ELISABETH RÖHRLICH

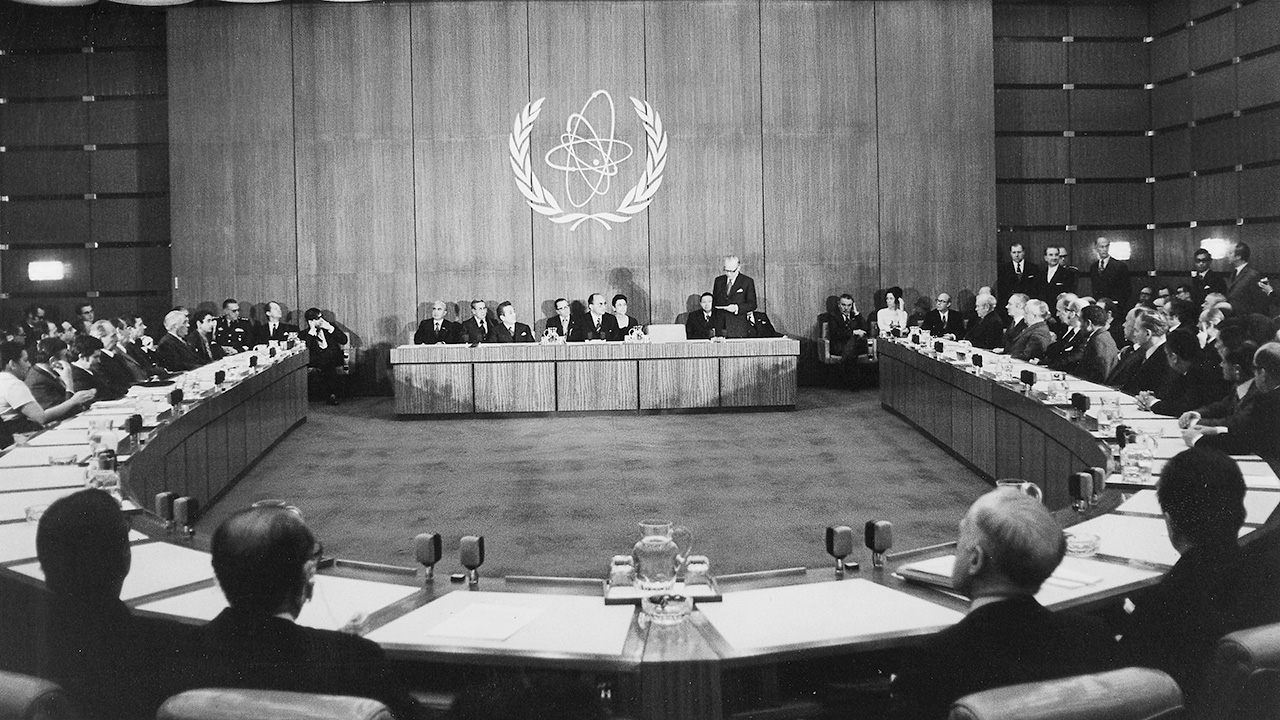

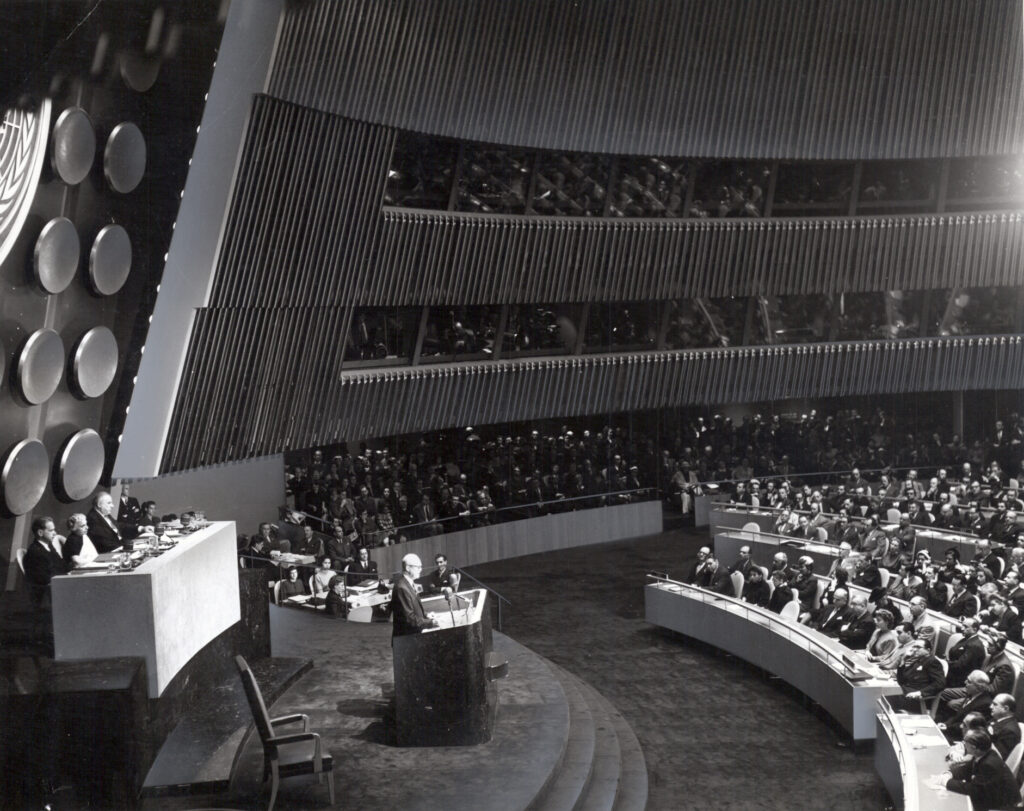

Artificial intelligence (AI) seems to be the epitome of the future. Yet the current debate about the global regulation of AI is full of references to the past. In his May 2023 testimony before the US Senate, Sam Altman, the CEO of Open AI, named the successful creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) a historical precedent for technology regulation. The IAEA was established in 1957, during a tense phase of the Cold War.

Calls for global AI governance have increased after the 2022 launch of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s text-generating AI chatbot. The rapid advancements in deep learning techniques evoke high expectations in the future uses of AI, but they also provoke concerns about the risks inherent in its uncontrolled growth. Next to very specific dangers—such as the misuse of large-language models for voter manipulation—a more general concern about AI as an existential threat—comparable to the advent of nuclear weapons and the Cold War nuclear arms race—is part of the debate.

Elisabeth Röhrlich

Elisabeth Röhrlich is an Associate Professor at the Department of History, University of Vienna, Austria. Her work focuses on the history of international organizations and global governance during the Cold War and after, particularly on the history of nuclear nonproliferation and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

From nukes to neural networks

As a historian of international relations and global governance, the dynamics of the current debate about AI regulation caught my attention. As a historian of the nuclear age, I was curious. Are we witnessing AI’s “Oppenheimer moment,” as some have suggested? Policymakers, experts, and journalists who compare the current state of AI with that of nuclear technology in the 1940s suggest that AI has a similar dual use potential for beneficial and harmful applications—and that we are at a similarly critical moment in history.

Some prominent voices have emphasized analogies between the threats posed by artificial intelligence and nuclear technologies. Hundreds of AI and policy experts signed a Statement on AI Risk that put the control of artificial intelligence on a level with the prevention of nuclear war. Sociologists, philosophers, political scientists, STS scholars, and other experts are grappling with the question of how to develop global instruments for the regulation of AI and have used nuclear and other analogies to inform the debate.

