At the KHK c:o/re, the practice of artistic research has always been part of our research interests. For this reason, we invite fellows working closely with the arts in each fellow cohort. In the past four years, we have realized various projects in collaboration with art scholars and practitioners, and different cooperation partners, ranging from artistic positions in the form of performance, installation, discourse, and sound. Many of these events were part of the center’s transfer activities to make the research topics and interests visible, relatable, and tangible. In this sense, art can be seen as a translation for scientific topics. But the potential of the interaction between science and art doesn’t end there. Art is more than a tool for science communication, it is a research culture. Therefore, we ask the following questions: What kind of knowledge is generated in artistic production? How are these types of knowledge lived in artistic research? And, in combination with one of the central research fields of the center: To what extent are artistic approaches methodologies for what we understand as expanded science and technology studies?

To get closer to answering these questions, we talked to some of our fellows who are working closely with the arts and researching the connection between science and art. We want to find out about the epistemic value of artistic research, the methodologies and institutional boundaries of artistic research in an academic environment, and how they implement artistic research in their research areas.

In this first edition of the interview series, we spoke to KHK c:o/re alumni fellow Nathalia Lavigne.

Nathalia Lavigne

Nathalia Lavigne [she/her] works as an art researcher, writer and curator. Her research interests involve topics such as social documentation and circulation of images on social networks, cultural criticism, museum and media studies and art and technology.

KHK c:o/re: What do you think is the epistemological value of artistic research?

Nathalia Lavigne: Artistic research and research-based art have become huge topics in the last two decades and some art historians have even suggested that there is an overabundance of these terms in contemporary art exhibitions in recent years. However, there are several epistemological values coming out of this approach. In general, it comes from combining knowledge from different fields, making them more visible outside of academia (in cultural spaces), and eventually contributing back to the respective field. This interconnectivity of knowledge can be valuable to academia by bringing new perspectives on objectivity and methodologies and providing more space for speculation and a more enjoyable way to absorb research.

What specific methodologies are used in artistic research? Can you give an example?

I can talk about some methodologies developed by artists I have worked with, either as a curator or when writing about their work. One example is the project (De)composite Collections, developed by Giselle Beiguelman, Bruno Moreschi, and Bernardo Fontes for the ZKM’s intelligent.museum residency in 2020. They analyzed the collections of two Brazilian museums through AI reading systems. Using these datasets, which were algorithmically processed with GANs (Generative adversarial networks), they questioned what other art histories might emerge from AI’s readings of the images and how these systems could contribute to understanding the gaze as a historical construct. Part of this methodology involved the development of a dataset organized by recurrent themes in Brazilian modernism, such as indigenous people, people of color, white people, and tropical nature. This work was also part of a project developed by students and faculty members at the University of São Paulo (USP), so it originated in an academic environment.

Is there a specific aesthetic that characterizes artistic research? Like trends or movements?

