GIANMARCO THIERRY GIULIANA

Videogames… Today they are everywhere: they inspire books, TV series and films in the cinema, they fill sports stadiums for competitions, they are used in museums and schools, news and memes that they produce are all over our social networks, they are references in song lyrics and respective videos. Even concerts of videogame soundtracks are now common. They are in our homes and always with us on our smartphones and, last but not least, marketing and merchandising have us finding them in supermarkets as well as in souvenir shops. Their steadily growing numbers of sales are impressive,[1]https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46746593. including for the public of non-gamers, who enjoy watching videogames on YouTube, Twitch and TikTok. Undoubtedly, for at least 10 years now, they have been the most popular cultural product in many countries, in both the Global East and West. A look at data on the use of video games among children shows that their historical role will likely equal that of the book in terms of influence on the mindset of the new generations.

Gianmarco Thierry Giuliana

Gianmarco is a research fellow at the University of Turin (UniTo), Department of Philosophy and Educational Sciences within the ERC project “FACETS” and a contract lecturer for STUDIUM (UniTo). Specializing on the topic of the relationship between experience and interpretation in game-virtual realities, he has written numerous scientific articles in game studies, semiotics and philosophy journals. You can also find some of his lectures on Youtube.

Therefore, studying video games is crucial not only to better understand the present but also the future. I, an enthusiastic gamer since childhood, starting 1998, am an example of those who turned their passion into a research job. But what does it mean to study video games for a researcher working in philosophy and, more broadly, the humanities? In a nutshell, it means questioning how human beings make sense of video games, both by studying the characteristics and contents of ‘video game texts’ and the behaviour and interpretations of players. At the time when I completed my MA thesis, in 2017, I thought that this would not be very difficult, especially considering that the first studies on this topic were, back then, twenty years old. And yet five years after that thesis, as a post-doc who has continuously worked on this topic, I still find myself facing some of the problems I discovered in that early work! These ‘problems’, however, are precisely what makes the study of video games so interesting both from an academic point of view and in terms of social impact. Over the years, I have been fortunate enough to be able to present my research not only to students and university colleagues but also to game creators, family associations, teachers, psychologists and even doctors. I would thus like to let you know you about my work by mentioning the major themes of humanistic, and especially semiotic, research on digital games.

1) Storytelling & Tenth Art

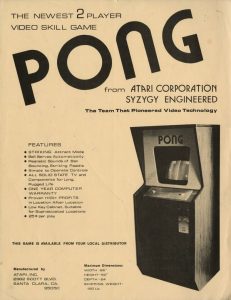

Today we are used to having video games that tell great stories with interesting characters and make us feel emotions and travel to imaginary worlds. Yet, exactly 50 years ago, video games consisted of two white sticks on a black background bouncing a square: that was Pong. What has happened in the meantime? In 1997 the important scholar Janet Murray published her book ‘Hamlet on the Holodeck'[2]Murray, J. (1998). Hamlet on the Holodeck: the Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. in which she outlined the idea that by virtue of its technical and cultural specificities, the video game could become a powerful new artistic medium of storytelling. 15 years later, we can certainly say that she was right, to the extent that today a scholar of culture cannot help but analyse the video game content as shaping our imagination. And yet, at the same time, the stories told by video games do not work in the same way as told in films or books. What kind of story is, in fact, one in which the protagonist dies after a few seconds by falling into a ravine because of his spectator? Even today there is much debate and work on how video games are a unique art form that tells stories by hybridising the languages of previous arts such as film, literature, music, and painting. A hybridisation that makes the video game a true platypus (a nickname I designated and of which I am very proud!) and challenges most previous theories and methods of analysis.[3]Aarseth E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Hence my work to create a new method of analysis capable of highlighting how a video game conveys ideas through art and storytelling.

