At the KHK c:o/re, the practice of artistic research has always been part of our research interests. For this reason, we invite fellows working closely with the arts in each fellow cohort. In the past four years, we have realized various projects in collaboration with art scholars and practitioners, and different cooperation partners, ranging from artistic positions in the form of performance, installation, discourse, and sound. Many of these events were part of the center’s transfer activities to make the research topics and interests visible, relatable, and tangible. In this sense, art can be seen as a translation for scientific topics. But the potential of the interaction between science and art doesn’t end there. Art is more than a tool for science communication, it is a research culture. Therefore, we ask the following questions: What kind of knowledge is generated in artistic production? How are these types of knowledge lived in artistic research? And, in combination with one of the central research fields of the center: To what extent are artistic approaches methodologies for what we understand as expanded science and technology studies?

To get closer to answering these questions, we talked to some of our fellows who are working closely with the arts and researching the connection between science and art. We want to find out about the epistemic value of artistic research, the methodologies and institutional boundaries of artistic research in an academic environment, and how they implement artistic research in their research areas.

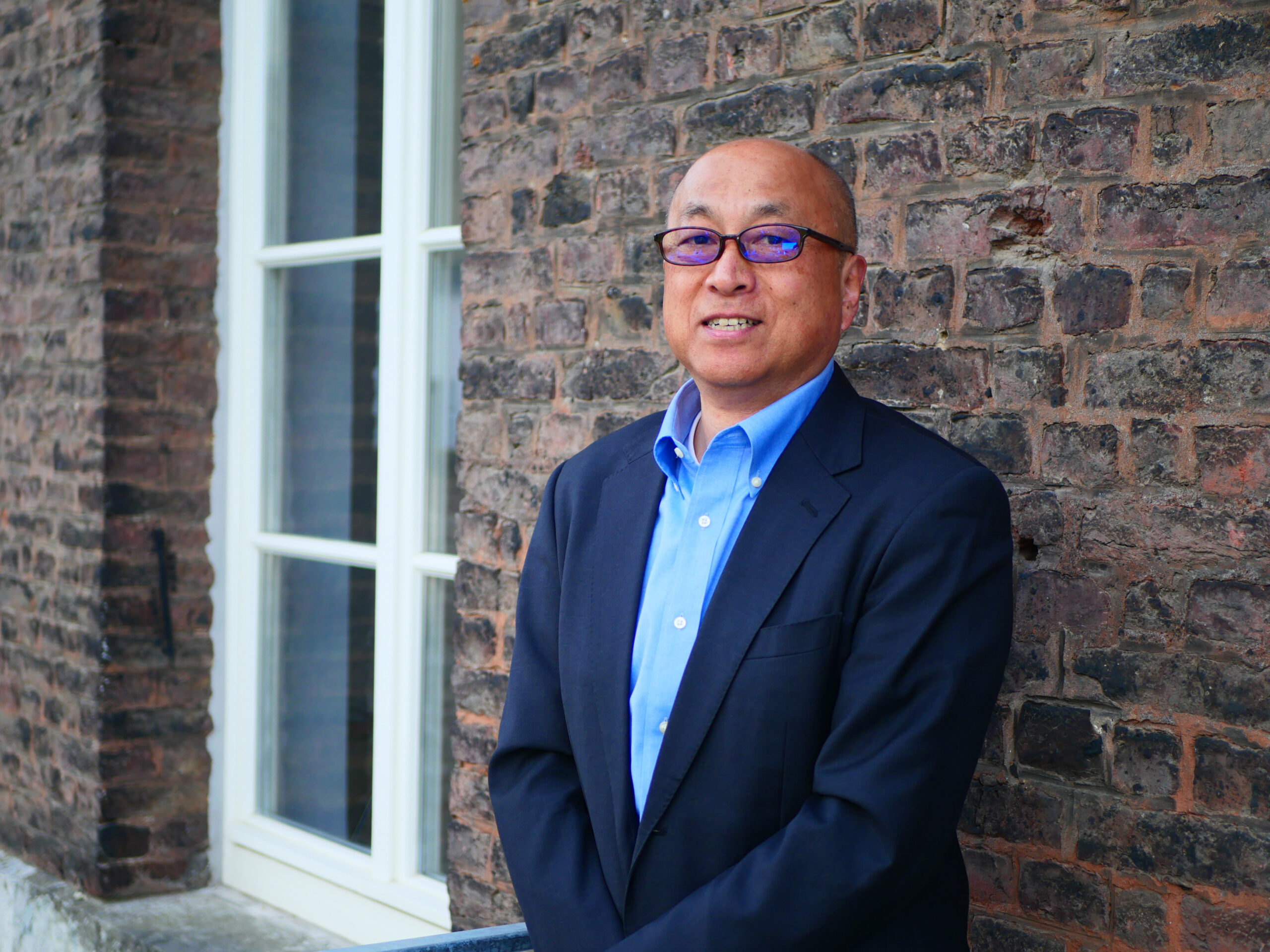

In this edition of the interview series, we spoke to KHK c:o/re alumni fellow Masahiko Hara.

Masahiko Hara

