RENÉ VON SCHOMBERG AND ANDONI IBARRA

Responsible Research and lnnovation (RRI) has become increasingly important since it was introduced as a cross cutting issue under the European Union (EU) Framework Programme for Research and Innovation “Horizon 2020” (2014-2020). Subsequently, it became an operational objective of the strategic plan for “Horizon Europe (2021-2027)”, the new EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation. ln EU member states, there are also various initiatives supporting RRI, notably under schemes of national research councils (the United Kingdom, Norway, and the Netherlands, among others). The concept also resonated outside the EU, notably in the United States, and in China it became part of the national five-year plan for Science, Technology and Innovation.

However, there are a variety of approaches as for how it should be implemented. Scholars provide a variety of perspectives and assessments of what RRI need to address. However, all scholars generally share the notion that RRI requires a form of governance that will direct or re-direct innovation towards socially desirable outcomes. This initial definition that Von Schomberg provided in 2011 captures the commonalities of the field:

Responsible Research and Innovation is a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society).

This definition was not proposed as an end-result but as a starting point for an ever-growing field of research and innovation actions. The definition was put forward, first, to highlight that dominant public policies only negatively select science and technology-related options, notably by the management of their risks. According to the still dominant ideology, all innovation will contribute to common prosperity regardless of its nature. The notion of responsible research and innovation makes a radical break with such an ideology. Furthermore, this ideology tells us that innovations cannot be managed or be given a particular direction. Also on this front, the notion of responsible innovation breaks with this ideology and puts the power for a socially desirable change through innovations into the hands of stakeholders and engaged citizens. However, these stakeholders have to become, or be incentivized or even enforced to become, mutually responsive to each other in terms of social commitments to such change.

René von Schomberg

René is Guest Professor at the Technical University of Darmstadt, Germany. He was a European Union Fellow and Guest-Professor at George Mason University, USA, from 2007 to 2008 and has been with the European Commission from 1998 to January 2022. In his research project as a senior fellow at c:o/re, he focusses on the values of “openness” and “responsibility” in science policy.

Andoni Ibarra

Andoni is Professor of Philosophy of Science at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). He is also the Principal Investigator of PRAXIS Research Group, the founder of the Miguel Sánchez-Mazas Chair. As a senior researcher at c:o/re, he is developing an anticipatory governance framework aimed at assessing and guiding the implementation of responsible anticipatory practices in research and innovation in the field of nanotechnologies.

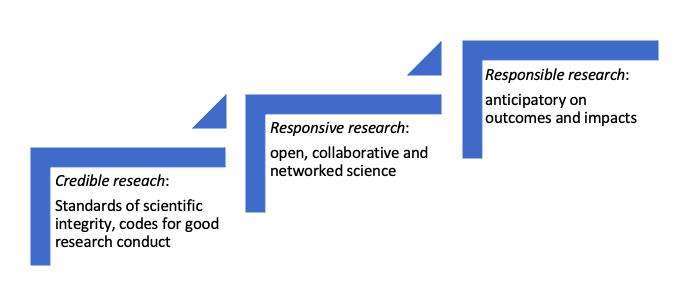

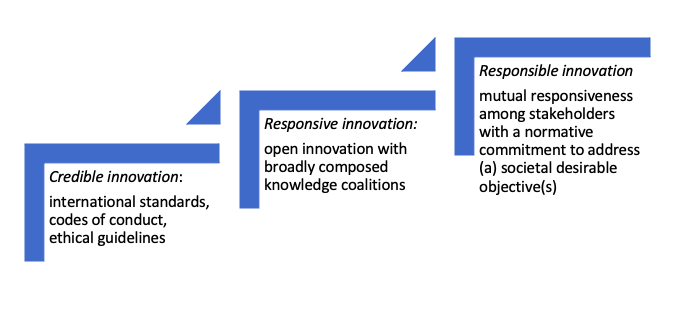

Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) imposes normative requirements on research and innovation processes resembling three successive steps of an incremental higher ambition with distinct features. The distinct features reflect the normative requirements of firstly, credible research (through among others ‘codes of conduct’ and standards for scientific integrity), secondly responsive research (by opening up science to societal demands), and finally responsible research (which includes the anticipation on socially desirable outcomes) for the research dimension. Equally distinct features reflect the requirements of credible innovation, responsive innovation, and responsible innovation (Von Schomberg, 2019).