2) The Game

Going back to Pong, there are still many video games today that do not really tell stories and are very successful: from Tetris to Candy Crush. Then, there are also all those games interested in simulating realities rather than fiction: from realistic sports games to Microsoft Flight Simulator. To these, I also add all those games in which the real ‘story’ is, as in sport, that of the splendid performance of their players: from historical fighting games like Street Fighter to MOBAs (Multiplayer Online Battle Arenas) like League of Legends to Fortnite or Among Us. These games without great artistic or narrative pretensions are often the subject of harsh and often unfair criticism. I find that, quite on the contrary, it is precisely on the basis of such games that a part of the academia reflected and still works on that cultural form which has been, so to speak, ‘removed’ from the history of arts and culture: games! Not only has the game, in fact, existed since 2500 B.C. but, as Johan Huizinga writes in his valuable ‘Homo Ludens’, it has always been at the heart of human societies and is a model for thinking and rethinking reality.[4]Huizinga, J. (1985 [1938]). Homo Ludens: Proeve Ener Bepaling Van Het Spelelement Der Cultuur. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Original Dutch edition. All of the most fundamental categories of language and human thought are in fact called into playing and games: they construct both a subjectivity, a destiny, a temporality and a world of reference. In the humanities, however, scholars interested in play are still a minority as the dominant theoretical models come from studies on narration. A negative stereotype of play as mere ‘entertainment’ still lingers. Thus, an important task in my work consists in trying to remind the academic community that nothing is more serious than playing!

3) Participatory Culture

Whether it is creating and being a detective engaged in solving a case in the world of Disco Elysium or beating up your opponent as much as possible in the latest Dragon Ball Fighter Z, in all cases, video games require players to participate in a committed way. Although academics such as Umberto Eco demonstrated back in the 1980s that the reader and spectator are never ‘passive’, video games certainly give those who play them greater manipulative power over the meaning of the text than previous media do. This critical and creative manipulation of mass culture by its consumers is a major theme in the humanities and social sciences A leading figure here is Henry Jenkins.[5]Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: media education for the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Trad. it. Jenkins, H. (2010). Culture partecipative e … Continue reading If, however, in the case of films or books this occurs a posteriori, in the case of video games it occurs in fieri (i.e., ‘in the happening’) and sometimes even a posteriori with the possibility of directly modifying the game files. As such, studying video games also means studying the interpretations, rewritings and creations of their players. For a long time, the study of these ‘personal interpretations’ was avoided by disciplines such as game studies. This was epistemologically justified. Nowadays, however, thanks to platforms such as YouTube or Twitch, these interpretations are themselves presented as analysable texts. My work is in this sense also one of research and collection of materials that constitute a history of interpretations of digital worlds.

4) Virtual Reality & Digital Technology

A video game is first and foremost software, which makes video games of great interest for studying the processes and outcomes of interactions between humans and digital technology. Algorithms and artificial intelligence are topics of great importance for contemporary societies and have been part of video games since their birth. It is precisely the ‘algorithmic core’, as the very important video game scholar Ian Bogost puts it, that makes videogames and their narratives very different from all other games.[6]Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Moreover, for at least twenty years video games have been ‘virtual realities’ where people get married, manifest, find friends, trade, hold funerals and much more. Studying video games is thus also equivalent to studying the way social reality and human relationships are changing through technology. In my particular case, the aspect of computer technology that I study most closely is the role of digital faces in virtual realities. A trully fascinating topic!

5) Learning

In 2005, the scholar James Paul Gee published an important article in which video games were described as ‘learning machines’.[7]Gee, J. P. (2005). Learning by Design: Good Video Games as Learning Machines. In E-Learning and Digital Media, 2(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.1.5. Videogames, in fact, almost always involve a great deal of physical and cognitive effort in order to improve one’s performance so that one can win. This learning process has to do with the development of certain perceptual and motor skills, but it also has a lot to do with the rules and content of the game. Those who play a car racing simulator like Gran Turismo develop not only reflexes, but a very deep knowledge of how cars work.[8]https://www.gamespot.com/articles/meet-the-gran-turismo-player-now-driving-race-cars-for-real/1100-6419397/. Similarly, someone who plays a strategy game like Total War will learn a lot about characters, objects, practices and historical events. Even those who play the fictional game Assassin’s Creed 2 will learn a lot about the city of Florence in the 15th and early 16th century and will still be able to find their way around the city today almost as if they had already been there![9] https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/v5c42/how_close_were_the_cities_of_assassins_creed_2_to/. In ‘author’ games, this learning even becomes emotional and often involves asking players to make difficult choices that are of great ethical relevance. For teachers there is therefore a great deal of interest in the video game medium from the point of view of both its generic learning potential and its educational potential. Finally, this very strong connection between physical action and what is represented on the screen has prompted an unprecedented collaboration between the humanities, philosophy and cognitive sciences. So, if you were to burst into a researcher’s bedroom and see them dancing wildly in VR in Beat Saber, don’t judge them: they are probably working on bringing together classical theories of thought with theories of embodiment!

