As part of the interdisciplinary workshop “After Networks: Reframing Scale, Reimagining Connections”, which will take place at the SuperC of RWTH Aachen University on April 16 and 17, 2025, media scholar Lori Emerson will come to Aachen and give a keynote speech about her new book “Other Networks: A Radical Technology Sourcebook” (Anthology Editions, 2025). We asked her a few questions in advance to get a better understanding of how she thinks about and works with networks.

Lori Emerson

Lori Emerson is an Associate Professor of Media Studies and Associate Chair of Graduate Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. She is also the Founding Director of the Media Archaeology Lab. Find out more on her website.

In your new book Other Networks: A Radical Technology Sourcebook, you present networks that existed before or outside of the internet, digital as well as analog. What would you say do all of these different models of networks have in common?

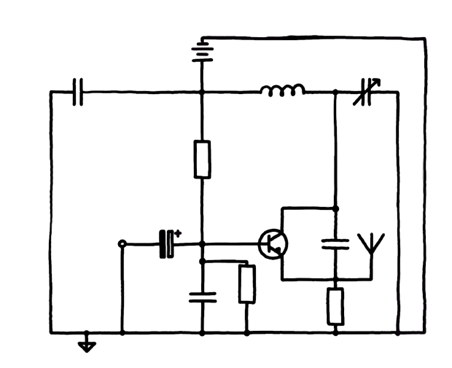

Many of the networks in Other Networks began as small experiments by a few individuals that didn’t necessarily have aspirations to make sure these networks had a global reach, or that these networks could not be replicated by other individuals, or that they would overtake every other kind of communication at a distance. More, because of their relative simplicity, most of these networks can be recreated today for small groups of people. My hope is that, along with my colleague Dr. libi striegl who is the Managing Director of the Media Archaeology Lab (the lab I direct and that has supported a lot of the research behind Other Networks), we will continue to create “recipes” for building small “other networks.” We have already published a small pamphlet called Build Your Own Mini FM Transmitter that very clearly and carefully walks people who have no background at all in electronics through the process of making what’s basically a micro-broadcasting station.

Do you have a favorite network example?

I am fond of all the networks in Other Networks! But one particular network I like to talk about is an example of an imaginary network: the pasilalinic-sympathetic compass, also referred to as ‘snail telegraph.’ This network was created by French occultist Jacques-Toussaint Benoît to demonstrate that snails are capable of instantaneously and wirelessly transmitting messages to each other across any distance. Benoît’s theory was that in the course of mating snails exchange so-called “sympathetic fluids” which creates a lifelong telepathic bond which also enables them to communicate with each other. He believed he could induce snails to transmit messages faster and more reliably than by wired telegraph by placing a snail on top of a letter and then, with the prodding of an electric charge, the snail would transmit the letter to another snail placed at some distance. The pasilalinic-sympathetic compass itself consisted of twenty-four different wooden structures containing a zinc bowl, cloth that had been soaked in copper sulphate, and a snail glued to the bottom of the bowl. Benoît unsuccessfully demonstrated the snail telegraph to a journalist from La Presse, Jules Allix, in October 1850.

What is the materiality of a network? In your new book, you separated them into four categories: Wireless, Wired, Hybrid and Imaginary. How was the process of organizing the networks into these different categories? Do you think it helps to visualize how a network can be materialized?

Creating a taxonomy for organizing these other networks was the most challenging part of writing Other Networks and, like any taxonomy, the system I settled on is still far from perfect. It took me many months to come up with a system for organizing networks according to their underlying infrastructure and that didn’t simply replicate historiographic conventions of accounting for technological inventions chronologically or by inventor. In other words, I wanted to underscore that networks emerge, disappear, and re-emerge slightly configured or re-combined over and over again; they also are rarely the work of a single person. More, accounting for networks in terms of chronology or “inventor” usually distracts us from seeing networks as material. Today, despite all the excellent work that has been done to reveal the material underpinnings of the internet (from its undersea cables to cable landing stations etc.), still the vast majority of people don’t know where the internet is, how it works, or where it came from. It might as well be immaterial! By contrast, I wanted to make it clear in Other Networks how, for example, there’s radio in the internet; that radio is part of the electromagnetic spectrum; that, even though we can’t see it, the electromagnetic spectrum is a ubiquitous natural resource; and that we as individuals and as communities can learn how to access this natural resource. Perhaps it’s old fashioned to say so, but I still believe that understanding the materiality of networks and how they work empowers us to build our own networks.

Where do you see the future of networks? In the digital or analog space?

One thing that became clear to me in the course of doing research for Other Networks is that there really isn’t a clear distinction between the analog and the digital like I was taught in graduate school. Telegraph communications that use, for example, morse code and that are transmitted over telegraph or telephone wires are digital in the sense that they are pulses of electricity in much the same way that digital computers use pulses of electricity to indicate 1’s and 0’s. In this sense, I think the future of networks is less about whether they’re analog or digital and more about whether they are built for small, local communities; whether they are cooperatively owned rather than corporate-owned; whether they can be maintained over the long run without resorting to blackboxing; and, finally, whether they have built-in structures to resist surveillance, tracking, and monetization.

Thank you so much for the interview, Lori!

More information about the workshop, the program and registration can be found on this website.

Header photo: Jenna Maurice