Book launch: The world’s first full press freedom

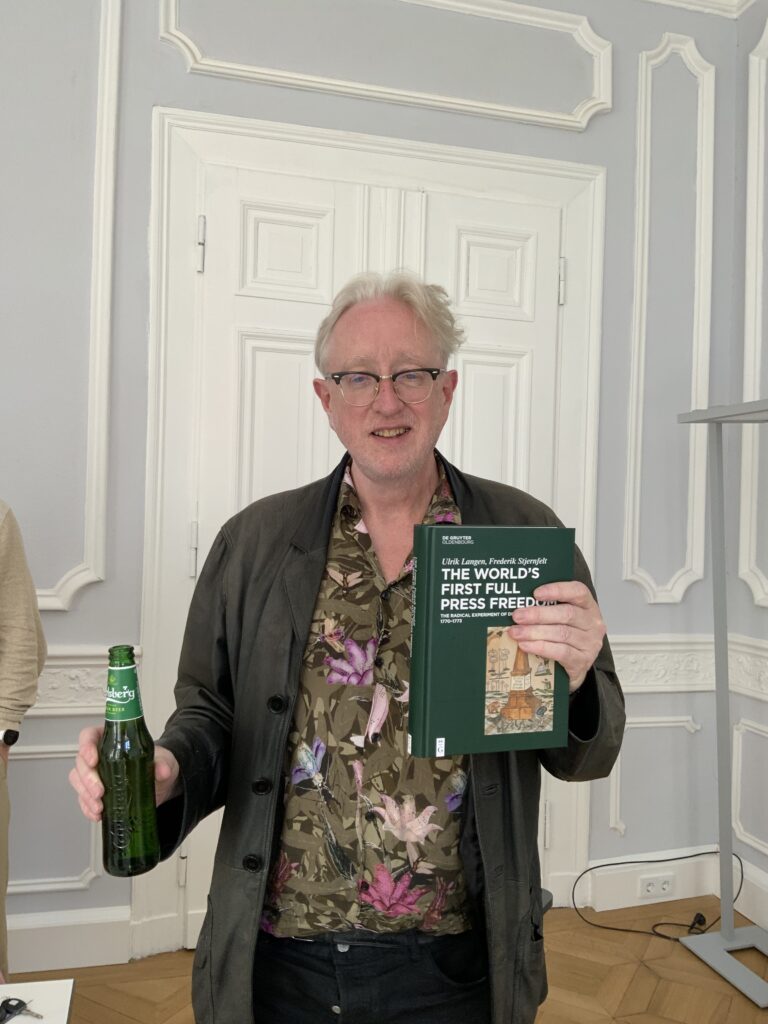

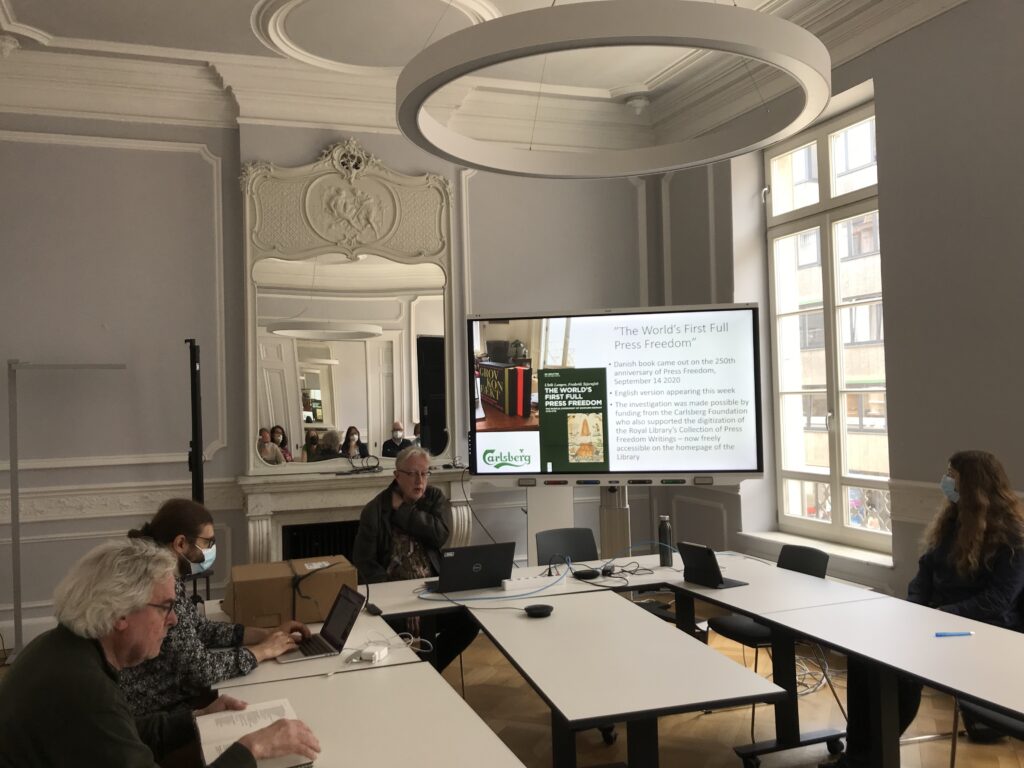

We had a book launch at c:o/re, as Ulrik Langen and Frederik Stjernfelt‘s book The World’s First Full Press Freedom: The Radical Experiment of Denmark-Norway 1770-1773 is being published this week. Frederik Stjernfelt gave a thorough presentation of the book on 25.05.2022. This was a particularly appropriate date for a discussion on press freedom as, on the same day, in Aachen, there took place the ceremony of conferring the International Charlemagne Prize to the leading Belarusian political activists Maria Kalesnikava, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Veronica Tsepkalo, who lead the fight for democracy in Belarus.

This is an adaptation for international audiences of their previous book written in Danish, also together with Henrik Horstbøll, comprising two volumes, Grov Konfækt. Tre vilde år med trykkefrihed, 1770-73. To address an international audience, Ulrik Lange and Frederik Stjernfelt both reduced the size of the initial text and, also, approached some new topics, to do with the international reactions to the episode of the history of Denmark-Norway (The Oldenburg Monarchy) that the book discusses.

The book offers a historical investigation of the interesting episode in the history of Denmark-Norway when Press Freedom was introduced by the German Radical Enlightener J.F. Struensee, who was hired in 1768 to take care of the mental health of King Christian VII. Struensee became the King’s favourite and achieved political power, backed also by a small group of reform-oriented top officers. This allowed Struensee, for a brief 16-months period, to effectively be dictator of Denmark-Norway and, as such, to introduce close to 2000 pieces of new legislation, many of them with Radical Enlightenment inspirations.

In this context, the book zooms in on the implications of and reactions to the law of 14 September 1770 that stated that censorship is abolished in order to facilitate the ”Impartial Investigation of Truth”, to go against ”Fallacies and Prejudices of earlier Times”, and to ”attack Abuse and reveal Prejudices”. This was an Enlightenment ideal. Struensee could not have foreseen, probably, the many types of social implications of absolute press freedom. He was, eventually, ousted and executed by coup-makers in the middle of the Press Freedom period.