For each of these steps, a framework for good practice is needed. The contributions to the workshop “Open Scholarship, Responsible Innovation and Anticipatory Governance” that took place on June 29-30, 2022, at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg: Cultures of Research, can be seen as attempts to contribute to these good practices for a single step or for multiple steps. First, the creation of knowledge in science underlies distinct universalizable codes for ‘good’ research conduct, enabling a global research practice that is virtually independent of cultural and national constraints. As the previous director of the US National Science Foundation Subra Suresh put it: ‘Good science anywhere is good for science everywhere’. The issue of ‘what is good science?’ can be seen as purely internal matter of the scientific community. Indeed, it has always been scholarly societies or academies of science who have tackled this issue of credible research, which arguably also constitutes the most basic requirement of RRI.

However, we should not forget these scholarly societies and other scientific institutions only engaged with the internal issue of good scientific conduct and scientific integrity because of external societal pressure and clear ethical challenges. That this is an issue which is far from settled.

Yet, Responsible Research and Innovation with within its dimension of ‘open scholarship’ has put additional pressure on revising or extending the normative requirements of this first step for RRI governance, namely credible research and thereby calling for revision of existing codes of conduct for good science particular with a view on achieving credible, reproduceable and re-usable data, all necessary to enhance science as such.

Open research and scholarship can be defined as ‘sharing knowledge and data as early as possible with all relevant knowledge actors‘ (Von Schomberg, 2019). Open research and scholarship (in the research policy-making context often simply referred to as ‘open science’) is operationalised by researchers who use, re-use and produce open research outputs such publications, software and data and who engage in open collaboration with other scientists, as well as seek, whenever appropriate for the subject matter of study, open collaboration with knowledge actors external to science such as industrial organisations, civil society organisations or public authorities.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a change in the modus operandi of doing science as public authorities started to incentivize open science globally. This made it possible to deliver swiftly on vaccines. Without open science, the market introduction of these vaccines would have taken, under the usual circumstances of competitive and too closed forms of science, minimally a decade.

The research value ‘openness’ can be seen as a constitutional value for the scientific community as such. Open scientific discourse, the exchange of ideas and competing approaches is fundamental for the progress of modern science. ‘Openness’ is presupposed by the Mertonian norm ‘Communism’ (common ownership of scientific discoveries) and thus part of the ethos of science (Merton, 1942). However, the meaning of ‘openness’ is manifold and is dependent on the scientific discipline or the scientific mission in which it is embedded. With the emergence of Open Science, equally ethical issues concerning the limits to ‘openness’ in particular contexts become evident, such as the employment of sensitive data in security or biomedical fields.

Open research and scholarship manifest itself notably in the case of interdisciplinary scientific cooperation with a view on developing a socially desirable output as the case of Covid-19 demonstrated. Open research and scholarship have been incentivized with a view of making science more efficient (better sharing of resources), more reliable (better verification of research data) and making it more productive with a view on a socially desirable output (in this case a vaccine). Research virtues or norms have been phrased historically as a subset of general human virtues. From the Mertonian CUDOS norms (Merton,1942) to the codified principles of research integrity incorporated in the All European Academies’ European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, norms or principles have been described as a fundament of a ‘good’ research practice. The ‘responsibility’ of the scientific community is then often described as an overarching duty to promote, manage, and monitor a research culture that is based on the scientific integrity of its members (ALLEA, 2017). Furthermore, research integrity does include a particular form of responsibility, namely the accountability for the whole internal process of science from idea to publication. The ‘implementation’ of scientific integrity is managed by self-regulation of the scientific community.

Traditionally the scientific community has stopped short of taking any form of responsibility for consequences and side-consequences of the societal use of scientific insights and technologies and its unpredictable societal impacts. The responsibility for those consequences has been ‘allocated’ to the political system. This division of responsibilities has become subject of intense debate, virtually since the whole period after Word War II. Intense debate on the risks of emerging technologies have led to the adoption of national laws and European directives on the risks, the quality and efficacy of products arising from the use of new technologies. Western societies have gained the capacity to indirectly govern emerging technologies, notably through its risk management and to outlaw specific undesirable outcomes, such as cloning human beings. Our institutions have thus governance structures in place to manage the risks of technologies such as nuclear technology, genetic or nanoengineering. However, we do not have established capacities to anticipate or direct science and innovation towards socially desirable outcomes such as vaccines or outcomes that underpin or make the transition towards sustainability possible. Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) has emerged as response to this deficit in the governance of science and technology. RRI requires a form of governance that will either direct science towards socially desirable outcomes or manage innovation processes in such a way that those socially desirable outcomes are more likely to emerge (Von Schomberg 2019).

