At the KHK c:o/re, the practice of artistic research has always been part of our research interests. For this reason, we invite fellows working closely with the arts in each fellow cohort. In the past four years, we have realized various projects in collaboration with art scholars and practitioners, and different cooperation partners, ranging from artistic positions in the form of performance, installation, discourse, and sound. Many of these events were part of the center’s transfer activities to make the research topics and interests visible, relatable, and tangible. In this sense, art can be seen as a translation for scientific topics. But the potential of the interaction between science and art doesn’t end there. Art is more than a tool for science communication, it is a research culture. Therefore, we ask the following questions: What kind of knowledge is generated in artistic production? How are these types of knowledge lived in artistic research? And, in combination with one of the central research fields of the center: To what extent are artistic approaches methodologies for what we understand as expanded science and technology studies?

To get closer to answering these questions, we talked to some of our fellows who are working closely with the arts and researching the connection between science and art. We want to find out about the epistemic value of artistic research, the methodologies and institutional boundaries of artistic research in an academic environment, and how they implement artistic research in their research areas.

In this edition of the interview series, we spoke to KHK c:o/re fellow Hannah Star Rogers.

Hannah Star Rogers

Hannah Star Rogers is a scholar, curator, and theorist of art-science. She does research on the knowledge categories of art and science using interdisciplinary Art, Science, and Technology Studies (ASTS) methods.

KHK c:o/re: What do you think is the epistemological value of artistic research?

Hannah Star Rogers: Epistemology asks: What counts as knowledge? How is knowledge produced? How do we justify what we believe to be true? Who gets to decide what is valid knowledge? These are fundamental concerns of STS, and they have been the driving force behind my interest in considering the relative power of art and science, in order to understand how these groups have persisted in knowledge production. It should be said that I have in mind the large tent of STS knowledge production, which can include things like aesthetic knowledges. Artistic research holds significant epistemological value by contributing to knowledge production in ways that are often overlooked. In my book Art, Science, and the Politics of Knowledge (2022), I try to offer a perspective on the epistemological value of artistic research. Drawing from Science and Technology Studies (STS), I argue that art and science are not distinct domains but are intertwined practices that both produce knowledge through shared methodologies such as visualization, experimentation, and inquiry.

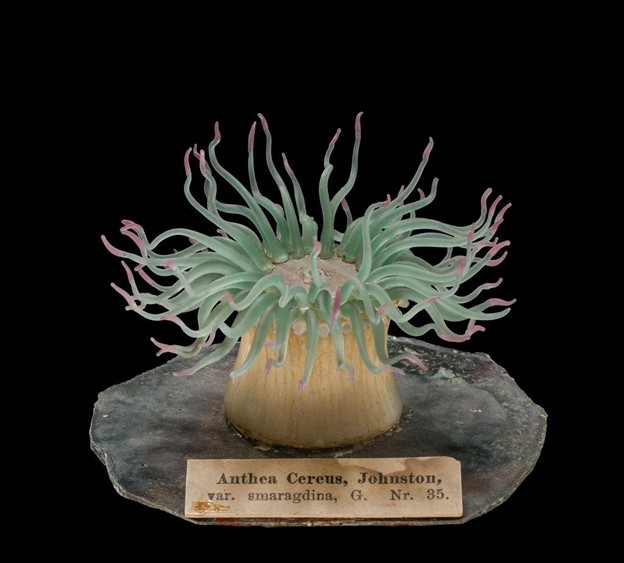

I have a particular interest in liminal objects, like the Blaschka glass marine models or Berenice Abbott’s illustrative science photographs, because they belong to both art and science networks at different times and places. Another phenomenon I’ve been interested in for what it might tell us about art and science as knowledge-making communities are intentionally hybrid art-science practices, like bioart. Their status is different but they can also help us think about STS concerns like expertise, boundary-making, and disciplinary zoning. It’s hardly news that context changes meaning, but these liminal objects are a chance to think about how people construct those meanings by invoking materials and rhetorics.

These liminal objects challenge traditional dichotomies between art and science, suggesting that these categories are socially constructed labels that order our understanding of knowledge. Building on the work of Latour and Woolgar, combined with Howard Becker, we can observe that both art and science function as networks that produce knowledge, often overlapping in their practices and outcomes. By examining the intersections of art and science and studying the works of other ASTS scholars, I observe the complex and collaborative nature of knowledge-making in art and in science. This leads me to a position of advocacy which is beyond the scope of ASTS and intersects more with my role as an art-science curator: I want to advocate for a more inclusive understanding of how an expanded understanding of what knowledge is and how it is produced, validated, and experienced.

What specific methodologies are used in artistic research? Can you give an example?

Art methods are many, but most projects involve the discovery of new processes and methods. It is easy to remark that scientists set out their methods first, but in fact, especially in the case of groundbreaking research, they often must discover the method by which to produce, reproduce, and capture data about a phenomenon. Method-making is a central part of the efforts of both artists and scientists.

Put another way, the work of artistic researchers covers many methods we are familiar with in STS, including historical and anthropological research, interviews with community members and experts, ethnographic observations, and philosophical reflections. At the same time, and I speak here about art-science, there are art processes which we tend to use less often: direct work with materials, a sensibility for offering the public an experience of the work (which often shapes choices from the beginning of artists’ processes), the duplication and hacking to standard protocols from within the sciences, and an openness to staying from our original methods. The final “product” may be an installation or performance or poetry, but often what is most revealing are the processes and decisions that shaped it. This recursive attention to method is itself a form of inquiry—and one that carries epistemological weight.

How do product-oriented art forms such as exhibitions or installations differ from process-oriented approaches to art? Is there a hierarchy? How do these approaches influence each other?

In my experience, behind the most interesting art-science projects are even more fascinating methods and processes. Showing methods and processes is a major interest of nearly all the artists (bioart, digital art, eco-arts, participatory/community arts) interviewees I have ever spoken to as part of my Art, Science, and Technology Studies (ASTS) research. It is worth noting that I particularly work with actors in art-science or art-science-technology but I believe that we would find this to be a wider pattern in other areas. A component of many contemporary artmakers’ work is to figure out how to convey their actions or the actions of others (be they communities, plants, microbes, scientists, or otherwise) through their work. Art-science curators often take up this same concern. We ask: how can we design an encounter that invites the public into the process? This can be complex, but it’s central to how we try to help audiences encounter the richness of artistic research. I’ve tried to explore some curators’ approaches to these issues in my forthcoming edited volume, What Curators Know, from Rowman & Littlefield, due out later this year. I also would argue for the need to create conditions that support open-ended artistic inquiry—akin to basic scientific research. Too often, artists are pressured to produce legible outcomes or results. But like scientists, artists should also be given space to ask difficult, speculative questions without immediate expectations of closure or utility. I have written a bit about basic artistic research (BAR) for the journal Leonardo because I believe much more needs to be done to offer artists the conditions under which they might work under the bluest skies possible, that is with open research possibilities like those that have traditionally been supported in basic scientific research.

One Comment

Comments are closed.