Masahiko Hara is an engineer and Professor Emeritus of Tokyo Tech, Japan. His research interests are in the areas of Nanomaterials, Nanotechnology, Self-Assembly, Spatio-Temporal Fluctuation and Noise, Ambiguity in Natural Intelligence, Bio-Computing, Chemical Evolution, Origins of Life, and Science and Art Installation.

KHK c:o/re: What do you think is the epistemological value of artistic research?

Masahiko Hara: Artistic research expands the diversity of “knowing” by exploring sensory and embodied experiences, as well as aspects of “tacit knowledge” that are difficult to verbalize. It offers an alternative approach to phenomena that cannot be fully grasped by the theories and data-driven frameworks centered on “explicit knowledge”, which are prioritized in contemporary science and technology.

Historically, philosophy and physics (here referring to the natural sciences) were two sides of the same coin. However, as they developed separately in the 20th century, there arose a need for a new metaphysics — a kind of metaphysical translation that could bridge the gap. I believe this is where the value of artistic research lies:

- Contribution to diverse forms of knowledge

- Reframing how questions are asked

- Critically reflecting on how we know

- Emphasizing experience and relationality

What specific methodologies are used in artistic research? Can you give an example?

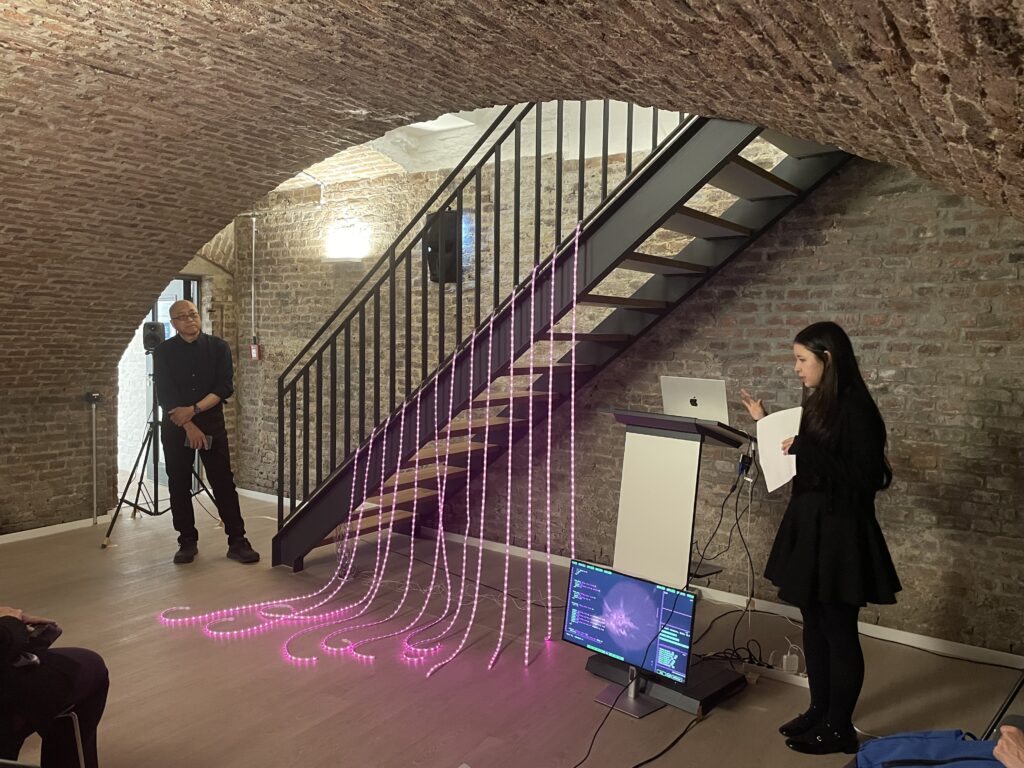

Certainly, I believe the science-art installation experiments we are conducting represent a cutting-edge methodology in artistic research. Other examples include performances, participatory projects, and experimental creations using bio-materials, for example.