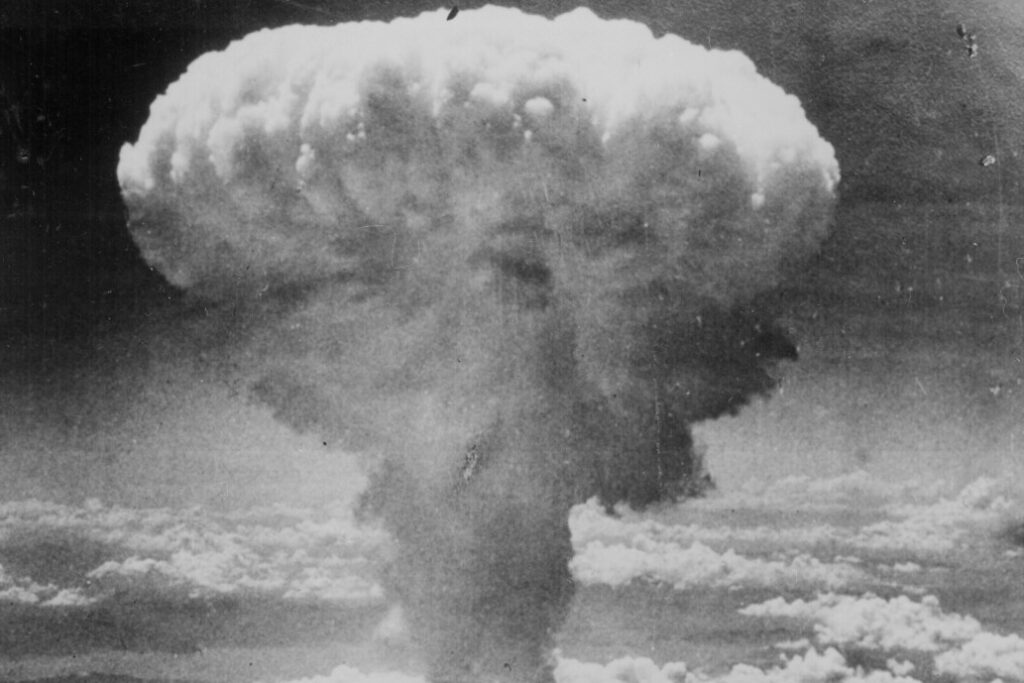

There are popular counterarguments to the analogy. When the foundations of today’s global nuclear order were laid in the mid-1950s, risky nuclear technologies were largely in states’ hands, while today’s development of AI is driven much more by industry. Others have argued that there is “no hard scientific evidence of an existential and catastrophic risk posed by AI” that is comparable to the threat of nuclear weapons. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 had drastically demonstrated the horrors of nuclear war. There is no similar testimony for the potential existential threats of AI. However, the narrative that because of the shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki world leaders were convinced that they needed to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons is too simple.

Don’t expect too much from simple analogies

At a time of competing visions for the global regulation of artificial intelligence—the world’s first AI act, the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, just entered into force in August 2024—a broad and interdisciplinary dialog on the issue seems to be critical. In this interdisciplinary dialog, history can help us understand the complex dynamics of global governance and scrutinize simple analogies. Historical analysis can place the current quest for AI governance in the long history of international technology regulation that goes back to the 19th century. In 1865, the International Telegraph Union was founded in Paris: the new technology demanded cross-border agreements. Since then, any major technology innovation spurred calls for new international laws and organizations—from civil aviation to outer space, from stem cell technologies to the internet.

For the founders of the global nuclear order, the prospect of nuclear energy looked just as uncertain as the future of AI appears to policymakers today. Several protagonists of the early nuclear age believed that they could not prevent the global spread of nuclear weapons anyway. After the end of World War II, it took over a decade to build the first international nuclear authority.

In my recent book Inspectors for Peace: A History of the International Atomic Energy Agency, I followed the IAEA’s evolution from its creation to its more recent past. As the history of the IAEA’s creation shows, building technology regulation is never just about managing risks, it is also about claiming leadership in a certain field. In the early nuclear age—just as today with AI—national, regional, and international actors competed in laying out the rules for nuclear governance. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented his 1953 proposal to create the IAEA—the famous “Atoms for Peace” initiative—as an effort to share civilian nuclear technology and preventing the global spread of nuclear weapons. But at the same time, it was an attempt to legitimize the development of nuclear technologies despite its risks, to divert public attention from the military to the peaceful atom, and to shape the new emerging world order.

Simple historical analogies tend to underestimate the complexity of global governance. Take for instance the argument that there are hard lines between the peaceful and the dangerous uses of nuclear technology, while such clear lines are missing for AI. Historically, most nuclear proliferation crises centered around opposing views of where the line is. The thresholds between harmful and beneficial uses do not simply come with a certain technology, they are the result of complex political, legal, and technical negotiations and learnings. The development of the nuclear nonproliferation regime shows that not the most fool-proof instruments were implemented, but those that states (or other involved actors) were willing to agree on.

History offers lessons, but does not provide blueprints

Nuclear history offers more differentiated lessons about global governance than the focus on the pros and cons of the nuclear-AI analogy suggests. Historical analysis can help us understand the complex conditions of building global governance in times of uncertainty. It reminds us that the global order and its instruments are in continuous process and that technology governance competes with (or supports) other policy goals. If we compare nuclear energy and artificial intelligence to inform the debate about AI governance, we should avoid ahistorical juxtapositions.