RUTH LORAND

Aryeh Ludwig Strauss (1892–1953) was a German-Hebrew Poet, literary critic and researcher. He was born in Aachen, fought in WWI, worked as a dramaturg in Düsseldorf, studied in Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität, Frankfurt am Main, and habilitated in Aachen with a study of Hölderlin’s Hyperion (1929). He taught in Aachen as Privatdozent. In April 1933 the ministry of science, art and education in Berlin ordered the rector of the University of Aachen, to dismiss all Jewish professors including Dr. Strauss.

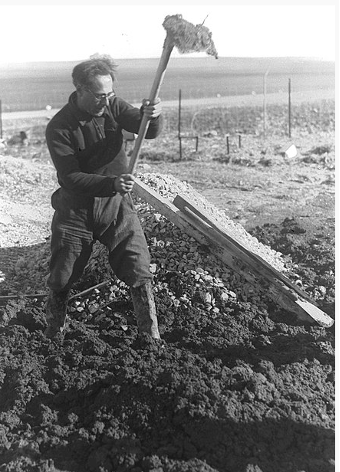

The Strauss family, Ludwig, his wife Eva (Martin Buber’s daughter), and their boys, Immanuel and Michael, lived in Weberstr. 31, Aachen, until Ludwig’s position was terminated. The family left Germany (1935) and immigrated to Palestine, which later became the state of Israel (1948). Ludwig joined Kibbutz Hazorea in which he worked in the fields and made his first steps as a Hebrew poet.

Ruth Lorand

Ruth Lorand is professor emeritus of philosophy and aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy at the University of Haifa. She is an expert in the philosophy of concept forming. Her magnus opus Aesthetic Order. A Philosophy of Order, Beauty and Art was published in 2000 at Routledge after a decade of thorough writing and rewriting. In the preface to this monograph she confessed that Prof. Michael Strauss had inspired her to focus on aesthetic order, “an unpredictable, lawless order”, she said. In other words, a difficult subject worth a decade of exploration to turn into a comprehensive theory.

Prof. Ruth Lorand visited the Käte Hamburger Kolleg “Cultures of Research” in March and April 2023 together with her husband Prof. Giora Hon, professor emeritus of philosophy of science and epistemology at the Department of Philosophy at the University of Haifa. We are very grateful for her visit, her contributions and her blog article about Aryeh Ludwig Strauss, and we hope she will return to Aachen next year for a workshop on concept formation.

Find more information at Ruth Lorand’s academic website.

Later, the family moved to the youth village Ben Shemen where Ludwig taught literature for two years. Jerusalem became afterwards their permanent home and there, at the Hebrew University, A. L. Strauss was among the founders of the Comparative Literary Department. He served as a chair until he got ill; he was replaced by another celebrated Hebrew poet, Leah Goldberg.

My first encounter with the literary work of A. L. Strauss was about 17 years after his passing at the age of 60. In my first year as a student of Hebrew Literature at the University of Haifa I found his name in the required reading list: Studies in Literature by A. L. Straus. It was a most inspiring collection of essays in which I read for the first time a literary analysis of some chapters in Psalm, side by side with an analysis of Goethe’s Faust and Racine’s Phèdre. The introduction to these essays revealed the sad fact, that it was edited and published after the death of the author. The editor was his close friend and a Hebrew poet of German origin as well, Tuvia Rübner, who also edited (together with Hans Otto Horch) Strauss’ Gesammelte Werke (four volumes) and translated to Hebrew some of his poems. Although this was a required reading, it was gratifying due to its clarity and the enlightening observations it offered. In many ways it was an eye opener. From there I went on to reading his Hebrew poems which were not close in content to my world as a young Israeli, but their melody and rhythm reminded me of some Psalm chapters I knew by heart.

It was in my second year at the university, when I took Philosophy as a second subject, that I found another connection to A. L. Strauss. My most beloved and influential philosophy teacher was, as I found out later, the son of the author of my first year compulsory reading. Michael Strauss, whom everybody called Micha, was born in Aachen (1931) and immigrated to Israel with his parents and older brother, Immanuel. Micha was admired by the students who packed his classes on “Modern Philosophy: from Descartes to Kant” and his seminars, “Spinoza’s Ethics”, “Theories of Values”, and a few more. When I began my academic career as a Teaching Assistant in the same Philosophy Department, Micha became my friend and colleague, although it took me a while to address him as Micha and not as Dr. Strauss. We had long and inspiring conversations on literature and philosophy. He hardly mentioned that his father was a known poet and scholar in Germany nor did he ever refer to the fact that the family had been forced to leave Aachen. That Micha was the grandson of the renowned scholar, Martin Buber, was not an issue to be discussed, as the grandson’s philosophical interest was much different from that of his grandfather. However, Micha’s interest in poetry and literary prose was clearly inspired by his father; celebrated poets and philosophers of that time in Israel, were friends of Micha’s family.

Micha was 22 when he lost his father, and it was quite clear that his soul longed for him and that the connection between them was more than a father-son relation. Micha admired poets and his father among them, but never attempted to write poetry himself. He was a philosopher of the old school, much influenced by the German tradition, who did not publish enough by academic standard, but was endlessly occupied with philosophical issues. His study’s walls were covered with notes written on small pieces of paper. Did he follow his father with this mode of reflection? I don’t know. In the introduction to A. L. Strauss’ collection of papers the editor, Rivner, wrote that the author left mostly scattered drafts, notes, and only a few completed papers. For both, father and son, so it seems, the very act of thinking, reflecting and forming ideas was more important than having them in print. Both father and son were praised as unique and inspiring teachers. I have no first-hand experience with the father’s teaching, but I know that the son, Micha, was my best philosophy teacher and is still today a source of inspiration. By now, both are gone.

In my recent sojourn in Aachen, the birth place of Strauss the poet and Strauss the philosopher, I was curious about their lives in the early 1930s. With the kind and efficient help of the RWTH Archive’s team I found documents related to A. L. Strauss. I was particularly amazed to read a detailed exchange between the ministry of science, art and education in Berlin and the Rector of the Technische Hochschule in Aachen concerning the immediate dismissal of all listed Jewish teachers. A letter sent by the student organization (ASTA) to Berlin declared that German Literature should not be trusted in the hands of teachers who are not of a genuine German origin. Such teachers, so the letter goes, may implant in the students a non-German spirit.

Walking the streets of Aachen in the vicinity of Weberstr. 31, I wondered about the flimsy turns of history. I was thinking about what good literature and philosophy do; how my own life was so deeply influenced by these two Strauss from Aachen.

References

Strauß, Ludwig. 2002. Gesammelte Werke. In 4 Volumes. Eds. Tuvia Rübner and Hans Otto Horch. Göttingen: Wallstein. (Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung Darmstadt. 73) ISBN 3-89244-198-7

One Comment on “On Aryeh Ludwig Strauss: a German-Hebrew poet from Aachen”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback: c:o/re Highlights of 2023: A look back