There are many other interesting aspects to mention but I end this post on this note. I hope I have given you a little insight into my work as a video game semiotician and, above all, to have convinced you (at least a in part) of the importance of videogame studies.[10]In case you would like to read more: http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/quilting-the-meaning-gameplay-as-catalyst-of-signification-and-why-to-co-op-in-game-studies/. The importance of videogame research is due not only to the theoretical and social impact of videogames but also to their requiring of a tight collaboration between all those who study and produce them.

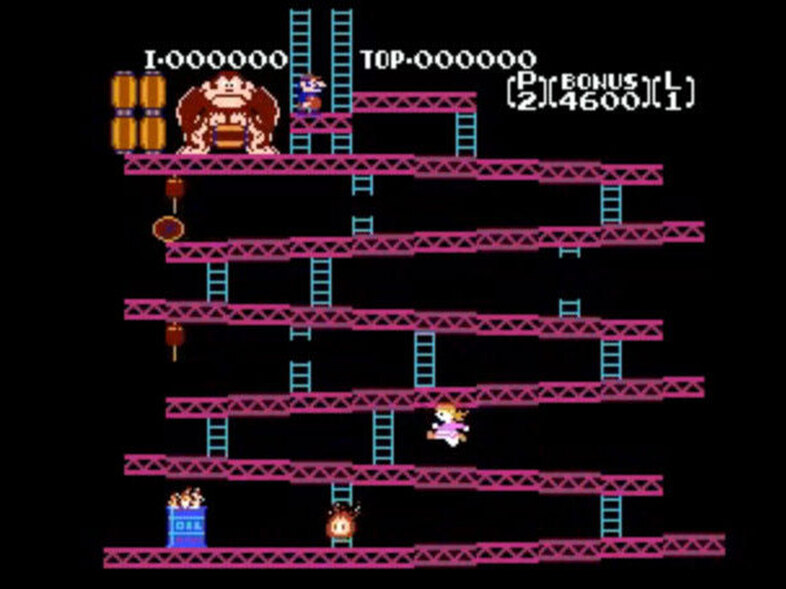

Featured image: 2013 hack of Donkey Kong, 1981. More info at: https://www.wired.com/2013/03/donkey-kong-pauline-hack/.

Proposed citation: Giuliana, Gianmarco. (2022). Studying Videogames: A 20-Year-Old Challenge for the Humanities. https://khk.rwth-aachen.de/2022/12/24/5266/5266/.

References

| ↑1 | https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-46746593. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Murray, J. (1998). Hamlet on the Holodeck: the Future of Narrative in Cyberspace, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. |

| ↑3 | Aarseth E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. |

| ↑4 | Huizinga, J. (1985 [1938]). Homo Ludens: Proeve Ener Bepaling Van Het Spelelement Der Cultuur. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff. Original Dutch edition. |

| ↑5 | Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: media education for the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Trad. it. Jenkins, H. (2010). Culture partecipative e competenze digitali: media education per il 21. Secolo. Milano: Guerini studio). |

| ↑6 | Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. |

| ↑7 | Gee, J. P. (2005). Learning by Design: Good Video Games as Learning Machines. In E-Learning and Digital Media, 2(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.2005.2.1.5. |

| ↑8 | https://www.gamespot.com/articles/meet-the-gran-turismo-player-now-driving-race-cars-for-real/1100-6419397/. |

| ↑9 | https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/v5c42/how_close_were_the_cities_of_assassins_creed_2_to/. |

| ↑10 | In case you would like to read more: http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/quilting-the-meaning-gameplay-as-catalyst-of-signification-and-why-to-co-op-in-game-studies/. |