BERND BÖSEL

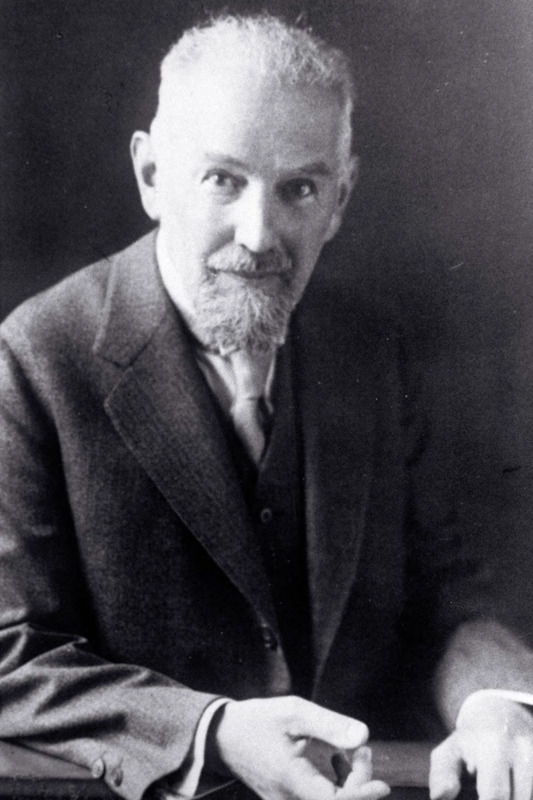

In the first decades of the 20th century, psychology was still a young academic discipline that, in contrast to the well established field of psychiatry, had not yet fully emancipated from its origins in philosophy. It still felt the need to prove that the production of psychological knowledge paid off for society at large. This was accomplished by what back then was called »psychotechnics«, a term first coined by the German psychologist William Stern in 1903 in an article that also introduced the notion of »applied psychology«. Stern was instrumental in establishing the idea that psychology could be used for extra-psychological goals, such as the advancement of culture at large. However, it was Hugo Münsterberg who turned »psychotechnics« into a catch-all phrase for applied psychological methods.

Bernd Bösel

c:o/re Fellow 04/25 – 03/26

Bernd Bösel is a philosopher and media scholar. His main area of research are the technical and digital operationalization of affect and emotions, as well as media theory and philosophy of technology.

Münsterberg had been offered a chair for psychology at Harvard University by none other than William James, one of the founders of psychology as an academic discipline, in the 1890s and subsequently established himself as the leading psychology professor of his generation. Due to the many books he published in English as well as his native German, he exerted an enormous influence on his discipline on either side of the Atlantic. In his textbooks Psychology – General and Applied and Grundzüge der Psychotechnik, both published in 1914, he outlined a grand vision for applying psychotechnics to literally every field of cultural activity, including law, science, pedagogy, arts, economy, the health sector and even policing. While conducting a plethora of psychological experiments in his laboratory at Harvard, he also collaborated with industrial companies and investigated the effects of work environments on attention and fatigue. Münsterberg conceived industrial psychology as a branch of psychotechnics that would eventually elevate Frederick Taylor’s Scientific Management to a truly scientific level.

During World War I, the employment of psychotechnical testing procedures proved fruitful, especially for the operation of new machinery like the aeroplane or the streetcar, but also sophisticated industrial devices for which best practices had yet to be established. This was the birthplace of »industrial psychotechnics« which became an international success in the 1920s, during which a number of institutes and journals for psychotechnics were founded. The »International Association of Psychotechnics« organized eight conferences between 1920 and 1934. However, in the early 1930s psychotechnics was already in a deep and long-lasting crisis that had started with the Great Crash of 1929. But there were not just economic, but also political reasons for the demise of industrial psychotechnics. In Nazi Germany, the persecution of what was defined as »Jewish« scientists led to a weakening of psychotechnical research (William Stern was dismissed from his chair in Hamburg and soon after fled to the US, while two of his assistants committed suicide). In the USSR, following a decade of wide-ranging experimentation that combined psychotechnics with architecture, film, and human physiology, the Stalinist purges effectively ended all of these activities.

After World War II had ended, the International Association of Psychotechnics reconvened in 1949 in Bern. The demand for applied psychology soon skyrocketed due to the mental health crisis caused by the devastations of the war. In 1955, the Association renamed itself to »International Association of Applied Psychology«, thus erasing the term »psychotechnics« from its self-description. This has led historians of psychology to the conclusion that psychotechnics was discontinued and had become a thing of the past. But what if we question this conclusion and rather focus on the continuities in the way that applied psychology, as an academic discipline, seeks to improve its understanding of psychological processes, and to ultimately develop optimal methods of influencing the human mind? It could be argued that the success story of applied psychology in the second half of the 20th century, with its branching out into ever more specialized subfields (e. g. behavioral economics, sport psychology, or environmental psychology), equals the realization of Hugo Münsterberg’s aim to bring psychotechnics to every aspect of human life and culture.

In regard to our contemporary digital lifeworld, there is an even greater urgency to reactivate the semantics of »psychotechnics«. Scholars working in the field of media studies and philosophy of technology have proposed the term »psychotechnology« as a label for media and information technologies altogether. The reason is that these technologies, just by the way of their functioning, captivate our attention and influence our affective lives. Digital gadgets also increasingly organize our memory, our imaginations as well as our wishes and desires. These technological developments are coincidental with the global rise of applied psychology for a good reason. As a matter of fact, psychology and computation have been converging for a long time, as the history of cybernetics shows.

Today, Big Tech companies employ psychologists to get a better understanding of how their customers think and feel and how to make them »addicted by design«. Scraping personal data assists in the goal of micro-targeting individual users. What has critically been described as surveillance capitalism, data capitalism or just digital capitalism thus operates on a psychotechnological basis. It has yet to be determined how many of these developments can be traced back to the early conceptions of psychotechnics outlined by Stern, Münsterberg and their colleagues. In any case, instead of upholding the idea that psychotechnics is a thing of the past, we should engage with its surprising afterlife. Through the increasing automation of measuring and operating psychic functions, what began as an expert-based psychotechnics is now more and more being accomplished by technical systems that are being constantly updated and expanded by companies that do not always adhere to ethical standards. Therefore, we should come to a better understanding of the design principles and overall goals involved. A critical theory of

contemporary psychotechnologies will be an important cornerstone in our collective effort to save democracy and human dignity and freedom.