It is therefore desirable to develop further a governance framework which institutionalizes the organization of co-responsibility across the spheres of science, policy and society on a subject matter which require open science missions such as Covid-19. The institutionalization of co-responsibility requires a governance which goes beyond self-regulating mechanisms within science itself. There is a ‘responsibility’ for ‘organizing co-responsibility,’ shared by scientific, policy and societal actors. The institutionalization of this responsibility will have consequences for the way science is funded and organized, for example through policy and financial incentives to embark on socially relevant open research missions. For example, by means of co-creation and co-design of research agendas with scientific, policy and societal actors which are currently foreseen in the “Horizon Europe (2021-2027)” program. An important aspect is the governance of the research missions themselves. When open research missions are conducted to achieve a socially desirable objective, its governance and organization will significantly have to differ from research missions with a primary technological objective (for example: ‘putting a man on the moon’). In fact, the ultimate step to complete RRI with anticipatory governance is inherent for this type of mission-oriented research.

The governance of research of innovation based on a Framework of RRI thus requires credible research, open and responsive research and responsible research that anticipates socially desirable outcomes. This anticipation also presupposes that such research and innovation is inevitably value-driven as those values mark the desirability or undesirability of research and innovation outcomes.

The desirability of open scholarship is often motivated by the wish to achieve better scientific practices. However, RRI is more ambitious and represents an effort to drive research and innovation towards socially desirable outcomes. We, therefore, must address the question how we can define these outcomes, for example by the way we anticipate them. The employment of foresight is one of the few tools we have at our disposal, and possibly the most robust one. Broadly speaking, anticipation can be defined as an activity characterized by the use of the future (or futures) to guide and orient decision making in the present. Anticipation must therefore be distinguished from forecasting.

The question of socio-technical futures is critical in this context because the ways in which scientific and technological practices are articulated derive from the anticipatory capacity, that is to say, from the capacity to promote certain research and innovation trajectories in the present on the basis of visions and expectations regarding future promises. Therefore, anticipatory responsibility goes beyond the traditional tendency to approach responsibility as a mere regulatory exercise; an exercise in which the socio-economic justification of scientific or technological innovations is not problematized, on the basis of future promises linked to them. This activity of futures building opens the door to publics. Anticipatory governance is an instrument for the engagement of publics in the exercise of opening science and innovation that should contribute to a more robust articulation of the relations between societal actors.

Anticipatory innovation processes are understood as open and deliberative processes, in which the values, motivations and expected benefits of innovations appear to be subject to public scrutiny. As such, the understanding of those anticipatory innovation processes emphasizes the need to critically and openly analyze the ways in which socio-economic and environmental challenges and their potential solutions are established. This implies recognizing anticipation as a fundamental component of responsible governance; a component that enables the construction of “socio-technical futures” as a guide for decision-making in the present. It is fundamental because anticipation becomes the component that modulates the degree of responsibility of responsible open scientific-technological practices. However, despite its central relevance, the meanings of anticipation and anticipatory governance are divers, often disparate, if not contradictory, as Mario Pansera showed in his presentation.

In this context of plurality of meanings, the risks of the very concept of anticipatory governance for the achievement of more responsible science and innovation should not be forgotten, as Alfred Nordman and others have shown. Not only because some anticipatory governance understandings close down the field of possible alternatives and courses of action. (We can call them closed anticipatory governance patterns.) The risks arise above all, however, because anticipatory governance is permanently connected to the risk of instrumentalisation by an innovation system highly committed to techno-industrial developmentalism and economic competitiveness. Therefore, its contribution to responsible science and innovation and its transformative potential should not be taken for granted. Attention needs to be paid to the way in which power relations and instrumentalisation dynamics characteristic of innovation systems tend to exclude, or to close down, the emergence of alternative ways of approaching scientific-technical co-creation. That’s why, among other things, the transformative potential of anticipation towards more responsible forms of scientific practice has to remain analyzed and explored.

Reference

All European Academies (2017), The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity: https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/

Burgelman J-C, Pascu C, Szkuta K, Von Schomberg R, Karalopoulos A, Repanas K and Schouppe M (2019), Open Science, Open Data, and Open Scholarship: European Policies to Make Science Fit for the Twenty-First Century. Front. Big Data 2:43.

Merton, Robert K. 1979 [1942]. “The Normative Structure of Science.” In The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Von Schomberg, R (2019), Why responsible innovation in: R. Von Schomberg and J. Hankins (eds) International Handbook on Responsible Innovation: A Global Resource. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 12–32.

Rene runs a blog with free downloadable resources on RRI: https://Renevonschomberg.wordpress.com

proposed citation: René von Schomberg and Andoni Ibarra (2022). Introduction to the concepts of Open Science, Responsible Research and Innovation and Anticipatory Governance. https://khk.rwth-aachen.de/2022/07/25/3892/3892/