Showing simultaneously how press freedom is crucial for democracy and human rights and how it is also dangerous, the exploration of this historically first case of full press freedom is highly relevant for contemporary debates on freedom of expression online and post-truth attitudes. The detailed investigation that the book offers relies on an impressive categorisation of about 1000 pamphlets published during this press freedom period.

As the first book on the matter, in Danish, covers in great detail the events in Denmark-Norway of this historical episode, the new English adaptation also compares the Copenhagen pamphlet storm of 1770 with the pamphlet storms that took place in Vienna in 1781 and in Paris in 1788.

The authors explain that, in all three cases, Enlighteners introducing Press Freedom were disappointed with the result. The population hardly became more moral and enlightened, but rather used freedom to split into warring factions, to print and buy cheap entertainment, libel and obscenities. Also, in all three cases, an immediate explosion of prints waned over a number of years, finally to be restricted again by different means, such as post-print censorship, prohibition of anonymity, signal cases, taxation, licensing requirements, among others. However, very importantly, all three cases made clear the modern consequences of Press Freedom as it would spread in Western democratic constitutions through the 19th Century.

The book draws many relevant conclusions on freedom of speech in general. As particularly relevant for contemporary issues, the book argues that press freedom is not natural, nor automatic. There is always a pretext to curtail it, and every government may find reasons to do so.

Press freedom is unpredictable and cna involve many types of of drawbacks, such as libel, threats, calls for sedition, fake news. To this day, (full) press freedom is contested: there is no agreement about its limits. Press freedom creates a public sphere, drawing people to consider political options and to conceive themselves as political subjects.

Summarising, the book highlights the importance of accepting conflict as part and parcel of the democratic process and the pursuit of human rights. Press freedom is instrumental in this regard, as it connects to a conflictual view of society: there are and always will be different social strata, different political positions, different interest groups, different power centers and their conflict is better waged in the open.