, and its aim to address these issues by ensuring that Māori have control over the collection, storage and use of their own data as both enabler of self-determination and decolonisation.

History of computing from the perspective of nomadic history. The case of the hiding machine

Liesbeth De Mol (CNRS, UMR 8163 Saviors, Textes, Langage, Université de Lille)

Computing as a topic is one that has moved historically and methodologically through a variety of disciplines and fields. What does this entail for its history? The aim of this talk is to provoke a discussion on the future of the history of computing. In particular, I use a notion of so-called nomadic history. This is in essence the idea to identify and overcome ones own disciplinary and epistemological obstacles by moving across a variety of and sometimes conflicting methods and fields. I apply the method to the case of the history of the computer-as-a-machine which is presented as a history of hide-and-seek. I argue that the dominant historical narrative in which the machine got steadily hidden away behind layers of abstraction needs countering both historically as well as epistemologically. It is based on a collaboratively written chapter for the forthcoming book “What is a computer program?”.

Modeling in history: using LLMs to automatically produce diagrammatic models synthesizing Piketty’s historiographical thesis on economic inequalities

Axel Matthey (University of Lausanne)

This research integrates theoretical digital history with economic history. Employing Large Language Models, we aim to automatically produce historiographical diagrams for analysis. Our experience with the manual production of historiographical diagrams suggests that LLMs might be useful to support the automatic generation of such historiographical diagrams which aim at facilitating the visualization and understanding of complex historical narratives and causal relationships between historical variables. Our initial exploration involved using Google’s LLM (Gemini 1.5 Pro) and OpenAI’s GPT-4o to convert a concise historical article by Piketty into a simplified causal diagram. This article is A Historical Approach to Property, Inequality and Debt: Reflections on Capital in the 21st Century . LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in various domains, including understanding and generating code, translating languages, and even creating different creative text formats. We show that LLMs can be trained to analyze historical texts, identify causal relationships between concepts, and automatically generate corresponding diagrammatic models. This could significantly enhance our ability to visualize and comprehend complex historical narratives, making implicit connections explicit, and facilitating further exploration and analysis. Historiographical theories explore the nature of historical inquiry, focusing on how historians represent and interpret the past: in this research, the use of diagrams is being considered as a means to enhance the communication, visualization, and understanding of these complex theories.

Computational Illegalism

Luke Stark (Western University Canada)

In his analysis of the concept in his lectures on the development of the “punitive society,” Michel Foucault describes the eighteenth century as a period of “systematic illegalism,” including both lower-class or popular illegalism and “the illegalism of the privileged, who evade the law through status, tolerance, and exception” (Foucault 2015, 142). In this paper, I argue that illegalism has new utility as an analytic concept in the history of computing. Illegalism is a characteristic of both the business models and rhetorical positioning of many contemporary digital media firms. Indeed, such “computational illegalism” is so rife that commentators often seem to accept it as a necessary aspect of Silicon Valley innovation.

In this presentation, I describe illegalism as theorized by Foucault and others and develop a theory of platform illegalism grounded in the history of technical and business models for networked computing since the 1970s. This presentation is part of a larger project in which I document the prevalence of illegalism on the part of digital platforms in various arenas, focusing in particular on platform labor and generative AI; examine the range of responses to such illegalism from consumers, activists, and governments; and formulate recommendations regarding ways to account for platform illegalism in scholarly and activist responses as part of governance mechanisms for digitally mediated societies.

The datafied “enemy,” Computational work, and Japanese American incarceration during World War II

Clare Kim (University of Illinois Chicago)

Following the events of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, a series of U.S. presidential proclamations and executive orders authorized the legal designation and treatment of people of Japanese ancestry as “enemy aliens.” The designation of the US West Coast as military zones under Executive Order 9066 enabled the removal and subsequent incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps. The problem of identifying, incarcerating, and managing Japanese enemy alien populations necessitated the treatment of these military zones and spaces as information environments, where the classification of Japanese and Japanese American residents as enemy alien, citizen, or an alternative subject position could be adjudicated. This paper explores how conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II contoured the entanglements between computational work and Asian and Asian Americans residing in the U.S., recounting the setup of statistical laboratories established to track and manage Japanese American incarceration. It reveals how datafication practices were collapsed and equated with bodies that were racialized as an enemy alien and yellow peril, which paradoxically effaced other subject positions to which Japanese Americans came to occupy at the time: in particular, the invisible labor to which they furnished to statistical work as technical experts themselves.

Header photo credits: Elisabetta Mori