I have conducted “scientist-in-residence” projects that explore experimental creation at the intersection of science and art — such as computation using slime mold amoebas and experiments on crowd psychology and social group dynamics. Each of these projects is still in a “prototype” phase, but I feel that this very process of trial and error itself constitutes a new methodology.

How do product-oriented art forms such as exhibitions or installations differ from process-oriented approaches to art? Is there a hierarchy? How do these approaches influence each other?

Product-oriented approaches focus on a “finished form” to be delivered to the audience, while process-oriented approaches value the creative process and trial-and-error itself (I think installations are not categorized in the product-oriented art, but rather process-oriented). There is no hierarchy between the two; rather, they are complementary. The process can give depth to the final work, while the work can visualize the questions raised during the process. Interestingly, from my viewpoint, both science and art today, established in the 20th century, have product-oriented tendencies. In both cases, it’s about delivering something complete — whether a published paper or a finished artwork — to the audience.

What is also notable is that in Asian ways of thinking, there tends to be a greater appreciation for the effort and process leading up to a goal, rather than just for “winning” at the Olympics or World Cup, for example. Unfinished processes, or those not yet reaching a goal, can themselves generate new value, especially in the form of installation experiments in both science and art. In this sense, when we talk about “mutual influence”, I believe that the idea of “incomplete completeness” in both product-oriented and process-oriented approaches could be coupled and give rise to new forms of emergence.

Is there a specific aesthetic that characterizes artistic research? Like trends or movements?

I think the aesthetics of artistic research lie in its attitudes, such as reexamining how questions are framed and embracing uncertainty. As for trends, I believe artistic research challenges the very foundation of aesthetics itself: it prompts us to ask what beauty is, whether universal beauty exists, and so on. In both science and art, within the larger environment of the universe we inhabit, the pursuit of true beauty and exploration of its methodologies is becoming increasingly relevant.

What are the problems and challenges of artistic research in an academic environment?

Some problems and challenges include the mismatch between evaluation criteria in science and art, the difficulty of “making outcomes visible,” and the gap between academic and artistic modes of expression. The open-ended, tacit nature of artistic processes often conflicts with the demand for codified, explicit knowledge in academic evaluation systems.

However, I believe that this very sense of “discrepancy” is one of the most important issues. It is precisely because this friction exists that artistic research, especially of a metaphysical nature, becomes meaningful.

What does “experimenting” mean in the case of artistic research, perhaps in contrast to the usual scientific methods?

In science, experiments emphasize reproducibility and control. In contrast, in artistic research, an experiment is an “open-ended attempt” that unfolds through unexpected discoveries, chance, and relationships with observers. Failure, deviation, and ambiguity are also essential components. Both fields involve emergence, but to exaggerate slightly, scientific experiments aim to discover phenomena and possibilities that already exist in the universe, whereas experiments in artistic research may invent phenomena and possibilities that have never existed before. They may offer answers that cannot be generated by machine learning and big data.

Do art and science have different forms of knowledge production?

Yes, unfortunately, based on the developments of the 20th century, the answer is currently yes. Science has sought universal knowledge through analysis and systematization, while art has produced individual, experiential forms of knowledge. The former values reproducibility, while the latter considers identical outcomes by different people to be banal. This again mirrors the divide between philosophy and physics. That said, while the two differ, they are fundamentally complementary forms of knowledge.

One interesting point is that artworks sometimes grasp truths that science has not yet addressed. Artists often aren’t aware they are engaging with scientifically significant perspectives. Conversely, scientists often don’t believe that artists are doing such things. Our goal, through our science-art installation experiments, is to repair and bridge this gap or missing link, reconnecting philosophy and physics into a healthy and cyclical relationship.