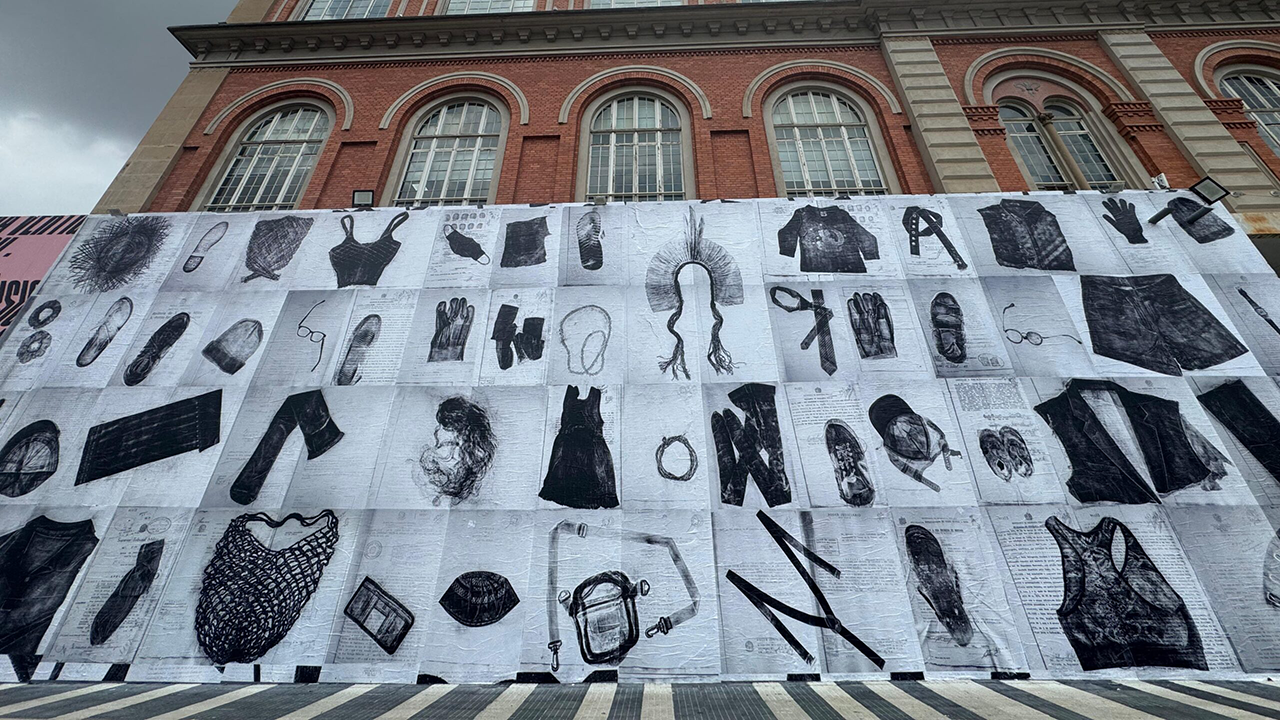

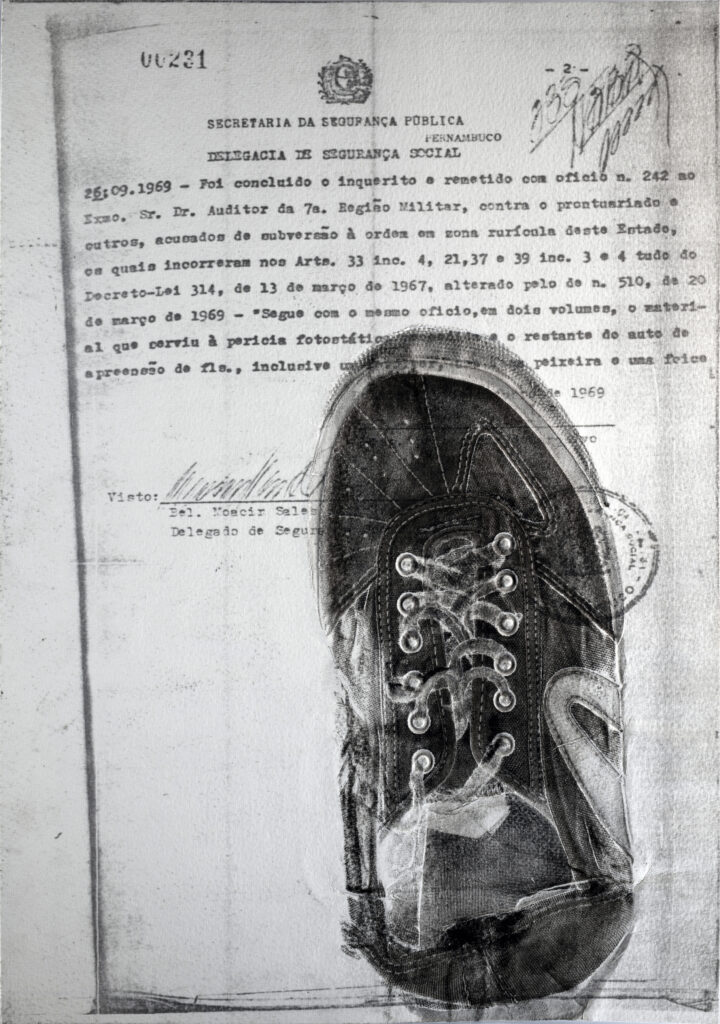

I would say that there are some characteristics that we can notice in the way these projects are formalized depending on the period. One that has been quite evident in recent years is the so-called “forensic aesthetics.” Popularized by artist and researcher Eyal Weizman, the term refers to a methodology used in art to explore the memory of places and objects as forms of testimony. This aesthetic has influenced artists working on topics such as repressed memory and collective amnesia in different contexts. One artist I have collaborated with as a curator is Rafael Pagatini, whose work addresses the memory of the Brazilian Civil-Military Dictatorship (1964-1985) in the present. In his process, he applies methodologies from both history and law, which affects how these memories are addressed (or omitted) from institutional archives.

But there are also artists who have been collaborating with scientists long before this kind of artistic production was labeled “artistic research.” For example, since the 1990s, Eduardo Kac has developed projects with bioengineers, geneticists, and, more recently, astronauts and space agencies to create his space arts projects. In his case, the methodologies and the process of materialization vary greatly depending on each project.

What are the problems and challenges of artistic research in an academic environment?

In general, the challenges in an academic environment are that practice-led research in the arts is still not fully recognized as eligible for funding or career assessment procedures. But this has been changing, especially since the Vienna Declaration on Artistic Research co-written by different European associations in 2020. However, in countries from the Global South — or even in the US, where public funding for research is limited — this reality is very different. As I’ve heard from artists engaged in artistic research in Brazil, for example, the challenges are not so much in an academic environment but rather in the art system in general. As the Brazilian art system still largely revolves around the market due to the fragility of public institutions, research-based art finds it difficult to fit into a more commercial logic that prioritizes art objects that are less process-oriented.